Opioid alternative? Taming tetrodotoxin for precise painkilling

Opioids remain a mainstay of treatment for chronic and surgical pain, despite their side effects and risk for addiction and overdose. While conventional local anesthetics block pain very effectively, they wear off quickly and can affect the heart and brain. Now, a study in rats offers up a possible alternative, involving an otherwise lethal pufferfish toxin.

In tiny amounts, in a slow-release formulation that efficiently penetrates nerves, the toxin provided a safe, highly targeted, long-lived nerve block, researchers report today in Nature Communications. The study was led by Daniel Kohane, MD, PhD, director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Kohane has long been interested in neurotoxins found in marine organisms like pufferfish and algae. In small amounts, they can potentially provide potent pain relief, blocking the sodium channels that conduct pain messages. Kohane’s lab has experimented with various ways of packaging and delivering these compounds in tiny particles, activating local drug release with ultrasound and near-infrared light, for example.

Taming a lethal toxin

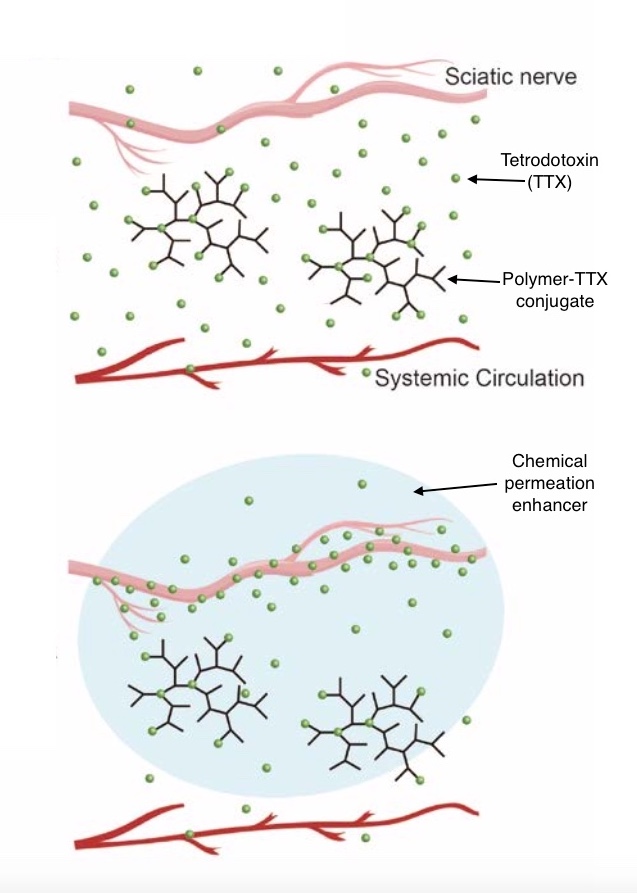

For the new study, the team chose tetrodotoxin, a potent, commercially available compound derived from pufferfish. (Tetrodotoxin is notorious for causing fugu poisoning from improperly prepared sashimi.) Rather than load it into particles as before, the team bound tetrodotoxin chemically to a polymer “backbone.” The body very slowly degrades the bond between tetrodotoxin and the polymer via hydrolysis, the natural breaking of chemical bonds by water). This releases the drug at a slow, safe rate.

“A lesson we learned is that with our previous delivery systems, the drug can leak out too quickly, leading to systemic toxicity,” says Kohane. “In this system, we gave an amount of tetrodotoxin intravenously that would be enough to kill a rat several times over if given in the unbound state, and the animals didn’t even seem to notice it.”

Kohane’s fellows, Chao Zhao, PhD, and Andong Liu, PhD, experimented with different drug loadings and different polymer formulations to get the longest-possible nerve block with the least toxicity.

“We can modulate the polymer composition to control the release rate,” Zhao explains.

Enhancing permeation

To further increase safety, the team paired the tetrodotoxin-polymer combination with a chemical penetration enhancer, a compound that made the nerve tissue more permeable. This allowed them to use smaller amounts of tetrodotoxin but still achieve nerve block.

“With the enhancer, drug concentrations that are ineffective become effective, without increasing systemic toxicity,” says Kohane. “Each bit of drug you put in packs the most punch possible.”

“We show that both the penetration enhancer and the reversible bonding of toxin to polymer are crucial to achieving such prolonged anesthesia,” adds Liu.

Good early results

When the researchers injected the combination near the sciatic nerve in rats, they achieved a nerve block for up to three days, with minimal local or systemic toxicity and no apparent sign of tissue injury.

In theory, nerve block in humans could last even longer, since one could administer it more safely than in rats, says Kohane. Using polymers with a longer retention time in tissue would also prolong effects.

“We could think about very long durations of nerve block for patients with cancer pain, for example,” he says. “Certainly for days, and maybe for weeks.”

Zhao and Liu were co-first authors on the Nature Communications paper. Coauthors, all in the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, were Claudia Santamaria, Andre Shomorony, Tianjiao Ji, Tuo Wei, Akiva Gordon, Hannes Elofsson, Manisha Mehta, and Rong Yang. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R35 GM131728).

The investigators together with Boston Children’s Hospital have applied for a patent covering the technology.

For information on licensing, contact Jennifer.Chou@childrens.harvard.edu in Boston Children’s Technology and Innovation Development Office.

Related Posts :

-

How a meniscal transplant made me a Boston sports fan

I was in kindergarten when my knee started popping and cracking. My parents and I didn’t know it at ...

-

Hard and beautiful at the same time: Five lessons of raising a medically complex child

When they learned they were expecting a baby, Michelle and Stephen Strickland were delighted. The South Carolina couple looked forward ...

-

‘Challenge accepted’: Sophia takes on a brain tumor

In 2023, Sophia Mordini landed the role of a lifetime. A competitive dancer, the 12-year-old would play Clara in her company’...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...