Years in the making: Team performs successful fetal intervention for VOGM

On an ordinary Wednesday in March, a team of specialists from two institutions made the extraordinary happen: a first-of-its-kind intervention for a rare, life-threatening type of blood vessel anomaly called a vein of Galen malformation (VOGM) — performed in utero.

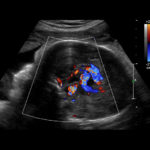

The ultrasound-guided embolization involves deploying tiny metal coils into the affected vein via a microcatheter inserted through a needle that is guided through the mother’s abdomen and into the fetus’s brain.

“This represents a totally different way to treat these malformations, both conceptually and technically,” says Darren Orbach, MD, PhD, chief of Neurointerventional Radiology at Boston Children’s Hospital and principal investigator for an ongoing clinical trial on the intervention.

A novel approach to VOGM

In this malformation, multiple arteries in the brain connect directly with a large central vein, instead of connecting with capillaries. This causes a rush of high-pressure blood into the vein that causes it to enlarge like a balloon and the rapid blood return to the heart can lead to pulmonary hypertension, brain injury, and congestive heart failure, often immediately after birth. If not diagnosed and treated early, VOGM can cause severe problems and may even be life threatening. About 60 percent of infants born with the condition develop these severe problems, often immediately after birth, and despite advances in embolization techniques in newborns, the mortality rate for those babies is roughly 40 percent.

Orbach, an internationally recognized expert in VOGM, has long been both fascinated and stymied by the complexity of the condition. In 2017, he began to seriously pursue a novel solution.

“I thought that if we could intervene before birth, we might be able to treat VOGM patients that we couldn’t otherwise help,” he says.

Preparation — then waiting

Drawing on lessons learned from advances in fetal cardiac interventions, Orbach worked closely with a core group of interdisciplinary specialists to conceptualize the procedure. The team included Wayne Tworetzky, MD, director of Boston Children’s Fetal Cardiology Program; Louise Wilkins-Haug, MD, PhD, division director of Maternal Fetal Medicine and Reproductive Genetics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Carol Benson, MD, former co-director of High Risk Obstetrical Ultrasound at Brigham and Women’s.

“It’s been a multi-hand, multi-specialty approach,” says Wilkins-Haug. “Everyone brings their own specific expertise.”

The project presented numerous technical challenges — namely, no one had ever accessed blood vessels in the fetal brain before. To determine the feasibility, the team worked with Boston Children’s Immersive Design Systems lab to create lifelike “phantom” models of the fetal brain and skull. This allowed them to practice a high-stakes procedure in a no-stakes environment, as well as ultimately to develop a protocol for a clinical trial.

The search for subjects proved equally challenging: Fetuses needed to have a VOGM that put them at high risk for acute heart failure after birth, but that had not yet injured their brain tissue. By February 2023, Orbach and his colleagues had FDA and IRB approval for a trial of 20 patients — but no eligible participants.

An ‘exhilarating’ improvement

Meanwhile, in Louisiana, Derek and Kenyatta Coleman were looking forward to growing their family of five. When an ultrasound at 30 weeks gestation revealed a large VOGM and enlarged heart, their local neurointerventional radiologist reached out to Orbach, who determined that the fetus could be an excellent candidate for prenatal intervention.

On March 15, Orbach, Wilkins-Haug, and Benson performed the procedure they had spent years planning. Using external pressure, Wilkins-Haug and her colleagues positioned the fetus so its head was facing Kenyatta’s abdominal wall. With ultrasound guidance by Benson, Wilkins-Haug introduced a needle through the uterus and into the back of the fetus’s skull. Once the tip of the needle was visible inside the large venous sinus in the head, Orbach — assisted by Boston Children’s endovascular neurosurgeon Alfred Pokmeng See, MD — inserted a microcatheter and microwire through the needle, navigated through the fetus’s venous sinus into the malformation, and deployed the embolization coils through the microcatheter.

The goal of the coils was to achieve significant blood flow reduction without completely blocking the VOGM. Although the team had planned to deploy 27 coils, the flow was diminished after 23 — an immediate improvement Orbach calls exhilarating.

Replicating success

Following a leak of amniotic fluid — a potential side effect of the procedure — clinicians delivered the infant two days later. Named Denver, she required no cardiovascular support or postnatal embolization, and her neurological status was normal; brain imaging shows that her brain is intact, with no hemorrhage or stroke. After gaining weight, she is now at home in Louisiana with her family, where she is monitored frequently by her local clinical team. Like all children with VOGM, she will undergo lifelong follow-up.

Denver’s case report was published in the May 4, 2023, issue of Stroke. The procedure “opens up doors for future fetal therapies,” says Orbach. “But it’s vitally important that we replicate the result in multiple patients. Getting the word out about our ongoing study — that’s our first order of business.”

Learn more about this fetal intervention or refer a patient to the MFCC.

Related Posts :

-

Fetal treatment for vein of Galen malformations

Vein of Galen malformations (VOGMs) are rare, life-threatening vascular malformations that often cause heart failure in neonates. The preferred postnatal ...

-

Changing the world: Baby Denver leads the way after first-of-its-kind procedure for VOGM

Denver Coleman is less than 2 months old, but she’s already helped blaze a trail for other children and families, ...

-

Treating a ‘unicorn’: Norman’s incredible journey with vein of Galen malformation

Norman Flores is near the top of his class at his Montessori preschool. He can recognize a Tesla just from ...

-

'To do what’s best for Marley': One family’s experience with a vein of Galen malformation

Last summer, Savannah and Brian were eagerly awaiting the birth of their first child. Savannah was scheduled to deliver their ...