The people and advancements behind 75 years of Boston Children’s Cardiology

Boston Children’s Department of Cardiology has more than 100 pediatric and adult cardiologists, over 40 clinical fellows learning the routines of heart care in a major hospital, 12 echocardiogram rooms dedicated to testing the function of a child’s heart, and five labs equipped to perform advanced catheterization procedures.

Many other numbers could highlight the dedication that the department has for treating children and adults with heart disease. But in 1949, that kind of assessment could consider only a single metric: one doctor.

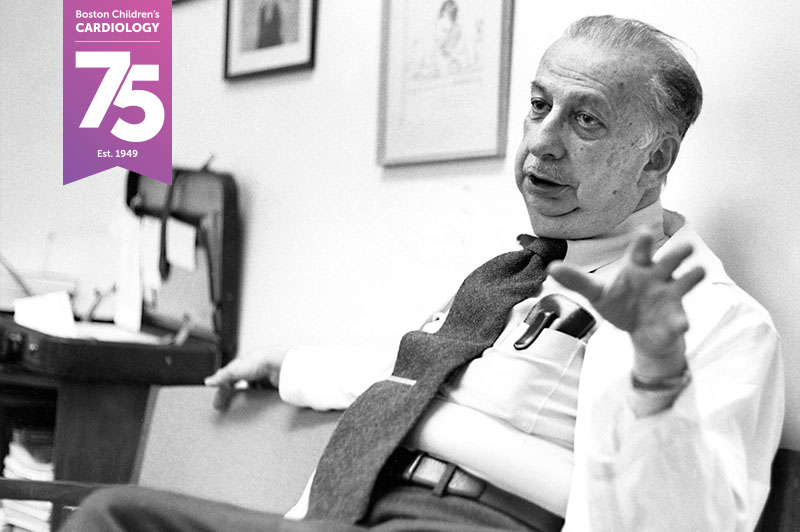

It was Dr. Alexander Nadas, the first cardiologist and really the first employee of a newly formed cardiology department. Dr. Nadas started work with one directive from his boss: develop a cardiac service for children comparable to the one for adults at what was then called Peter Bent Brigham Hospital.

Starting with Dr. Nadas, and carried on over the years by thousands of clinicians and support staff members, the department became one of the largest of its kind in the world. And on this, the 75th anniversary of its inception, the department is still considered a world leader in improving the lives of those with acquired and congenital heart disease. It’s a legacy that current Boston Children’s cardiologists fully appreciate.

“It’s an honor and privilege to be able to practice cardiology at Boston Children’s,” says Dr. Jane Newburger, who joined the department in 1976 as a fellow and is now Associate Chair for Academic Affairs. “It has never felt like a job to me.”

Going from bedrest to news-making surgery

Heart care at Boston Children’s actually started in 1918 with a clinic that diagnosed children who had heart disease or conditions that damaged the heart. But clinicians faced the limitations of medical technology, which prevented proper diagnosis and management. The only treatment they could offer was bedrest and a recommendation for children to not exercise or get their feet wet.

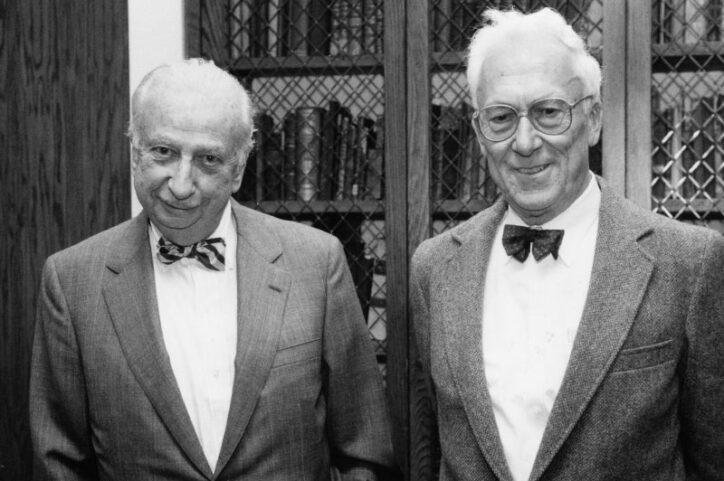

“There really was no formal pediatric cardiology in the country until the 1930s,” says Dr. Michael Freed, a Boston Children’s cardiologist who came to the hospital in 1970 as a fellow, eventually served as chief of cardiology inpatient services, and is still practicing.

Boston Children’s made international news in 1938 when Dr. Robert Gross performed the first surgical repair of a congenital heart defect (CHD) that, until then, had often caused early death. Still, even after that pioneering surgery, the hospital wasn’t fully focused on studying, diagnosing, and treating cardiovascular disease.

That changed in 1949. Boston Children’s physician-in-chief Dr. Charles Janeway decided the hospital had to take the lead in pediatric cardiology, Dr. Freed says. Dr. Janeway was motivated by the progress John Hopkins Hospital had made in diagnosing “blue” babies whose malformed hearts couldn’t distribute enough oxygen throughout the body. Dr. Janeway chose Dr. Nadas to lead a formal cardiology program that would work closely with a cardiac surgery program that informally began in 1938 with Dr. Gross’ surgery. “Boston Children’s was wise enough to recognize this was going be something that would make a difference,” Dr. Freed says.

