Tau protein changes correlate with Alzheimer’s disease dementia stage

Research into Alzheimer’s disease has long focused on understanding the role of two key proteins, beta amyloid and the tau protein. Found in tangles in patients’ brain tissue, a pathological form of the tau protein contributes to propagating the disease in the brain.

Key takeaways

- A pathological form of the tau protein contributes to the progression of disease in Alzheimer’s disease.

- The tau protein changes over time during the course of disease, a result of chemical modifications.

- Researchers found that chemical modifications to tau correlate with disease severity.

- Looking forward, multiple Alzheimer’s drugs may be needed, each targeting the unique chemical modifications on tau protein at different stages of illness.

In new research from their joint laboratory, Judith Steen, PhD, and Hanno Steen, PhD, show for the first time that this pathological tau protein changes its forms over time, which could mean it will take multiple drugs to target it effectively.

For years, pharmaceutical companies have largely focused with very limited success on developing Alzheimer’s drugs against beta amyloid. More recently, drug discovery has shifted to drugs against tau. This new tau discovery may help prevent the same fate for drugs now in development against tau because it shows that the protein may present with one set of targets at early stages, with other targets at later stages in the disease process.

“The tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease looks different at every stage,” says lead investigator Judith Steen. “We discovered that tau undergoes a series of chemical modifications in a stepwise process that correlates with disease severity. This suggests that we need to have different diagnostics and treatments for every stage of disease.”

Published in a paper in Cell, this research represents years of work in the Steen lab funded by the Tau Consortium. Its mission is to accelerate discoveries of new treatments for Alzheimer’s and other disease related to “tauopathies” — abnormalities of the tau protein.

Tau changes according to dementia stage

The Steen lab team looked at tau aggregates in tissues of two areas of the human brain, the frontal gyrus and the angular gyrus, from 49 patients with AD and 42 age-matched individuals without known Alzheimer’s or dementia. They found that the chemistry of the tau protein changed in Alzheimer’s patients. The tau had several modifications not found on normal tau, known as post-translational chemical modifications or PTMs. The specific chemically modified forms of tau correlated with dementia stage.

Stepwise chemical modifications

As we age, tau tangles accumulate in our brains, even if we don’t develop dementia. “But these aggregates are not as abundant and don’t look like the tau aggregates in patients who have severe Alzheimer’s disease,” says Steen. She believes that tau undergoes chemical changes after it’s first made in the body. Their team revealed 95 PTMs of the tau protein; about one-third of them were not described before.

“Chemical processing by a variety of enzymes introduces modifications to the original tau protein,” says Steen. Examples included addition of phosphate, methyl, acetyl, and ubiquitin groups, and others. The first step of disease appears to start with adding phosphate, with other changes following in a step-wise process. “We were able to see precisely what those modifications were, the extent of the changes, and we also could map it to a precise area of the tau protein,” Steen says.

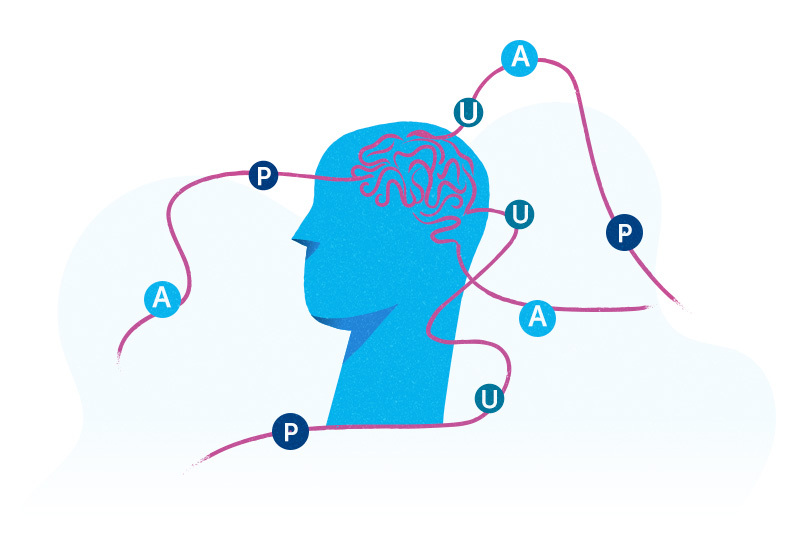

FLEXITau technology platform

Key to the study was use of a novel mass spectrometry technique developed within the lab to measure proteins. Called FLEXITau, and first described in a paper in 2016, it can sequence and quantify tau’s makeup with unprecedented accuracy. FLEXITau utilizes biochemistry, mass spectrometry and data analysis to provide information on chemical modifications of tau in brain tissue.

The Steen lab leveraged the platform to study brain tissues collected by NIH-funded brain banks from patients with neurodegenerative diseases, using it to analyze thousands of proteins from these tissues.

The FLEXITau approach provides a deeper understanding of tau pathology that the team believes may lead to novel therapeutics. It may also be useful for developing better diagnostic tools to identify biomarkers of Alzheimer’s and other tau-associated diseases.

More than one drug likely needed

The team’s discovery has immediate implications for the future of Alzheimer’s treatment.

“It is likely that to successfully target tau protein with an antibody or small molecule, you may need more than one to clear it,” explains Steen. “Early intervention may need different therapeutics compared with late stage Alzheimer’s because of the distinct PTM profiles associated with each stage of disease.”

The team is hopeful that exploring some these crucial chemical modifications may help explain how Alzheimer’s develops and progresses as well as further reveal the chemistry of the tau protein in its earliest stages.

Other members of the core team contributing to this research include co-first authors Hendrik Wesseling and Waltraud Mair, Mukesh Kumar, and Christoph N. Schlaffner. Additional contributions were made by Shaojun Tang, Pieter Beerepoot, Shuko Takeda, Simon Dujardin, Peter Davies, Kenneth S Kosik, Bruce L. Miller, Sabina Berretta, John C. Hedreen, Lea T. Grinberg, William W. Seeley, and Bradley T. Hyman.

The project was funded by the Tau Consortium, a research initiative conceived by the Rainwater family.

Learn more about research at Boston Children’s

Related Posts :

-

Targeting synapse loss in Alzheimer’s to preserve cognition — before plaques appear

Currently, there are five FDA-approved drugs for Alzheimer’s disease, but these only boost cognition temporarily and don’t ...

-

First sharp images reveal structure of key inflammatory protein

After decades of attempts by the scientific community, researchers have now provided the first clear look at a protein implicated ...

-

The thalamus: A potential therapeutic target for neurodevelopmental disorders

Years ago, as a neurology resident, Chinfei Chen, MD, PhD, cared for a 20-year-old woman who had experienced a very ...

-

Could peripheral neuropathy be stopped before it starts?

An increase in high-fat, high-fructose foods in people’s diets has contributed to a dramatic increase in type 2 diabetes. This, ...