Eight years of preparation for a surgical first: a partial heart transplant

Boston Children’s cardiac surgeons have an overriding goal for each patient: If possible, repair their congenital heart defect (CHD) — rather than replace any native heart tissue. Preserving heart tissue often leads to a speedier and more complete recovery and longer-lasting cardiac function.

Sometimes, though, a patient’s valve tissue is beyond repair and a bioprosthetic or mechanical replacement valve are the only other options. That is, those were the only other options until May, when the surgery team introduced a new one. Sitaram Emani, MD, and colleagues performed a partial heart transplant on a 4-year-old boy, implanting a donor’s aortic valve. “I see this opening a door for the treatment of conditions that don’t have ideal solutions,” Emani says.

The patient, Jack Mangan, is “doing wonderful and has more energy than before,” Emani says. The partial heart transplant is the first in New England and, based on its success, probably the first of many at Boston Children’s.

“Every patient needs to be looked at individually,” says Christopher Baird, MD, a cardiac surgeon and director of the Congenital Heart Valve Program. “We always first consider repair or reconstruction of a diseased valve, but some patients need a replacement valve — either tissue or mechanical. We can do that through several procedures, including the Ross procedure and now a partial heart transplant, which both replace a diseased valve with healthy valve tissue that will grow. It comes down to whatever is the best option for a patient.”

Running out of treatment options

Jack had aortic valve stenosis. Despite two fetal cardiac interventions that prevented him from potentially developing hypoplastic left heart syndrome and then surgical valve repairs in his first year of life, he still had residual aortic valve disease. “That’s the reality of aortic valve surgery for infants and young children,” says one of his cardiologists, Matan Setton, MD. “Even with a perfect operation, it can have limited longevity or durability.”

Emani tried to make the aortic valve bigger and open more easily by removing some tissue, but there was residual stenosis; the left ventricle would continue to need to work harder to supply blood to the body. Jack’s care team decided he needed a new aortic valve after considering how he’d already had several operations and how myocardial scarring was elevating the filling pressures in his left ventricle.

The team briefly considered the Ross procedure, a last-option treatment that moves a patient’s pulmonary valve into the position of the diseased aortic valve, which is removed. The new aortic valve grows with a child, but a drawback for some families is that a donated pulmonary valve that replaces the moved one eventually needs to be replaced.

Knowing that Jack’s parents, Amy and Chris, wanted to limit future operations as much as possible, his care team introduced the idea of a partial heart transplant. They advised that even though early results show that a partial heart transplant appears to be effective and safe, it is a new procedure. There could still be complications and a chance, no matter how remote, that further operations might be needed. “It still seemed like the most durable option,” Amy says. “We said, ‘Let’s do it. Let’s take this on together as a team.’ Now, Jack’s heart is as healthy as it has ever been, so we’re extremely grateful.”

A heart donor’s gift of a healthy aortic valve

A partial heart transplant replaces a diseased valve with a healthy valve from a donor. The cardiac surgery team established protocols for a partial heart transplant eight years ago but didn’t have an ideal patient until Jack. Duke University Hospital performed the world’s first partial transplant in 2022 and a few other heart centers have since followed.

Jack and his parents, who live in New Jersey, drove to Boston as soon as a donor match was found. The Benderson Family Heart Center — cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, nurses, the Cardiovascular 3D Modeling and Simulation team, and cardiac imaging specialists — was ready for the moment.

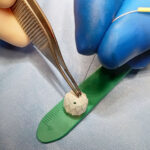

“The donor heart muscle wasn’t working well, so we weren’t going to use it,” Emani recalls. “But the valves were working great.” Operating through the night and into the next day, Emani and his surgery colleagues removed the aortic valve from the donor heart and placed it in the spot opened by the removal of Jack’s own valve. His coronary arteries were then attached to the aorta.

“This was a unique opportunity for us to use that donor’s gift,” Emani says. The partial transplant appears to be the first on a patient who wasn’t critically ill but rather as an option to another procedure, he says.

Reducing medication and watching for tissue growth

While recipients of new hearts require some level of immunosuppressant medication for the rest of their lives, patients of partial heart transplants should require a lesser amount of immunosuppressives for several months after the procedure.

Jack is receiving a full dosage now to ensure his body doesn’t reject the new aortic valve, but his care team’s aim is to gradually reduce the medication. They feel confident with this approach, based on outside studies and catheter biopsies they performed on patients’ transplanted hearts that showed even when immune suppression was not sufficient and their bodies were rejecting a new heart, valve function remained normal, says Tajinder (TP) Singh, MD, MSc, a cardiologist who leads Jack’s recovery care team.

Just as importantly, they hope the new aortic valve will grow along with Jack, whose procedure is part of a clinical trial that will review valve growth over the next few years. (Data from Duke University’s first procedure show that a replacement valve and arteries grew along with their patient, who was a newborn during surgery.) “The idea is that with live tissue, the ring of the valve should grow along with the child,” Singh says.

Hope for Jack and others who need a new valve

Emani and the cardiologists envision the partial heart transplant becoming a viable option for patients whose heart valves are beyond repair. “This is something that has the promise to last for years, if not a decade or longer,” Setton says. And the procedure doesn’t have to be limited to aortic valves. The cardiac surgery team is now reviewing the feasibility of replacing a diseased mitral valve with a donor’s healthy one.

Making the case for a new standard

Boston Children’s Sitaram Emani, MD, other cardiac surgeons, and the president of New England Donor Services are advocating that heart valves donated for a partial heart transplant could be treated as organs, and not as tissue, so the process can meet clinical and ethical standards similar to what are applied to organ transplants.

Read their viewpoint in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“An Achilles heel of cardiac surgery is repair materials,” Emani says. “You have to find the right type of material to repair a valve or a pulmonary artery, and it doesn’t always work because you’re using dead tissue or artificial tissue. There’s tremendous benefit with this procedure because it’s living tissue. And a partial transplant is more ideal than a full transplant because the rest of a patient’s heart tissue is working; there’s no need to replace it. You just want to replace the parts that are dysfunctional, ideally with something that will grow over time.”

Jack is already showing signs of recovery. The transplanted aortic valve is functioning perfectly, Setton and Singh say, and his body has shown no signs of rejecting the donated tissue.

“He’s such a wonderful kid and so is his family,” Emani says. “We’re all excited he’s a pioneer for this. He’s the one trailblazing, so it was exciting to be part of that.”

Learn more about the Congenital Heart Valve Program or refer a patient.

Related Posts :

-

A heart valve that grows along with a child could reduce invasive surgeries

Clinical trials have started for the first prosthetic pulmonary valve replacement that is specifically designed for pediatric patients and can ...

-

Constant improvements make the Ross procedure a safe aortic valve replacement option

Cardiac surgeons understand that innovation isn’t always about invention. Improving something can be just as transformative. So it shouldn’...

-

Experience and innovation create a safer type of heart surgery

The Eureka moment came the day before heart surgery. Easton Schlein wasn’t an ideal candidate for a full-scale surgical ...

-

Finding a way to help newborns who can't immediately have heart treatment

Newborns with complex congenital heart defects (CHD) and pulmonary overcirculation often need treatment as soon as possible. Unfortunately, ...