COVID-19’s devastating toll: An increase in adolescent suicides and mental health crises

The past decade has seen worrisome increases in self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among adolescents. Two new studies from Boston Children’s Hospital show that the situation became even more acute with the onset of COVID-19.

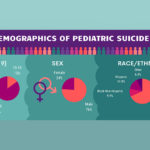

Epidemiologist Maimuna Majumder, PhD, and colleagues at the Computational Health Informatics Program (CHIP) at Boston Children’s partnered with public health departments in 14 U.S. states to gather data on suicide. As they report in JAMA Pediatrics, 10- to 19-year-olds accounted a greater share of total suicides in 2020 than in prior years. Their share increased from 5.9 percent from 2015-2019 to 6.5 percent in 2020, a statistically significant rise of 10 percent. The team is now finalizing an expanded analysis covering all 50 states.

A hospital snapshot

Patricia Ibeziako, MD, associate chief of clinical services in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Services at Boston Children’s, saw a similar trend when she and her colleagues looked back at the hospital’s own records. Their findings appear in Hospital Pediatrics, a journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

During the two-year study period — spanning the first pandemic year and the year just prior — nearly 3,800 children ages 4 to 18 were admitted to the emergency department (ED) or inpatient units for mental health-related reasons. About 80 percent were adolescents ages 12 to 18.

In the year before the pandemic, 50 percent of admitted patients had suicidal ideation or had made suicide attempts. That jumped to 60 percent during the first pandemic year (March 2020 to February 2021). The proportion making actual suicide attempts rose from 12 to 21 percent of admissions.

“The majority of suicide attempts were overdoses,” says Ibeziako. “We were seeing patients without known mental health issues presenting for the first time with suicide attempts, as well as patients with pre-existing mental health diagnoses.”

An influx of adolescents in crisis

Aside from suicidality, mental health admissions at Boston Children’s increased year over year for depressive disorders (from 63 to 70 percent of admissions), anxiety disorders (from 46 to 51 percent), eating disorders (from 7 to 14 percent), substance-related disorders (7 to 9 percent), and obsessive-compulsive related disorders (4 to 6 percent). (Many patients had more than one diagnosis.) Girls were especially affected: Their share of mental health admissions increased from 56 to 66 percent.

“Boarding” — caring for patients in the ED or in an inpatient unit while waiting for a psychiatric placement — increased dramatically during the first pandemic year. Fifty percent of patients boarded for two or more days, versus 30 percent the prior year; the average boarding time rose from 2.1 to 4.6 days. Boston Children’s wasn’t alone in this. In a March 2021 survey of 88 U.S. hospitals, 99 percent were boarding youth awaiting psychiatric placement.

“While boarding keeps patients safe, it is an inherently stressful process associated with a lot of uncertainty, anxiety, and unpredictability for families,” says Ibeziako.

A perfect storm

COVID-19 has clearly exacerbated a perfect storm, says Ibeziako. It has also exposed major deficiencies in our pediatric mental health care system and a growing crisis that isn’t going away.

“The increase in suicidal behavior among youth very much predates the pandemic,” she says. “The pandemic did not alter this trend — it simply amplified it.”

At a time when adolescents should be socializing and gaining independence, remote learning made them even more sedentary, more socially isolated, and more glued to screens. Add to that the stress COVID-19 placed on many families, loss of caregivers to the pandemic, cancellation or disruption of sports, proms, and graduation ceremonies, and increasing climate anxiety.

But the most common risk factor for adolescents has continued to be academic pressure: homework, making good grades, getting into college. “For years, school pressure has been the number-one stressor reported by adolescents presenting to the hospital in mental health crisis,” Ibeziako says. “We see a significant drop during the summer months when kids are out of school.”

An advocacy agenda for mental health

Boston Children’s has been seeking to stem the tide in several ways. The Boston Children’s Hospital Neighborhood Partnerships program provides consultation, training, and early intervention services to promote the mental health and well-being of students in the Boston Public Schools. The hospital has also expanded its outpatient mental health services at its main campus and Boston Children’s Waltham. Waltham also houses a second inpatient psychiatry unit and the less-intensive residential Community Based Acute Treatment program. Finally, Boston Children’s seeks to further expand its behavioral health services through a recent affiliation agreement with Franciscan Children’s.

On the policy level, Boston Children’s has joined the Sound the Alarm for Kids campaign, together with the Children’s Hospital Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, to urge passage of H.R. 7236: Strengthen Kids’ Mental Health Now by the U.S. House of Representatives. Introduced in March, H.R. 7236 would boost investment in the nation’s pediatric mental health infrastructure. A companion U.S. Senate bill is in the works.

In Massachusetts, through the Children’s Mental Health Campaign, Boston Children’s is advocating for S.2584: An Act Addressing Barriers to Care for Mental Health. It unanimously passed the Senate last fall but a House version is still pending.

“We have to address the decades-old underinvestment in mental health services,” says Ibeziako. “This effort has to be multi-pronged, at every level of care: school mental health services, integration of behavioral health in primary care, outpatient services, and intensive inpatient and partial hospitalization services. As a society, we need to address the growing pressures and expectations on our youth, from school curricula to the role of technology.”

Watch the recent webinar, Children’s Behavioral Health Crisis: The Time Is Now, from Boston Children’s Office of Government Relations and the Children’s Mental Health Campaign.

Related Posts :

-

Suicide prevention in teens: Can we intervene through primary care?

The past year has seen a disturbing rise in suicidal thoughts and attempts among adolescents, with a spike of suicidal ...

-

Poverty associated with suicide risk in children and adolescents

Suicide in children under age 20 has been increasing in the U.S., with rates almost doubling over the last decade. ...

-

The adolescent mental health crisis: Bolstering primary care capabilities

The mental health crisis among children and teens shows no sign of abating, and COVID-19 has clearly made matters worse. ...

-

When a friend dies by suicide: Preventing suicide contagion

Suicide can shake an entire community. For some kids, a friend or classmate’s suicide increases the risk that they ...