Social and emotional health in high school

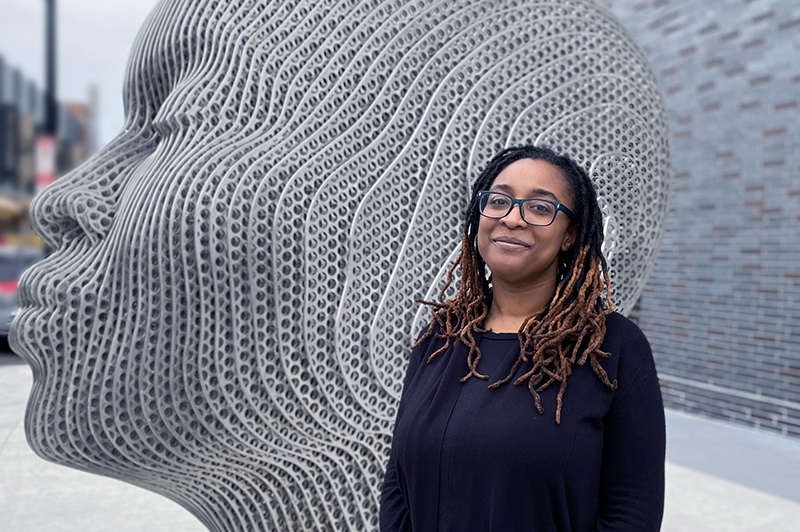

Sarauna Moore has a unique perspective on students’ emotional and behavioral health. As part of the Boston Children’s Hospital Neighborhood Partnerships team, she is a fixture at Boston Arts Academy (BAA), a public high school for the visual and performing arts. When in-person classes resumed in 2021 after a year of remote learning, she noticed a change in students’ emotions and relationships. Social skills that students would typically have developed through daily in-person interactions were largely missing and personal and interpersonal conflicts at the school increased.

After a challenging first year back, the atmosphere at the school improved. In many ways, students are back, taking classes, discovering themselves, and navigating relationships. Here, Moore talks about the remarkable strengths she sees in students that give her hope — and how students can develop some of the social and emotional skills that waned during the pandemic.

What do you admire in the students you work with?

There’s a real tenacity in these kids. In my position as a social worker, I recognize many of them are dealing with depression or anxiety. Some are dealing with stress at home or in their communities. And the school day starts at 8, even though we know that kids at this age need more sleep. But the students keep coming back and they keep trying.

I think we need to honor that type of effort. We need to clap for students who come to school even though they only got a few hours of sleep. We need to clap for students who may not be getting straight As but socially they’re killing it. Because guess what? Socially and emotionally, they have the skills to advocate for themselves. I see a lot to celebrate in these students’ efforts.

What skills are you working to help students develop?

One is emotional regulation. That starts with helping students understand their emotions and how to feel vulnerable without getting defensive, overwhelmed, or shutting down. Such skills can take a lifetime of work, but a lot of students enter high school thinking they should have them down already.

At BAA, the teachers, staff, and I try to normalize uncomfortable emotions. Starting at orientation, we tell them, “You will be overwhelmed. You will find yourself in situations where you don’t know what to do. That’s OK. This is a learning space.”

We also create opportunities for students to reflect on what their emotions could be telling them. If a student is feeling anxious or like everyone is staring at them, what can they do in response to that emotion rather than just feel embarrassed or lash out?

Why is it important that students learn to set boundaries?

If you can’t set a boundary, what are you going to say when someone asks you to do something you don’t want to do? Students need a lot of support in this area.

A lot of boundaries get crossed when a student is more worried about other people than they are about themself. This can show up in romantic relationships when one person doesn’t feel empowered to set physical boundaries. Or it can look like someone posting a conversation that the other person thought was private and not knowing how to say it was not OK to do that.

Students need to know — for themselves — what is OK and what is not OK with them. Then they need the language and self-confidence to let other people know where their boundaries are without letting fear of being judged or someone else feeling bad stop them.

What does conflict resolution look like and how can you teach it?

When conflict resolution goes right, both people are able to express their needs and reach a point of acceptance. It doesn’t have to mean you’re skipping into the sunset holding hands. Sometimes it’s a matter of agreeing not to take shots at each other online.

When conflict resolution goes wrong, people just explode because they don’t know how to express their needs effectively.

A lot of conflicts arise when someone’s needs haven’t been met. So, before we mediate a student conflict, we talk to each party to help them get clear on what they need and would like to see happen. We may role play difficult conversations and let them know it may bring up strong emotions — and that that’s OK.

How can adults help?

As adults, we need to let students know that there’s more than one path to success. You can’t be everything to every child, but you can help them build a robust community. The teenagers I see thrive are the ones who have a number of adults watching out for them and a variety of role models to emulate.

Learn more about the Boston Children’s Hospital Neighborhood Partnerships.

Related Posts :

-

Care in the classroom: Children's behavioral health in schools

If you want to address children’s social, emotional, and behavioral health, go to where the kids are — in schools. ...

-

Four ways to support your teen's mental health

Being a teen is hard enough, but with the current adolescent mental health crisis, parents should know about the psychosocial ...

-

Teens, anxiety, and depression: How worried should parents be?

Part of the work of being a teenager is making connections outside of the family and becoming attuned to world ...

-

Help your child manage anxiety about school violence

With news of school shootings and other violence often reaching children, parents sometimes grapple with how to help their child ...