Children wait for new cancer drugs 6.5 years longer than adults

A 20-year analysis finds that FDA-approved cancer drugs took a median of 6.5 years to go from the first clinical trial in adults to the first trial in children. That’s not good enough for researchers at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, who are calling for expanding children’s access to experimental cancer therapies.

“It’s taking too long to even start studying these therapies in children,” says Steven G. DuBois, MD, director of experimental therapeutics at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s. “As a doctor taking care of young cancer patients, this is tremendously frustrating. If I were a parent of a child with cancer, I wouldn’t stand for this.”

In the May issue of the European Journal of Cancer, DuBois and colleagues systematically calculated the times from first-in-human to first-in-child trials of oncology drugs. They identified drugs approved by the FDA for any cancer indication from 1997 to 2017. Next, they searched clinical trials registry data, published literature, and abstracts presented at cancer meetings to find the relevant trials and start dates.

Lagging pediatric cancer drug trials

During the 20-year period, 126 drugs won initial FDA approval for an oncology indication. After the researchers excluded hormonal modulators, not relevant to children’s cancers, 117 agents remained for analysis. Of these, 15 drugs (12.8 percent) had not yet had a pediatric trial. And just six drugs (5.1 percent) included children in the initial FDA approval.

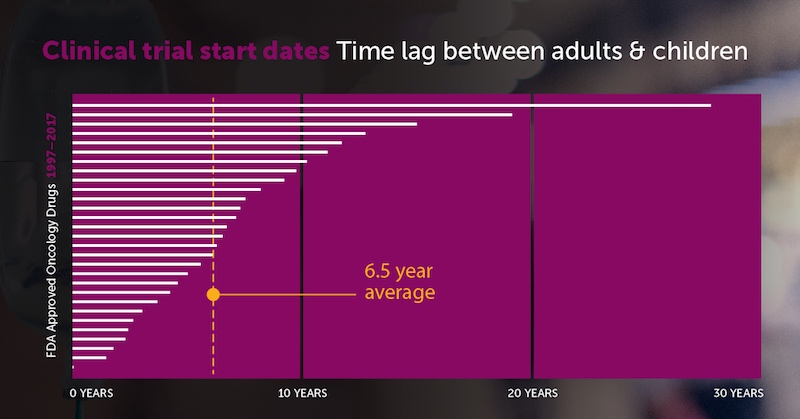

All told, there was a median 6.5-year lag between first-in-human and first-in-child clinical trials, with a range of 0 to 27.7 years:

Why do kids have to wait so long to take part in cancer drug trials? “Some may argue that the lag is appropriate to ensure the safety of a vulnerable pediatric population,” says DuBois. “Others may argue that this lag is too long for children with life-threatening diseases, and that some agents that fail in adult indications may prove to be important drugs for pediatric indications.”

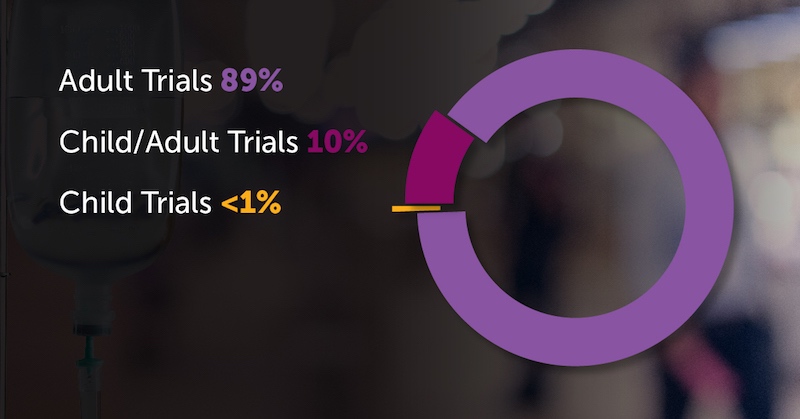

To understand children’s limited access to experimental therapies, look at the open Phase 1 trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov from 1998-2007:

The picture is similar for Phase 2 trials. But hopefully, these trends will start to reverse going forward. The recent U.S. RACE for Children Act strengthens the requirement that new cancer therapies with potential biological relevance to pediatric cancers be tested in children. This study can serve as a benchmark as this new policy is enacted, says DuBois.

DuBois is corresponding author on the paper. Dylan V. Neel, Harvard Medical School student, and David S. Shulman, MD, from Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s, were coauthors. The study was supported by Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Related Posts :

-

Promising advances in fetal therapy for vein of Galen malformation

In 2024, Megan Ingram* of California and her husband were preparing for the birth of their third child when a 34-week ...

-

A true hero’s journey: How a team approach helped Wolfie overcome pancreatitis

Wolfgang, affectionately known as “Wolfie,” is a bright and energetic 7-year-old with a quick wit and a love for making ...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, then a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity ...