Could poop transplants treat peanut allergy? A clinical trial begins

Increasing evidence supports the idea that the bacteria living in our intestines early in life help shape our immune systems. Factors like cesarean birth, early antibiotics, having pets, number of siblings and formula feeding (rather than breastfeeding) may affect our microbial makeup, or microbiota, and may also affect our likelihood of developing allergies.

Could giving an allergic person the microbiota of a non-allergic person prevent allergic reactions? In a new clinical trial, a team led by Rima Rachid, MD, of Boston Children’s Division of Allergy and Immunology, is testing this idea in adults with severe peanut allergies. The microbiota will be delivered through fecal transplants — in the form of frozen, encapsulated poop pills.

Immunotherapy shortcomings

In the food allergy world, peanut and tree nut allergies have been the toughest to crack. They account for 90 percent of fatal or near-fatal allergic reactions, and are among the most persistent food allergies: only 15 to 20 percent of children grow out of them.

Oral immunotherapy (OIT) showed promise for peanut allergy at first, but long-term success rates are unclear and it hasn’t been proven to lead to a cure. OIT tries to build tolerance by feeding patients the allergy-provoking food in gradually increasing amounts. It is sometimes accompanied by medications such omalizumab (Xolair) to block immunoglobulin E (IgE), a protein involved in allergic reactions.

But in one study, only 12 of 24 peanut-allergic patients were able to weather a peanut challenge four to six weeks after undergoing OIT for as long as five years.

A Boston Children’s study added omalizumab to peanut OIT. Initially, 12 of 13 children became tolerant of up to 8 grams of peanut protein, the equivalent of about 20 peanuts. But most developed allergic reactions to peanut later in the study, or still show signs of allergy (blood elevations in peanut-specific IgE) after 4.5 to 5.5 years of maintenance therapy.

“It’s not clear if you can stop OIT without regaining sensitization,” says Rachid, who is leading that ongoing study.

Resetting the immune system

Immunologists have gone back to the lab to look for new biological pathways involved in food tolerance and food allergy. Other studies, embracing the hygiene hypothesis, have tried using probiotics.

Stacy Kahn, MD, of Boston Children’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, reviews the evidence for FMT’s benefit in recurrent C. difficile infection and other diseases.

“There are no significant results with probiotic studies,” says Rachid. “It is possible that you need a much larger consortium of bacteria. This is where the idea of fecal transplant came from.”

Rachid’s colleague Talal Chatila, MD, MSc, led a 2013 study that took the gut microbiota of an allergy-prone mouse and transferred the microbes to non-allergic mice — which then developed allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. Though the data have not yet been published, Chatila’s team also showed the reverse: microbiota from allergy-free mice protected allergy-prone mice from allergic reactions.

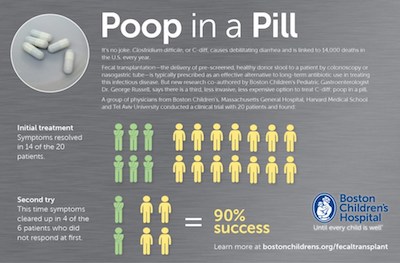

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) has now been used successfully for severe C. difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, and in animal models for other immune-related conditions such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Could FMT reset the immune systems of patients with peanut allergy?

Allergic vs. non-allergic babies: Comparing microbiota

As a first step, Rachid and Chatila asked: do children with food allergies have different intestinal microbiota than healthy children? With colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, they analyzed 240 stool samples from 59 babies with food allergies and 97 healthy controls. To identify the bacteria, they used a highly sensitive technique known as 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

The results, soon to be published, revealed 77 microbial species whose presence differed between food-allergic babies and controls across age groups (1-6 months, 7-12 months, 13-18 months and 19-24 months).

The group then gave allergy-prone mice a “cocktail” of bacteria resembling some of these strains. The animals were protected against anaphylaxis.

“These bacteria don’t exist in current probiotics,” says Rachid.

FMT for peanut allergy: Phase I

The new clinical trial, a Phase I open-label study, will enroll 10 adults (age 18 to 40) who must react during a food challenge with as little as 100 mg of peanut (less than half a peanut). The stool samples, from volunteer donors, are being provided by OpenBiome, the storied nonprofit stool bank.

The donors must be completely free of peanut and tree nut allergies, and must undergo nutritional training to completely eliminate any trace of peanuts and tree nuts from their diets, confirmed with a stool test. Finally, they must pass OpenBiome’s rigorous screening process: a 200-point clinical survey, followed by lab visits three days a week for two months so their stool and blood can be tested for harmful bacteria. The donated stool is quarantined for another 60 days, and released only if donors pass a second round of screening.

Patients who “pass” the baseline peanut challenge will receive two days of oral encapsulated FMT, given in Boston Children’s outpatient research unit. Four weeks and four months thereafter, they will repeat the peanut challenge, receiving doses of up to 2.5 peanuts, and undergo skin tests and blood tests. Each patient will provide stool samples for bacterial profiling for one year.

“To our knowledge, this is the first phase I trial that aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of FMT in peanut-allergic patients,” says Rachid. “If safety is proven, and we see a good response after the second and third food challenges and good results of the stool analysis, future FMT studies can be designed, with or without OIT.”

Rachid’s co-investigators are Chatila, Eric Alm, PhD, co-director of the Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics at MIT and Elizabeth Hohmann, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, who was among the first pioneers in evaluating oral FMT for C. difficile infection. George Russell, MD, formerly of Boston Children’s Division of Gastroenterology, collaborated with Hohmann and remains a consultant on the study.

The study should be complete in 2019. For more information, email study coordinator Meghan.Fitzgerald@childrens.harvard.edu.

Related Posts :

-

Team spirit: How working with an allergy psychologist got Amber back to cheering

A bubbly high schooler with lots of friends and a passion for competitive cheerleading: On the surface, Amber’s life ...

-

Partnering diet and intestinal microbes to protect against GI disease

Despite being an everyday necessity, nutrition is something of a black box. We know that many plant-based foods are good ...

-

A surprising link between Crohn’s disease and the Epstein-Barr virus

Crohn’s disease, a debilitating inflammatory bowel disease, has many known contributing factors, including bacterial changes in the microbiome that ...

-

Could peripheral neuropathy be stopped before it starts?

An increase in high-fat, high-fructose foods in people’s diets has contributed to a dramatic increase in type 2 diabetes. This, ...