An education in hemophilia for Colin’s new school

Every morning, one of Colin Bazinsky’s parents puts a needle into his chest to give him an infusion of clotting factor. You wouldn’t guess anything was amiss from the placid look on the 3-year-old’s face as he receives the infusion to treat his hemophilia. His state of calm reflects his parents’ matter-of-fact approach to the daily ritual that takes about an hour from start to finish. It also helps that Colin and his sister, Nora, associate infusions with screen time. “We’ve paired factor time with TV and now they both look forward to it,” explains their mother, Kate.

Colin was diagnosed with severe hemophilia A in 2017, when he was 16 months old. Hemophilia is a bleeding disorder that interferes with the body’s ability to form blood clots. Colin is missing blood clotting factor VIII. The treatment for his hemophilia, called “factor,” replaces the protein missing from his blood. Without factor, Colin would be at risk of spontaneous bleeding, severe bruising, permanent joint damage, possibly even death.

He started receiving daily infusions after Dr. Stacy Croteau discovered that his immune system was attacking the potentially life-saving medication, rendering it useless. Over time, the regular doses work in a similar manner as allergy shots, coaxing his immune system to stop treating the factor like a threat. As Colin’s body has learned to accept the treatment, he has started to get some protection, which means his parents don’t have to bring him to the emergency department every time he stumbles.

Weighing the risks of sending Colin to school

While daily infusions and vigilance have become a way of life for the Bazinsky family, Kate and Jordan, Colin’s father, were nervous about sending him to school. They knew his teachers would not be able to watch him as closely as his family did. He would be in a class with other students and have many opportunities to get hurt, especially on the playground. Despite their anxiety, they decided the benefits for Colin outweighed the risks.

Staff at the Boston Hemophilia Center at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center and the New England Hemophilia Association, encouraged Kate and Jordan to see if they could educate the staff at his new school about his condition. The more Colin’s teachers understood hemophilia, they reasoned, the more comfortable everyone would be. When Kate approached Temple Beth Avodah Early Learning Center to propose a training for Colin’s teachers, Heidi Baker, the school’s director, suggested the entire school’s staff attend.

A lesson in hemophilia — and Colin

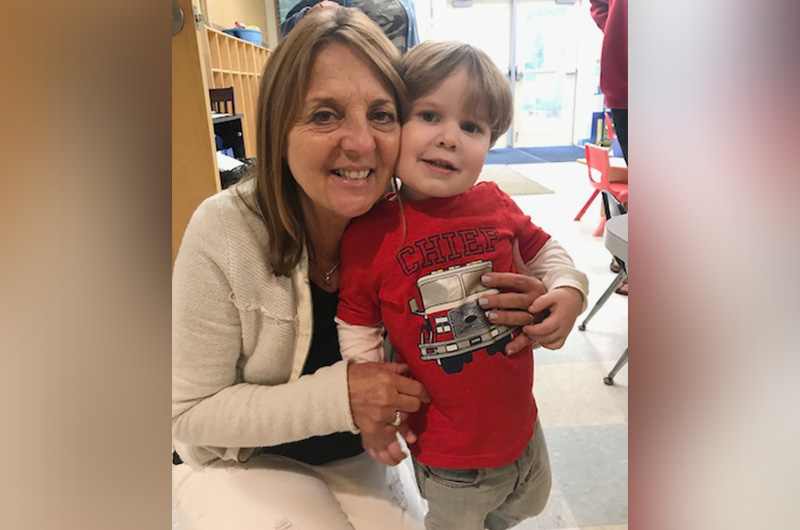

Maura Padula, a nurse educator from Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s, kicked off the presentation with an explanation of hemophilia and what to be concerned about. Next, Kate briefed the school’s staff and teachers on Colin: his personality, words he typically used when talking about hemophilia, and how to respond if he got hurt. “I wanted them to see and treat Colin as a normal kid,” says Kate. “Yes, we have to work a little harder to keep him safe, but I wanted them to feel confident they could have the same rules for him as for all the other kids. But if he got hurt, I wanted them to know how to respond appropriately.”

Colin’s teacher, Joan Jennings, remembers how anxious she felt at first. Colin would be the first child with hemophilia she and many others had in their classrooms. But everyone at the school took advantage of the chance to plan ahead. “We created a group text so if any incident occurred, we could contact Colin’s parents right away,” says Joan. “And Kate made it clear that she was always a phone call away if we had any concerns.”

Colin aces preschool

Colin spent his first year of preschool climbing, sliding, and playing with his classmates. When he got a cut or a bruise, his teachers would send a text to Kate, often with a photo of the injury. To everyone’s relief, he never needed medical attention for anything that happened on school grounds. That same year, the family made numerous trips to Boston Children’s for lab work, adjustments to Colin’s factor therapy, or when he fell or bumped into something at home. “The incidents tended to happen in the hour before bedtime, when he was tired and wild,” says Kate.

In the spring, Joan and the other teachers returned the medical kit Kate had provided at the start of the school year. They hadn’t had to use it once.

In early September, Colin returned for his second year of preschool, after Kate provided another training for the school. By then, most of the teachers knew Colin and were far more comfortable in their ability to respond if something happened. “I hope other families know that if teachers receive the right training, their child can have a normal, happy, safe classroom experience,” says Joan.

Tips for parents of children with hemophilia

- Harness the power of knowledge. Whether it’s educating grandparents or making a presentation to your child’s school, “communication is key,” says Colin’s teacher, Joan. “Understanding hemophilia, and having the chance to ask questions, gave all of us at the school a chance to plan ahead.”

- Keep yourself in check. “When your child has hemophilia, you can feel like you are one moment away from disaster at any time,” says Kate. “But if you’re afraid and anxious, your child will become afraid and anxious.” While different parents will have different outlets, yoga helps Kate remain vigilant without becoming hyper-vigilant.

- As your child gets older, give them room to figure things out. Colin is still young enough to go along with his parents’ game plan, but Kate knows this will change over time. Based on advice from other hemophilia parents, she knows she’ll need to give Colin freedom to make decisions for himself. “I’ve heard from a lot of parents of older kids not to let your fears dictate what your child can or cannot do. Let them try things and see if, with the right treatment protocol, their bodies can handle the activity. If they can, great. If not, focus on the limitations of their body rather than your fears. I’m sure it won’t be easy, but we hope to avoid power struggles with Colin as he gets older.”

Learn more about the Boston Hemophilia Center.

Related Posts :

-

Tough cookie: Steroid therapy helps Alessandra thrive with Diamond-Blackfan anemia

Two-year-old Alessandra is many things. She’s sweet, happy, curious, and, according to her parents, Ralph and Irma, a budding ...

-

Unique data revealed just when Mickey’s heart doctors could operate

When Mikolaj “Mickey” Karski’s family traveled from Poland to Boston to get him heart care, they weren’t thinking ...

-

It’s all in the PV loops: New analytical model could improve circulation assessments before heart surgery

The double-switch operation corrects the congenital reversal of the heart’s ventricles and its two main arteries. It’...

-

Blood across our lifetimes: An age-specific ‘atlas’ tells a dynamic story

The stem cells that form our blood, also known as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), are with us throughout our lives. ...