Injected microbubbles could be a safe way to deliver emergency oxygen

For years, researchers and clinicians have been trying to find a way to rapidly deliver oxygen to patients when traditional means of oxygenation are difficult or ineffective during critical moments of cardiac or respiratory arrest.

Sometimes, hypoxemia caused by airway obstruction or lung disease can be so severe that methods to boost low-oxygen levels (including the placement of a breathing tube) are ineffective. A patient can have cardiac arrest, potentially leading to severe organ damage. Research has shown that as many as 40 percent of in-hospital cardiac arrests are triggered by low-oxygen levels.

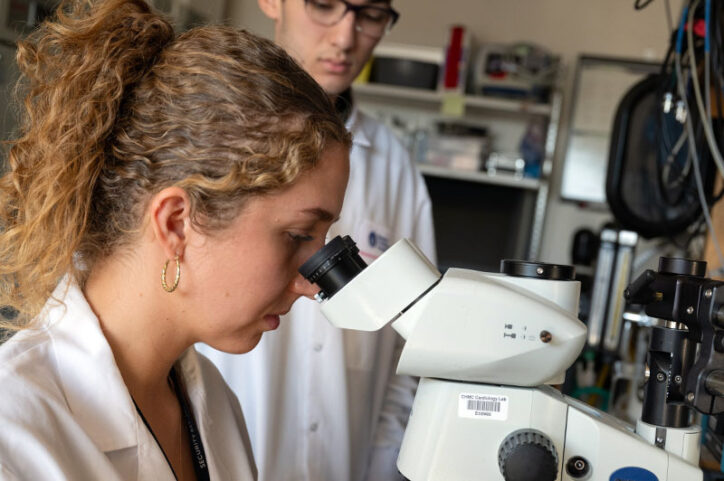

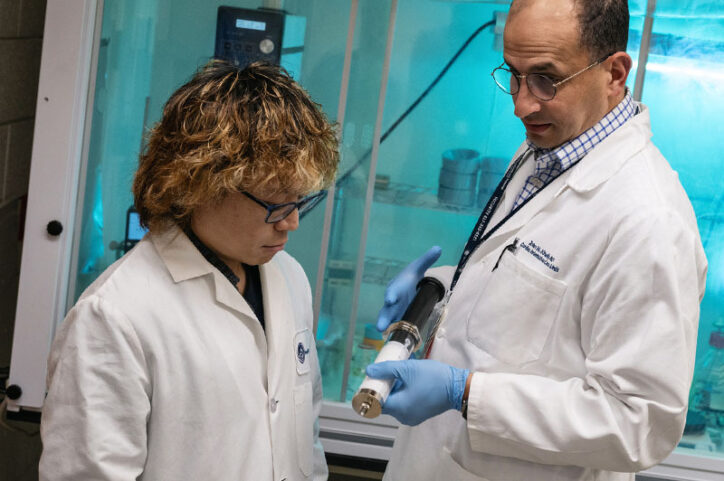

After 15 years of research, Boston Children’s cardiologist John Kheir, MD, and researcher Yifeng Peng, PhD, believe they have developed a safe and effective oxygen delivery method for those emergencies: injectable oxygen carried into the bloodstream by a rapidly dissolving gas microbubble. In pre-clinical testing, Kheir and Peng injected specifically designed pH-sensitive microbubbles that delivered precise amounts of oxygen and significantly improved survival by preventing catastrophic organ damage.

Their work paves the way for a future clinical trial, and they are excited by the promise of the innovation. “This opens a door to potentially creating a controlled and predictable way of providing necessary oxygen during hypoxemia, cardiac arrest, and other shock states,” Kheir says.

Searching for the proper oxygen-delivery system

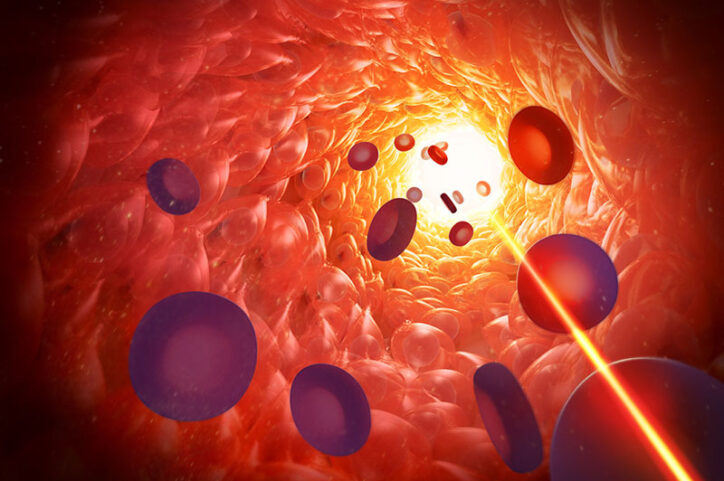

It might seem counterintuitive, Kheir says, that a shot of oxygen would make a difference in a vast system that circulates, in adults, about 200 milliliters of consumed oxygen per minute. But he and Peng have long believed that if a single dose of oxygen was given through an injectable gas carrier “at just the right time and to just the right place,” it could make a difference. They just needed time to prove it.

