Regular physical activity linked to more ‘fit’ preteen brains

We know exercise has many health benefits. A new study from Boston Children’s Hospital adds another benefit: Physical activity appears to help organize children’s developing brains.

The study, led by Dr. Caterina Stamoulis, analyzed brain imaging data from nearly 6,000 9- and 10-year-olds. It found that physical activity was associated with more efficiently organized, robust, and flexible brain networks. The more physical activity, the more “fit” the brain.

“It didn’t matter what kind of physical activity children were involved in,” says Dr. Stamoulis, who directs the Computational Neuroscience Laboratory at Boston Children’s. “It only mattered that they were active.”

Crunching the data

Dr. Stamoulis and her trainees, Skylar Brooks and Sean Parks, tapped brain imaging data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a long-running study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. They used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data to estimate the strength and organizational properties of the children’s brain circuits. These measures determine how efficiently the brain functions and how readily it can adapt to changes in the environment.

It didn’t matter what kind of physical activity children were involved in. It only mattered that they were active.”

“The preteen years are a very important time in brain development,” notes Dr. Stamoulis. “They are associated with a lot of changes in the brain’s functional circuits, particularly those supporting higher-level thought processes. Unhealthy changes in these areas can lead to risky behaviors and long-lasting deficits in the skills needed for learning and reasoning.”

The team combined these data with information on the children’s physical activity and sports involvement, supplied by the families, as well as body mass index (BMI). Finally, they adjusted the data for other factors that might affect brain development, such as being born before 40 weeks of gestation, puberty status, sex, and family income.

Healthy brain networks

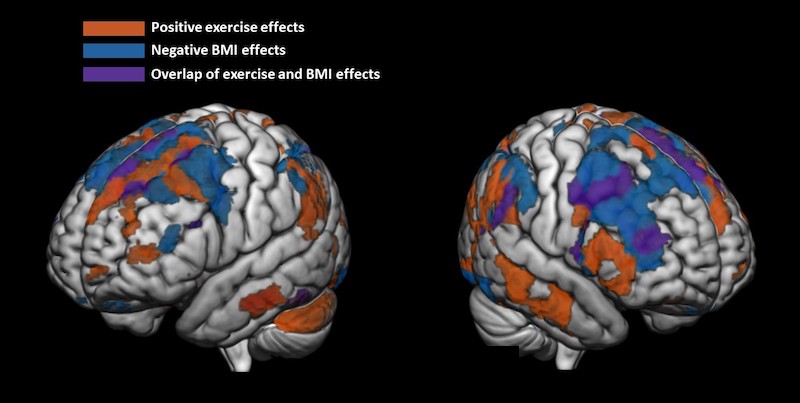

Being active multiple times per week for at least 60 minutes had a widespread positive effect on brain circuitry. Children who engaged in high levels of physical activity showed beneficial effects on brain circuits in multiple areas essential to learning and reasoning. These included attention, sensory and motor processing, memory, decision making, and executive control (the ability to plan, coordinate, and control actions and behaviors).

In contrast, increased BMI tended to have detrimental effects on the same brain circuitry. However, regular physical activity reduced these negative effects. “We think physical activity affects brain organization directly, but also indirectly by reducing BMI,” Dr. Stamoulis says.

Analyzing brain effects

In the analyses, the brain was represented mathematically as a network of “nodes”: a set of brain regions linked by connections of varying strength. Physical activity had two kinds of positive effects: on the efficiency and robustness of the network as a whole, and on more local properties such as the number and clustering of node connections.

More about this research

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation’s Harnessing the Data Revolution and BRAIN Initiative. The researchers developed advanced computing techniques to analyze the data with support from Harvard Medical School’s High Performance Computing Cluster. Findings were published last month in Cerebral Cortex.

“Highly connected local brain networks that communicate with each other through relatively few but strong long-range connections optimizes information processing and transmission in the brain,” explains Dr. Stamoulis. “In preteens, a number of brain functions are still developing, and they can be altered by a number of risk factors. Our results suggest that physical activity has a positive protective effect across brain regions.”

Learn more about Boston Children’s Computational Neuroscience Laboratory.

Related Posts :

-

Exploring brain operations: Making decisions, snapping to attention, and forming memories

How do our brains snap to attention and orient us to the outside world — like when we’re sound asleep ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity and ...

-

When diagnosis is just the first step: The Brain Gene Registry

Through advances in genetic sequencing, many children with rare, unidentified neurodevelopmental disorders are finally having their mysteries solved. But are ...

-

Infantile spasms: Speeding referrals for all infants

Infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (IESS), often called infantile spasms, is the most common form of epilepsy seen during infancy. Prompt ...