A vaccine to prevent opioid overdose?

Sharon Levy, MD, MPH, who directs the Adolescent Substance Use and Addiction Program (ASAP) at Boston Children’s Hospital, was getting her youngest son ready for school, when her husband Ofer, an infectious disease physician at the same hospital, came to her with an offer. The NIH was soliciting proposals to develop an opioid vaccine. Would she partner with him to seek a grant?

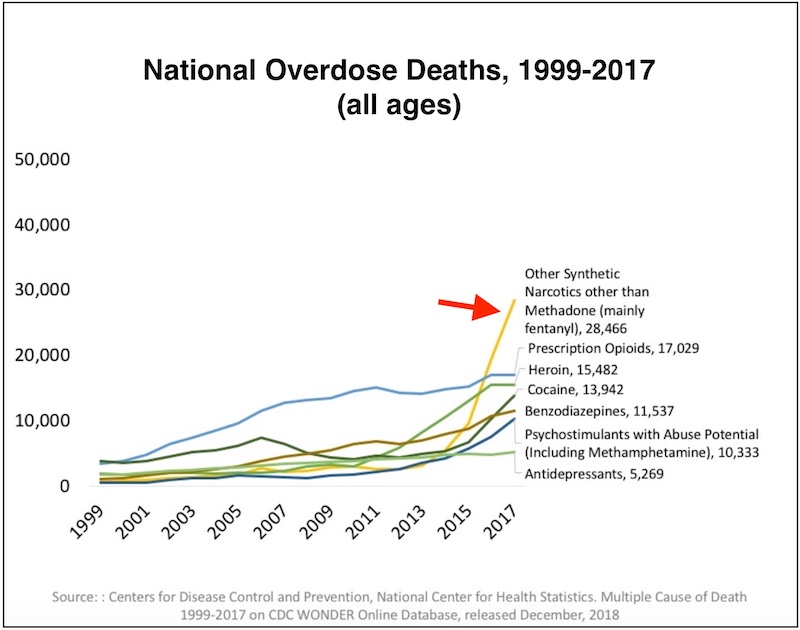

Levy agreed. For the past 15 years, ASAP has been treating teens and young adults with opioid use disorders who are trying to get off opioids. All are at risk for fatal overdoses, largely from fentanyl, a synthetic, highly potent opioid that is often added to other drugs like heroin, cocaine, and sometimes even marijuana. In 2017, fentanyl accounted for some 40 percent of the more than 70,200 fatal drug overdoses in the U.S:

“We’re now seeing most opioid overdoses coming from fentanyl — earlier it was pills and then heroin,” says Levy. “Some people simply do not know they’re using fentanyl; others seek it out because they have become tolerant to other opioids.”

Targeting fentanyl

Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, who directs the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s, was well positioned to develop a vaccine approach. He has long partnered with program faculty member David Dowling, PhD, in the development of vaccine adjuvants, which boost immune responses to vaccines. The Precision Vaccines Laboratory has also developed methods of modeling human immune systems representing different age groups — from newborns to the elderly — outside the body. And Sharon and her team had access to a young population of opioid users in which to test vaccine candidates.

A proposal quickly came together, and the Levys, together with Dowling, were awarded $2.3 million to develop an adjuvant/vaccine combination to guard against accidental fentanyl overdoses. The idea is that recipients would produce antibodies that would attach to fentanyl and bar it from entering the brain. The two-year pilot project is jointly funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Seeking opioid users age 15 to 30

The ASAP team began enrolling its patients in the study in late July. Over time, the study aims to enroll 20 to 25 youth meeting criteria for opioid use disorder, ages 15 to 30, and a similar number of controls from the community. Each participant will provide a blood sample, which the scientific team will use to develop in vitro models of immunity. The models will replicate key aspects of the human immune response outside the body, complete with different types of immune cells. Eventually, these models will be used to test candidate vaccines and adjuvants and to compare responses in immune systems of different ages and different histories of opioid exposure.

The project could yield new information about the teenage/young adult immune system.

“There are relativity few studies in the literature on that,” says Dowling. “Plus, we know that opioids change the immune system.”

Once the human immune assays identify a lead formulation, collaborators at the University of Houston will test it in rodent models of opioid addiction. The project is also tapping Inimmune, a Montana-based company, for its expertise in immunotherapeutics and medicinal chemistry. The company has experience with hapten vaccines, in which the molecule you want to protect against — in this case, fentanyl — is very small, so must be linked to a larger molecule in order to spark an immune response.

Putting an opioid vaccine into practice

The researchers, together with collaborators, are applying for a larger federal contract to eventually test the vaccine in humans. Future work will also explore the possibility of a vaccine that would protect against overdoses of opiates other than fentanyl.

In the meantime, the project raises a number of questions. Who should get the fentanyl vaccine if one is successfully developed? Should it be offered to people using drugs other than opioids? Would teens accept these vaccines? Would their parents be willing for them to get it? And would the vaccine’s availability make people feel less inclined to try to quit opioids?

“That’s my end of the work,” says Sharon Levy.

“One big unknown is whether a vaccine would treat opioid cravings,” she says. “Vaccines may turn out to be a very important component of treatment. It’s the Precision Vaccine team’s job to figure out how to design vaccines that can make a strong antibody response against opioids, and ASAP’s job to figure out how to incorporate such vaccines into treatment that helps patients stop using drugs.”

Related Posts :

-

A better treatment for endometriosis could lie in migraine medications

Endometriosis is a common, mysterious, often painful condition in which tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus, ...

-

Model enables study of age-specific responses to COVID mRNA vaccines in a dish

mRNA vaccines clearly saved lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, but several studies suggest that older people had a somewhat reduced ...

-

Will people accept a fentanyl vaccine? Interviews draw thoughtful responses

In 2022, more than 100,000 people died from opioid overdoses in the U.S., according to the National Center for Health Statistics. ...

-

Four ways to support your teen’s mental health

Being a teen is hard enough, but with the current adolescent mental health crisis, parents should know about the psychosocial ...