They first experimented with lipid-coated microbubbles, but the bubbles coalesced in the bloodstream and would have created a lethal embolism if they were not injected at a precise rate. The failure helped them recognize that the bubbles needed to be designed in a way that prevented them from coalescing.

A second attempt focused on hollow-core polymeric microparticles, but those failed to deliver a meaningful amount of gas to circulation. Kheir and Peng went back to the drawing board again.

Injected oxygen worked in test group

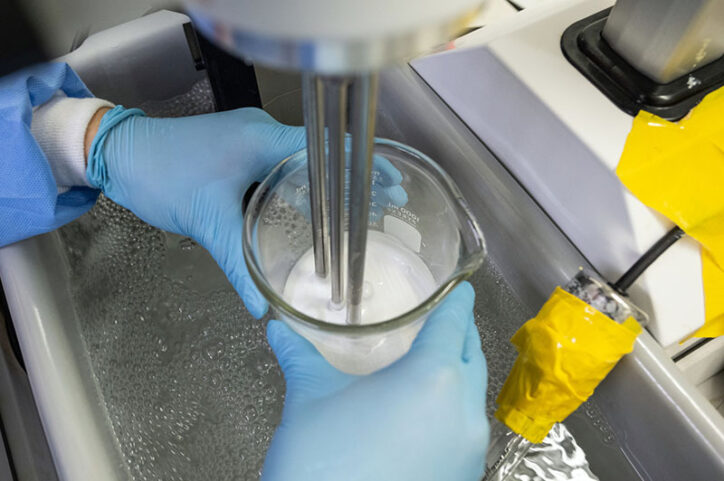

Their third attempt combines the best aspects of previous approaches. The new gas carrier is a microbubble that’s engineered with a solid-like polymer shell which, after being triggered by blood pH, dissolves into tiny soluble molecules that can then be excreted from the body. That makeup keeps the drug stable in storage and allows it to be injected during critical situations such as cardiac arrest.

A promising finding after 15 years of research

Read Kheir and Peng’s research findings in Nature Biomedical Engineering to learn how they tested their injected oxygen delivery method. “It was probably the most dramatic difference in outcomes between two test groups that I’ve ever seen in research,” Kheir says.

Their research is the first anywhere that showed a gas carrier of oxygen can be rapidly and safely delivered in a large dose to animals, Peng says. The key to success is that a microbubble has to dissolve rapidly, otherwise it will cause blood-flow obstruction.

“Injecting gas into your bloodstream is considered a horrible idea, and people would be afraid of that as a solution on its own,” Peng says. “But as long as that bubble dissolves quickly, you can actually inject a lot.”

Peng and Kheir received a competitive grant from Harvard Medical School to start manufacturing and testing the drug in anticipation of a clinical trial. They first need to create manufacturing practices aligned with Food and Drug Administration regulations. But after 15 years of trial and error, those steps seem like they can be achieved in far less time.

“It’s exciting,” Kheir says. “It’s not just a potential solution for this medical issue. It’s a platform technology. There are a lot of other gases we can put in and there are a lot of other medical situations suitable for a focused amount of gas delivery. The possibilities of what we can do with a drug like this are numerous.”

Learn more about the Department of Cardiology’s Translational Research Lab and the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit.

Related Posts :

-

Finding a possible genetic treatment for rare arrhythmias

Variants in a gene that plays a key role in heart function can cause potentially life-threatening arrhythmia syndromes known as ...

-

Eight years of preparation for a surgical first: a partial heart transplant

Boston Children’s cardiac surgeons have an overriding goal for each patient: If possible, repair their congenital ...

-

Finding ways to reduce the financial and social costs of pacemakers

As the number of complex heart operations has increased over the years, so have cases of postoperative heart block, a ...

-

Ductus arteriosus stenting could help severely ill infants with pulmonary arterial hypertension

Treatment for infants who have severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is sometimes limited. Because they haven’t physically ...