New treatment guidelines for complex ADHD

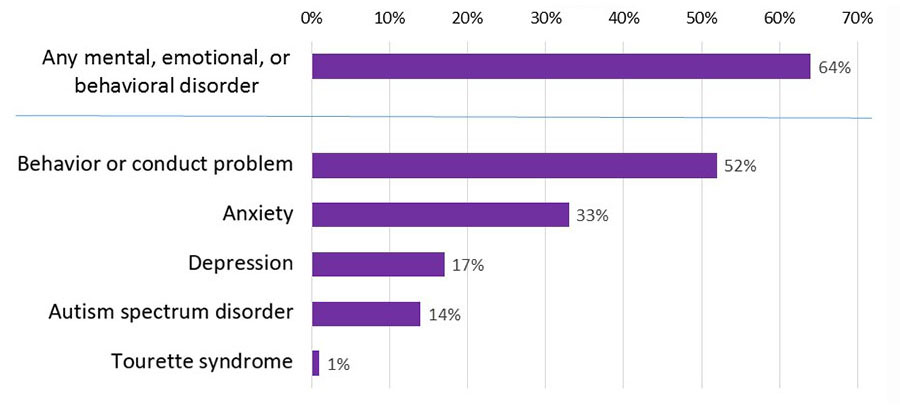

Approximately 7.5 percent of children and adolescents in the U.S. have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and about two-thirds of them have one or more co-existing conditions such as learning disorders or mental health problems. Treatment for these more complex forms of ADHD has focused largely on medical interventions. But now, a new clinical guideline calls strongly for providing psychosocial supports for children and adolescents with complex ADHD.

Developed by the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics (SDBP), the guideline provides a framework for diagnosing and treating complex ADHD in these children and adolescents. Its recommendations complement existing ADHD guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The new guideline is published in a supplemental issue of SDBP’s Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

“The time has come for us to take a determined step forward to improve the care and outcomes for people affected by ADHD,” says William Barbaresi, MD, chief of the Division of Developmental Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital and chair of the SDBP Complex ADHD Guidance Panel. “ADHD is not just an annoying childhood behavior problem. It is a neurodevelopmental disorder that can have a lifelong impact in key areas including mental health, educational and vocational outcomes, and relationships.”

A complex combination of conditions

Complex ADHD includes the presence of other conditions along with ADHD. These can include moderate to severe learning disabilities; intellectual disability; anxiety, depression, and other mental health problems; poor responses to treatment; and initial diagnosis of ADHD before age 4 or after age 12.

The new guideline focuses on identifying and treating more than “typical” core ADHD symptoms. It breaks new ground by recommending psychosocial treatment as an essential foundation for treatment of children and teens with ADHD, in addition to medications.

“Treatment for children and adolescents with complex ADHD should focus on improvement in function — behaviorally, socially, academically — over the patient’s life, not just improving ADHD symptoms,” says Barbaresi, who also wrote a commentary in the same special journal issue emphasizing the urgent need for updated treatment guidelines for these at-risk youth.

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial support goes beyond the realm of traditional drug treatments. They are intended to improve a patient’s ability to function well in common areas of daily living. A few examples may include:

- classroom-based management tools like positive reinforcement tools, daily report card, and posted expectations and consequences

- parent education

- organizational skills training

- approaches to improve appropriate peer interactions

- school services, such as 504 plans and special education individualized education plans (IEPs)

Five key action statements

The expert panel that developed the guideline found that the need for a dual approach — psychosocial intervention and medications — is supported by available research. “Psychosocial interventions are not consistently provided to patients in practice,” says Barbaresi, who explains that the lack of psychosocial supports has largely been driven by a lack of availability.

“One challenge has been the absence of emphatic, evidence-based recommendations by a professional organization,” he says. “This guideline is intended to provide those evidence-based recommendations.”

Specifically, the guideline focuses on five key action statements:

- Children under 19 with suspected or diagnosed complex ADHD should receive a comprehensive assessment by a clinician with specialized training or expertise, who should develop a multi-faceted treatment plan. The plan should be designed to diagnose and treat ADHD and other coexisting disorders and complicating factors including other neurodevelopmental disorders, learning disorders, mental health disorders, genetic disorders, and psychosocial factors like trauma and poverty.

- The evaluation should verify previous diagnoses and assess for other conditions; it should include a psychological assessment based on a child’s functional disabilities, and intellectual and developmental level.

- All children with complex ADHD should receive behavioral and educational interventions addressing behavioral, educational, and social success.

- Treatment of complex ADHD should also include coexisting conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder or substance abuse disorder, and focus on areas of impairment, not just reducing symptoms.

- Monitoring and treatment of complex ADHD should continue throughout life.

The guideline includes one-page summary diagnostic and treatment flowcharts for many complex ADHD scenarios including:

- behavioral/education treatment for children 6 years and older

- medication treatment for children 6 years and older

- treatment of ADHD plus a coexisting disorder including autism spectrum disorder, tics, substance use disorder, anxiety, depression, or disruptive behavior disorders

- preschool general medication treatment for children ages 3 to 6

Three-year review process

“The SDBP guideline is an important first step toward a more systematic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents with complex ADHD,” says Barbaresi. “We believe it has great potential to improve the treatment and long-term outcomes for these patients.”

The new SDBP guideline — the first-ever clinical practice guideline from the group — complements existing ADHD practice guidelines from the AAP, most recently updated in October 2019. It is intended to provide a framework for assessing and treating complex ADHD in children and adolescents by clinicians with specialized training.

The guideline was developed by an expert panel over three years, with panel members including developmental behavioral pediatricians, child psychologists, and a representative of CHADD, the national nonprofit family support organization for ADHD. The panel reviewed all previous ADHD treatment guidelines from the AAP and others, as well as a large body of published research related to each action statement.

In the same issue of the Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, guideline co-author Eugenia Chan, MD, PhD, a member of Boston Children’s Developmental Medicine Center, published a paper on the evidence review process the panel used for making its recommendation.

Next steps for the guideline committee will include the development of a toolkit to help implement the guideline in practice.

The guideline was developed with financial support by the SDBP.

Learn more about behavioral health supports.

Related Posts :

-

Promising advances in fetal therapy for vein of Galen malformation

In 2024, Megan Ingram* of California and her husband were preparing for the birth of their third child when a 34-week ...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...

-

A toast to BRD4: How acidity changes the immune response

It started with wine. Or more precisely, a conversation about it. "My colleagues and I were talking about how some ...

-

A unique marker for pericytes could help forge a new path for pulmonary hypertension care

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare condition that’s difficult to treat. The hallmarks of the disease — narrowing of ...