Building a better botox

Aside from reducing wrinkles, botulinum toxins — a.k.a. botox — have a variety of uses in medicine: to treat muscle overactivity in overactive bladder, to correct misalignment of the eyes in strabismus, for a movement disorder called cervical dystonia that causes neck spasms, and more. Two botulinum toxins, types A and B, are FDA-approved and widely used. Although they are safe and effective, the toxins can drift away from the site of injection, reducing efficacy and causing side effects.

Now, new research finds that some small engineering tweaks to botox B could make it more effective and longer-lasting with fewer side effects. The researchers, at Boston Children’s Hospital, reported their findings in PLOS Biology.

A third way for botox B to bind to nerves

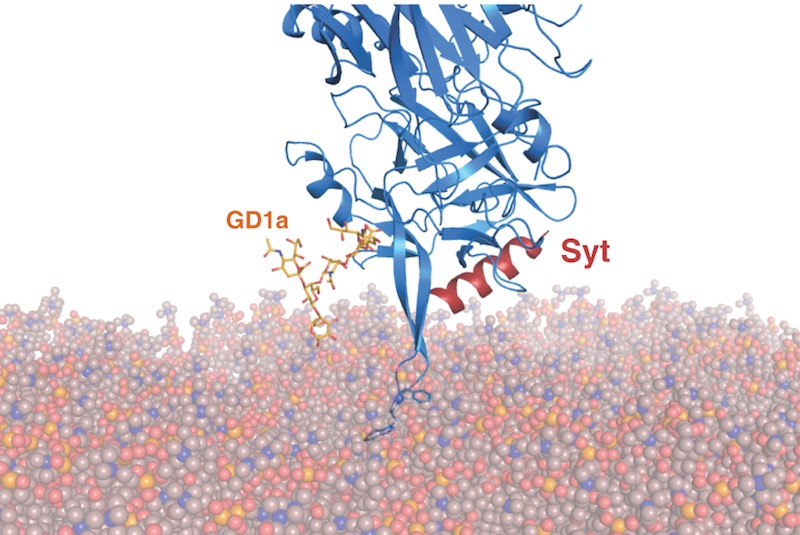

Botox works by attaching to nerves near their junction with muscles, using two cell receptors. Once docked, it blocks release of neurotransmitter, paralyzing the muscle.

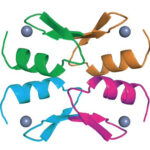

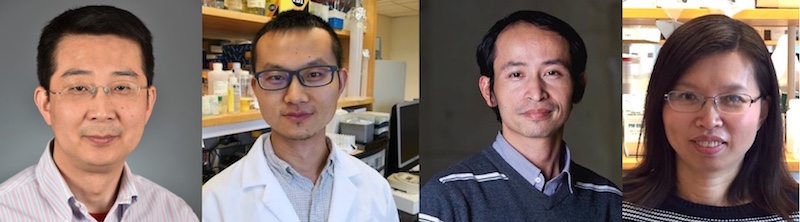

Min Dong, PhD, at Boston Children’s, with lab members Linxiang Yin, PhD, Sicai Zhang, PhD, and Jie Zhang, PhD, had been looking for ways to get botox B to bind to nerve cells more strongly, to keep it in place and avoid side effects. In another member of the botox family, type DC, they identified a potential third means of attachment: a lipid-binding loop capable of penetrating lipid membranes.

Through structural modeling studies, they discovered that when particular amino acids are at the tip of this loop, the toxin can indeed use the loop to attach to the nerve-cell surface, in addition to binding to toxin receptors.

Further, they found that although botox B contains this same lipid-binding loop, it lacks these key amino acids at its tip. So Dong and colleagues added them in through genetic engineering.

Enhancing botox as a therapeutic

As they had hoped, the introduced changes enhanced the toxin’s ability to bind to nerve cells. In a mouse model, neurons around the injection sites absorbed the engineered toxin more efficiently than the FDA-approved form of botox B, and less toxin diffused away from the injection site. This led to more effective local muscle paralysis, extended duration of local paralysis, and reduced systemic toxicity.

“Based on our mechanistic insight, we created an improved toxin that showed higher therapeutic efficacy, better safety range, and much longer duration,” says Dong. “The type A toxin does not have the lipid-binding loop, so we are still working on engineering this lipid-binding capability into type A.”

Boston Children’s Hospital has filed for a patent and hopes to bring the enhanced toxin into clinical development.

Pål Stenmark of Stockholm University is co-senior author on the paper.

Related Posts :

-

A new druggable cancer target: RNA-binding proteins on the cell surface

In 2021, research led by Ryan Flynn, MD, PhD, and his mentor, Nobel laureate Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, opened a new chapter ...

-

Modeling urinary tract disorders on a chip: Zohreh Izadifar

When a new tissue sample arrives from the Department of Urology, the Boston Children’s Hospital lab of Zohreh Izadifar, ...

-

Bringing order to disorder: Jhullian Alston, PhD

Proteins typically fold into orderly, predictable three-dimensional structures that dictate how they will interact with other molecules. Jhulian Alston, PhD, ...

-

Could a pill treat sickle cell disease?

The new gene therapies for sickle cell disease — including the gene-editing treatment Casgevy, based on research at Boston Children’s ...