Stretching the boundaries of heart care

The Department of Cardiology’s 75-year history can be viewed as two eras.

From the 1950s to 1980s, advancements came at a brisk pace. More doctors, nurses, and researchers came on board, and they embraced Nadas’ commitment to try new ways to improve pediatric cardiology. Innovations included adapting cardiac catheterization to safely diagnose and treat children and refining radiology to improve diagnoses and guide procedures such as angioplasty. Also, a program that focused on pulmonary function opened, and the study of exercise to measure children’s cardiac function became standard practice.

“I don’t think Dr. Nadas was highly mathematical or technical, but he had extraordinary emotional intelligence,” Dr. Newburger says. “He was a great judge of people’s abilities and their character. It was Dr. Nadas’s skill in building a team with complementary talents that fostered the growth of this great program.”

The next era, from the 1980s to today, brought far more advancements and at a more rapid pace. The development of electrophysiology, echocardiography, CT scans, and MRIs gave cardiologists a variety of perspectives to identify heart conditions. The establishment of the Cardiac Registry helped clinicians better understand congenital heart disease and enhanced the teaching of all anatomy and pathology. The evolution of the technologies and techniques that improved heart surgery — including anesthesia and mechanical support — contributed to an increase in precise and safe procedures. And procedures such as the first fetal cardiac intervention in the U.S. stretched the boundaries of possibility.

Those and many other steps forward have allowed cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to not only improve basic procedures but also make complex ones routine, says Dr. Stephen Sanders, who joined the department as a fellow in 1978, later led non-invasive cardiology, and is now co-director of the Cardiac Registry. “Those are all key elements that contribute to the quality outcomes we have here.”

It’s all about collaboration and self-improvement

Clinical care, research, and the training of future cardiologists can go only as far as the quality of the people on the cardiology staff, Drs. Freed, Newburger, and Sanders say.

“There is a unique combination of specialization and cooperation among the various parts of the department that probably doesn’t exist in many hospitals,” Dr. Sanders says. “Specialization is key to patient care, but you can’t be siloed. So the ability of people here to work together and make sure everything is aligned for patients — that’s what really makes this place terrific.”

Dr. Nadas, who retired in 1982, set a collaborative tone that has lasted until today, Dr. Freed says. “It gets harder to do that as you get bigger and bigger, but what makes it still work is the centrality of the patient. With the patient as the focus, the leadership of the department doesn’t expect you to do everything. It has encouraged everyone to have their areas of expertise and share their knowledge with other people in the department.”

Also, the ability of Dr. Nadas and Dr. Aldo Castaneda, who served as chief of Cardiac Surgery from 1972 to 1994, to unite cardiologists and cardiac surgeons is another legacy that still holds, the doctors say.

“In addition to being a good surgeon, Aldo’s real contribution was fostering self-criticism,” Dr. Sanders recalls. “I’d been in many Saturday morning conferences where he would say a surgery hadn’t gone the way he wanted, and he would take the blame. He worked out, in front of everyone, what he should have done and figured out how he could do it differently next time. He instilled that in his trainees and junior colleagues. So when we cardiologists made a mistake, people would be fighting in line to take the blame.”

A promising future will build on the past

Drs. Freed and Newburger say it’s difficult to call out one advancement or even several of them as being the most important to cardiology at Boston Children’s. Rather, each decade since 1949 brought new insights and innovations that worked well at the time but then led to more developments, each one building upon the one before it. “The changes have been remarkable,” Dr. Freed says.

What’s next? “Advances in heart regeneration and tissue engineering are going to be extraordinary. Maybe we’ll grow new heart valves, heart muscle, or even a whole new heart someday,” Dr. Newburger says. “We don’t yet know what great feats these technologies will bring.” Dr. Sanders points to how there are some CHDs — including heterotaxy and hypoplastic left heart syndrome — that are still difficult to treat. “There’s still room for advancement,” he says, “but we’re going to have to look at the molecular biology level of cardiac development and try to manage these CHDs in different ways.”

In the meantime, the doctors won’t hesitate to reminisce about why they and their colleagues have been motivated to thrive: the patients. “Caring for patients and their families is deeply gratifying. They become almost like family,” Dr. Newburger says. “It is such a great joy to see children with heart conditions grow up and for me to have been entrusted with helping guide critical decisions in their lives. Not a day goes by without my feeling the immense privilege and responsibility of pediatric cardiology practice.”

Learn more about the Department of Cardiology.

Related Posts :

-

Helping aspiring clinicians understand a virtual heart before they work with a real one

Jonathan Awori, MD, MS, MFA, isn’t embarrassed to say it took him a long time to completely understand the ...

-

Twenty years after a groundbreaking biventricular repair, Faith gives back by helping children with CHD

Faith Brackett doesn’t remember every detail of the time she was among the first children to have a new ...

-

Finding ways to reduce the financial and social costs of pacemakers

As the number of complex heart operations has increased over the years, so have cases of postoperative heart block, a ...

-

Research aims to pinpoint genetic connection between autism and heart disease

Cardiology and neurodevelopmental researchers have more questions than answers about the possible genetic links between congenital heart disease (CHD)&...