Bringing the Ozaki procedure to the world to repair children’s aortic valves

Children with aortic stenosis or regurgitation often need surgery to reconstruct or replace the aortic valve. However, existing bioprosthetics can fail over time, and mechanical leaflets and valves require lifelong anticoagulant therapy. Christopher Baird, MD, director of the Congenital Heart Valve Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, saw a promising alternative emerge in adult cardiac surgery: aortic valve neo-cuspidization, also known as the Ozaki procedure.

Developed by Japanese heart surgeon Shigeyuki Ozaki, PhD, in 2007, the operation reconstructs valves with tissue from the patient’s pericardial sac. The newly crafted valves behave much like real heart valves, allowing more normal blood flow through the aorta.

The Heart Center began offering the procedure in 2015, after Baird performed the first two pediatric cases under Ozaki’s tutelage. Short-term pediatric results have been promising. Baird, Brenda Cooney, MSHS, PA-C, and other colleagues have since been training cardiac surgical and ICU teams in the U.S. and around the world for several years.

“These trainings evolved out of our travels with the International Quality Improvement Collaborative (IQ/IC) for Congenital Heart Disease, which provides a benchmark for congenital cardiac surgery in low and middle income countries,” says Cooney. “With limited solutions for pediatric aortic valve disease, many centers became very interested in our experience with the Ozaki procedure and requested our help in training.”

Standardizing a complex heart operation

The pediatric Ozaki procedure is an attractive option for low- or middle-income countries that have difficulty accessing expensive prosthetic or mechanical valves for children with valve disease, says Cooney.

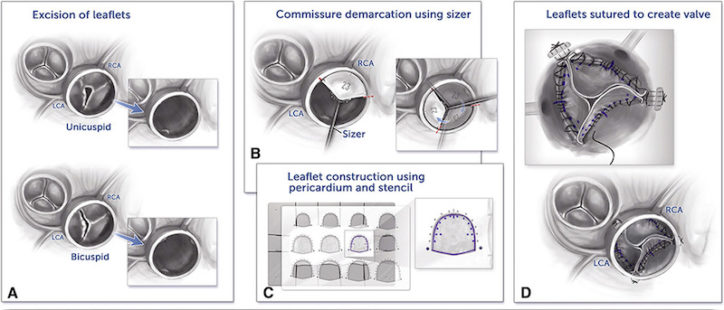

The technique employs custom sizers to measure the child’s aortic root and a template placed over the pericardial tissue, from which valve leaflets of the appropriate size are cut. After excising the patient’s existing leaflets, the surgeon sutures the newly fashioned leaflets into the annulus to reconstruct the valve.

“The procedure is technically more challenging in children,” Baird says. “The aortic root and annulus are much smaller, and it’s harder to align the corners. But once you standardize that, it becomes easier.”

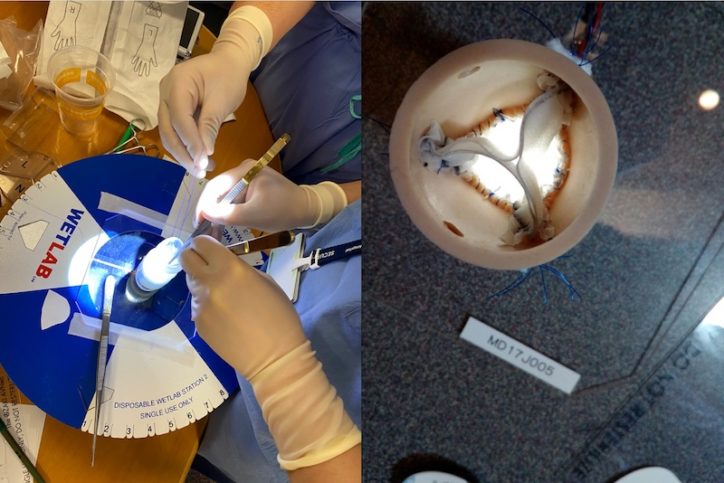

The training sessions use a benchtop model of the aortic root, with ridges to represent the native annulus, and sheets of synthetic material for crafting the leaflets. These as well as the sizers and template, are commercially sourced from Japan. Smaller versions have been created specifically for pediatric use.

While some training sessions have been conducted via Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic, Baird and Cooney say there’s no substitute for live, hands-on learning.

“There are many subtleties to sewing in the leaflets that only hands-on experience can teach,” says Cooney.

The Ozaki Global Registry

Trained by Baird and Cooney, surgeons in Chile, China, Vietnam, India, the Republic of Georgia, and Spain have begun doing their own pediatric Ozaki procedures. They are contributing outcomes data to a global registry launched by Boston Children’s about a year ago. In some cases, international fellows training at Boston Children’s have brought the procedure back to their home countries.

The hope is that Ozaki repairs will remain durable as children’s valves and aortic root grow. It appears that the new valves can accommodate a certain amount of growth while maintaining good leaflet coaptation. But there are no long-term data.

Ozaki procedures in other valves

While roughly 99 percent of Ozaki procedures at Boston Children’s have involved the aortic valve (typically 3-leaflet or single-leaflet replacement), Baird and colleagues have performed an adapted version for other valves such as the truncal valve, pulmonary valve, and right ventricle-to-pulmonary-artery conduits.

That’s where the Ozaki Global Registry comes in. Baird is medical principal investigator, and Lynn Sleeper, ScD, is principal investigator of its Data Coordinating Center, housed in the Heart Center. The Registry is sponsored in part by the Japanese Organization for Medical Device Development, Inc.

“We are collecting surgical and medical history information on each child and adult, along with annual clinical and echocardiographic data to learn about the procedure’s longevity for aortic valve reconstruction,” Sleeper says.

Outcomes tracked include echocardiography measures of aortic regurgitation and aortic stenosis, the need for repeat operations, the need for pacemakers, transplant, and death. As of July 26, the registry had more than 250 cases, 130 of them pediatric, with 10 centers participating worldwide. (Hospitals interested in joining can complete this form.)

The registry is expanding as more centers get training. “International work is very rewarding,” says Cooney. “The clinical teams are eager to learn anything possible to help these children.”

One fond memory was a trip to Vietnam, where Cooney and Baird performed the Ozaki procedure on four young girls alongside the Vietnamese surgeons. “The next year, they surprised us by bringing the girls back to say thank you for repairing their aortic valves,” Cooney says. “There was not a dry eye in the house. That’s what makes these trips worthwhile.”

Refer a patient to the Congenital Heart Valve Program

Related Posts :

-

Inspired by Chinese finger traps, an annuloplasty ring that grows with the child

This post is part of a series on innovations to treat valvular disease in children. Read our prior posts on ...

-

Someday, this prosthetic heart valve might be the only one a child needs

More than 330,000 children worldwide are born with a heart valve defect, and millions of others develop rheumatic heart disease requiring ...

-

Innovations in transcatheter valve replacement

The Cardiac Catheterization Program at Boston Children’s Hospital has been at the cutting edge of pediatric care for more ...

-

BACH Program: Heart care for patients of all ages

At 73, Fran Sansalone might not seem like a typical Boston Children’s Hospital patient. But she’s one of a ...