Stool transplant found safe, effective for ‘C. diff’ in children

Diarrhea caused by Clostridiodes (formerly Clostridium) difficile infections is on the rise among children; one population-based study found a 12.5-fold increase in incidence from 1991 to 2009. For reasons that aren’t clear, C. difficile is more frequently striking children without the usual risk factors, such as hospitalization or antibiotic exposure. One thing that is known is that C. diff disease is associated with an altered intestinal microbiota.

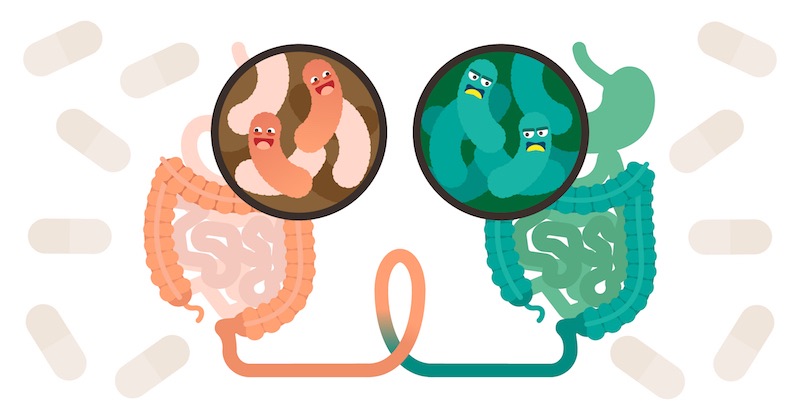

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), or the transfer of stool from a healthy donor to a patient, has been found highly effective in reversing severe, hard-to-treat C. diff in adults. The transplanted stool appears to restore the normal balance of microbiota. It can be administered in various ways, including colonoscopy, nasogastric tube, frozen capsules, or enemas.

What about children with C. diff? Is it safe to tamper with a developing child’s microbiota? When and how is FMT best administered? A new study in the journal Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the largest FMT study in children to date, found good outcomes and also identifies factors associated with success.

“Our results are quite exciting, given that recurrent C. diff is debilitating and increasing in children, not just those with known risk factors but previously healthy children as well,” says gastroenterologist Stacy A. Kahn, MD, at Boston Children’s Hospital. Kahn led the study with Maribeth Nicholson, MD, MPH, at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Richard Kellermayer, MD, PhD at Texas Children’s Hospital.

Factors in successful FMT

The team retrospectively studied 372 patients with C. diff, age 11 months to 23 years, who had FMT at one of 18 pediatric centers across the United States. Two-month outcomes were available for 335 patients. Of these, 81 percent had no recurrence of C. diff infection after a single treatment.

Some of the remaining patients had a second round of FMT. Of these, about half saw no C. diff recurrence, increasing the overall success rate to 87 percent.

Success was 2.7 times more likely when FMT came in the form of fresh versus previously frozen stool, and 2.4 times more likely when patients received the stool via colonoscopy versus other methods. Patients without a feeding tube (itself considered a risk factor for C. diff) were twice as likely to respond, and those with one fewer prior C. diff infection had a 20 percent greater chance of success. Age did not appear to be factor.

FMT was also more likely to succeed in patients treated more recently, perhaps because of tighter protocols around donor selection and treatment.

“The success rates we found are similar to what is seen in adults, but seem to be associated with fewer complications,” says Kahn. “We don’t understand why colonoscopic delivery, fresh stool and more recent FMT treatment were associated with higher success rates. These questions provide the foundation for future FMT research in children.”

As for safety, 6 percent of the patients had FMT-related adverse events; most were mild and included diarrhea, vomiting, and bloating. Of the roughly one-third of patients who also had inflammatory bowel disease, 2.5 percent had a severe flare of their illness requiring them to be hospitalized. But it wasn’t clear that had anything to do with the FMT.

Tapping FMT’s potential

Kahn notes that the study was limited by its retrospective design and relatively short period of follow-up. “We are using the data to help design future prospective, controlled studies,” she says. “We also need longitudinal studies to investigate the long-term impact and safety of transplanting the microbiome from one person to another. A lot more questions need to be answered.”

The group is also studying FMT for children with other forms of colitis, such inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“We want to tap into the therapeutic potential of FMT and begin to understand how we can use and manipulate the microbiome to treat diseases other than C. diff,” Kahn says.

Nicholson was first author on the paper (DOI 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.037). Kahn and Kellermeyer were co-senior authors. The study was supported by Cures Within Reach, a National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award, the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science, the Hamel Family, and the Neil and Anna Rasmussen Foundation.

Related Posts :

-

Hope in sight for autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA)

Autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA), the most common genetic optic neuropathy, is an insidious disease. It often presents slowly during ...

-

The dopamine reset: Restoring what’s missing in AADC deficiency

In March 2023, a young girl came to Boston Children’s Hospital unable to hold up her head — one striking symptom ...

-

Parsing the promise of inosine for neurogenic bladder

Spinal cord damage — whether from traumatic injury or conditions such as spina bifida — can have a profound impact on bladder ...

-

Team spirit: How working with an allergy psychologist got Amber back to cheering

A bubbly high schooler with lots of friends and a passion for competitive cheerleading: On the surface, Amber’s life ...