Food allergies: Turning tolerance back on

Hans Oettgen, MD, PhD, is Associate Chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Boston Children’s Hospital. He leads a research group investigating mechanisms of allergic diseases.

Not long ago I received a wonderful email from “Sam,” an 18-year-old young man with peanut allergy. He was participating in a clinical trial of oral immunotherapy (OIT) being carried out by colleagues here at Boston Children’s Hospital.

In OIT, patients receive initially minute doses of the food to which they are allergic. Then, over many weeks, they ingest increasing amounts, under close medical monitoring at the hospital.

OIT’s goal is to get patients to tolerate previously allergenic foods by inducing their bodies to produce Treg cells, or regulatory T cells. These are the master controllers of our immune responses, and their actions include suppressing allergic responses to foods. Food ingestion, as in OIT, will eventually induce food-specific Treg cells, but it can be a long and cumbersome process. For Sam, ingesting escalating doses of peanuts proved difficult: His email described frequent reactions ranging from stomachaches and itchiness to difficulty breathing.

I assumed Sam’s email would conclude by telling me he was quitting the trial. Instead, he described how relieved he was to reach the point where he could now eat a few peanuts.

Previously, accidental exposure to tiny bits of peanut (hidden in sauces, dressings or soups) had induced frightening reactions requiring emergency injection of epinephrine, administration of steroids and hospitalization. Being able to safely eat some peanut brought Sam tremendous peace of mind, lifting the cloud of anxiety around his future. He could now see himself traveling the world, trying new cuisines, starting his freshman year at college and simply living a more normal life.

A protective “cover” for food allergy therapy

While the concept of inducing food tolerance via OIT is gaining ground and trials are underway at a number of centers, we need to make OIT easier for patients and more effective. In short, we need a process that more effectively induces Treg cells, avoids unpleasant and potentially unsafe allergic reactions, and can be routinely carried out in a doctor’s office in days or weeks, rather than months—and without all the supports of a hospital-based clinical research team.

Recently, the independent efforts of clinical research teams and laboratory scientists at Boston Children’s have converged to offer hope. Both investigations have focused on immunoglobulin E (IgE), an antibody that recognizes foreign substances like foods.

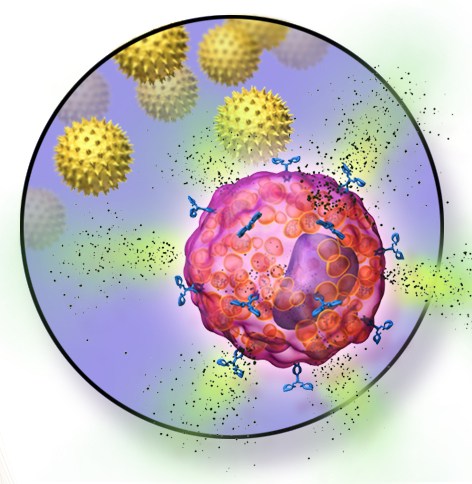

IgE antibodies bind tightly to mast cells, which populate our intestines and other places in the body exposed to foreign antigens. Mast cells, in turn, release histamine and other powerful chemical triggers of allergic reactions.

Clinical investigators including Lynda Schneider, MD, Rima Rachid, MD, and Dale Umetsu, MD, PhD, reasoned that blocking IgE would prevent mast cells from releasing these allergic mediators and help prevent allergic reactions. So they introduced the IgE blocking drug omalizumab to the OIT process. In an initial study of highly peanut-allergic patients, they found that OIT under cover of omalizumab was safe and effective.

The results, subsequently replicated at other sites, suggested that blocking IgE would allow OIT to proceed more rapidly and led to a national multi-center, placebo-controlled trial known as PRROTECT. Led by Schneider and Andrew MacGinnitie at Boston Children’s, the trial will carefully compare the results of OIT with and without omalizumab. (Sam enrolled in PRROTECT as soon as he learned he was eligible.)

A long-lived cure?

In parallel to these studies, my lab research group, in collaboration with the team of Talal Chatila, MD, also at Boston Children’s, discovered an important and unexpected benefit of blocking IgE during OIT.

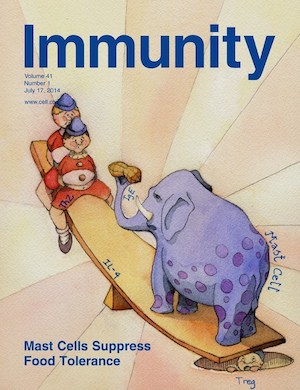

Working with mice that are highly susceptible to peanut allergy and using an array of approaches to alter IgE and mast-cell function, we found that mast cells don’t simply cause acute allergic reactions. They also turn off immune tolerance—by suppressing formation of the very Treg cells that curb the immune response.

Blocking IgE in the mice promoted Treg cell production, turning tolerance back on. For patients under going OIT, this unexpected finding is a huge potential boon. Most immunologists believe that successful food allergy treatment will require the induction of Treg cells, and that these cells will enforce long-lived tolerance, rather than just preventing acute allergic reactions in the short term.

It will now be important to move from animal experiments back to the clinic, through studies like PRROTECT, to test whether blocking IgE similarly supports Treg induction in humans. The ability to induce tolerance, simply by blocking IgE, provides hope that patients like Sam could have their allergies cured.

Related Posts :

-

Parsing the promise of inosine for neurogenic bladder

Spinal cord damage — whether from traumatic injury or conditions such as spina bifida — can have a profound impact on bladder ...

-

Team spirit: How working with an allergy psychologist got Amber back to cheering

A bubbly high schooler with lots of friends and a passion for competitive cheerleading: On the surface, Amber’s life ...

-

Unveiling the hidden impact of moyamoya disease: Brain injury without symptoms

Moyamoya disease — a rare, progressive condition that narrows the brain’s blood vessels — leads to an increased risk of stroke ...

-

Forecasting the future for childhood cancer survivors

Children are much more likely to survive cancer today than 50 years ago. Unfortunately, as adults, many of them develop cardiovascular ...