Osteosarcoma patient gets chance to be a ‘normal college kid’

For almost half of his life, Michael Murray has had to grapple with cancer, including multiple relapses. One of his hardest setbacks was hearing that his cancer had returned just weeks before he was set to start his freshman year at Boston College.

With the news, Michael worried that his future would be in jeopardy. Then, his care team at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center presented him with a plan that would allow him to settle into college life while also getting the best possible treatments.

“The way my Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s team listened to me and treated me made all the difference,” explains Michael, 20. “I was able to undergo treatment while still having fun and getting a chance to be a ‘normal college kid.’”

A surprising discovery

When Michael was 13 years old, he started experiencing terrible pain in his left knee. The athlete initially assumed he tore or tweaked something in his knee, and it took multiple trips to the doctor’s office before Michael underwent an MRI. The scan revealed a mass, and a biopsy confirmed it was cancer — specifically osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer.

Michael underwent treatment in his hometown of Chicago, where he first needed chemotherapy to shrink the tumor before it could be surgically removed through a procedure known as limb-salvage surgery. The surgery preserves the limb by removing the part of the bone involved with the tumor and some of the tissues that surround it.

Following the original operation, Michael had a number of setbacks, triggering additional surgeries. Ultimately, he and his team elected to use part of his right fibula (the shorter of the two bones that make up the shin) to help reconstruct his left leg. The procedure was a success, and today Michael enjoys full mobility in both of his legs.

“The procedure allowed me to play sports again, and that was a huge mental boost,” Michael says.

Starting over

After his surgery, Michael hit the ground running and was back playing sports. But a year after his diagnosis, his doctors found a spot in his lung, indicating that his cancer had spread. Michael would need surgery to remove this nodule.

“Hearing the cancer had returned was incredibly difficult because you think about all the progress you’ve made and how you’re going to have to start over,” says Michael. “I’ve had really difficult moments and difficult months, but I refuse to let the bad news get in the way of my recovery.”

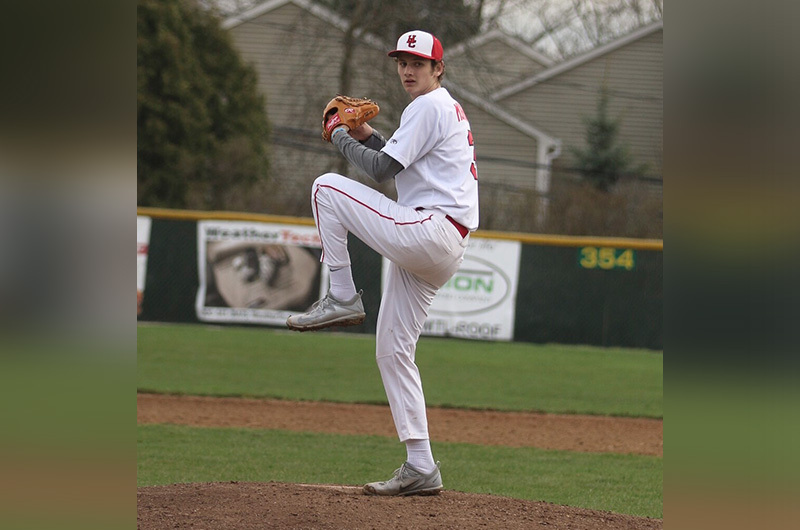

The surgery was deemed successful, and there were no signs of cancer for the rest of Michael’s time in high school; he was even able to play baseball. Unfortunately, with less than a week to go before his move to Boston College, Michael had to confront a new reality: His cancer had returned a second time to the exact same location in his lung.

A new option

After consulting with his family and team in Chicago, he decided to go through with his move and transfer his care to Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. He was placed under the care of Dr. Katherine Janeway, senior physician at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s and director of Clinical Genomics at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Michael would need surgery again, as well as additional treatment since he had already relapsed once. Rather than receive chemotherapy, Dr. Janeway proposed an alternative: a treatment plan including a post-surgery radiation and a new targeted cancer therapy, called a multi-targeted kinase inhibitor. Kinase inhibitors work by blocking particular enzymes (known as kinases) which help control certain cell functions, including metabolism, division, and survival. The goal of these drugs is to keep cancer cells from growing by blocking these cell functions, as well as the formation of new blood vessels in certain areas that tumors can use to grow.

Following the completion of this treatment, Michael has remained in remission for over a year.

As kinase inhibitors continue to show promising results for patients with relapsed osteosarcoma, like Michael, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s has opened clinical trials to study how they could work with other drugs.

“There hasn’t been any significant progress in osteosarcoma in many years, but these clinical trials could help provide new options and outcomes for patients who desperately need them,” explains Dr. Janeway.

Celebrating each victory

Despite his setbacks, Michael considers himself lucky. Thanks to the flexibility he found at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s, he’s been able to enjoy his college experience, and currently lives with the friends he made during his first week of school. His cancer journey has also led to an interest in orthopedics and sports medicine; Michael plans to enroll in medical school to pursue these passions following his college graduation.

Whether it’s playing softball with his friends, attending a Boston College tailgate, or just relaxing with his family, Michael has made it a habit to never take anything for granted.

“It’s OK to feel sad and down at times, but I’ve always tried to get through treatment with a smile on my face,” says Michael. “Every little victory is worth celebrating, and I’m lucky enough to be surrounded by the people I love.”

This post originally ran on the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s blog, Insight.

Learn more about Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

Related Posts :

-

Dancer stays on toes during kidney cancer treatment

Carly Tobin loves dancing for the fun and freedom it provides. During treatment for a rare pediatric kidney cancer known ...

-

Crista forms lifelong friendship with her cancer doctor

It’s impossible not to notice the connection between Crista Cardillo and Dr. Kim Stegmaier. The way they laugh and ...

-

Poverty predicts worse cancer outcomes, even in children receiving top-tier care

A pair of recent studies suggests that even among patients receiving advanced cancer care, poverty is a predictor of worse ...

-

Precision chemo-immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer is highly lethal and in great need of better treatments. Only about 10 percent of patients remain alive five ...