Mouse model could lead to new treatments for endometriosis pain

There are few effective long-term treatments for endometriosis; even fewer options for relieving the often severe pain associated with the condition, which involves tissue overgrowth outside of the uterus. As a first step toward identifying new pain treatments, researchers in the laboratory of Michael Rogers, PhD, in the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, have developed the first mouse model that mimics the development, lesion growth — even the severe pain — associated with endometriosis. A paper describing the mouse model and its potential use for developing new pain medications was published in the journal Pain.

Creating clinical endometriosis

Along with infertility, the often debilitating pain from endometriosis is a major problem for many women. “There are very limited numbers of drug options available for treatment and my focus is to expand those options,” says Rogers. Common drug treatments now include ibuprofen and hormonal treatments aimed at reducing estrogen levels.

Earlier attempts at developing a mouse model for endometriosis pain were hindered by various problems. Most attempts required surgery on the mice to trigger endometriosis development. But results were limited due to the fact that surgery, even laparoscopic surgery, changes the pain response.

To overcome that challenge, Rogers’ team induced endometriosis non-surgically. They injected small bits of mouse uterine tissue into the mouse abdomen to stimulate endometriosis growth. By the end of a typical experiment (eight weeks after injection), 90 percent of the treated mice developed visible endometriosis lesions.

Lesion analysis and behavioral testing

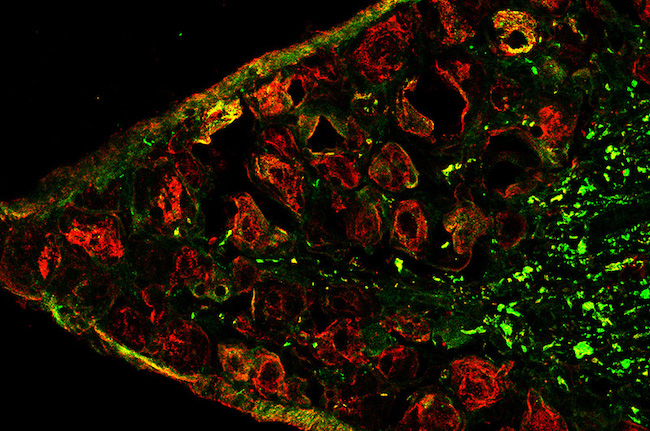

Pathology reviews ensured that the lesions resembled those found in human endometriosis. Tissue from the endometrial growths contained the three hallmarks of the disease in humans: endometrial glands, endometrial stroma (connective tissue), and hemosiderin (an iron-storage complex).

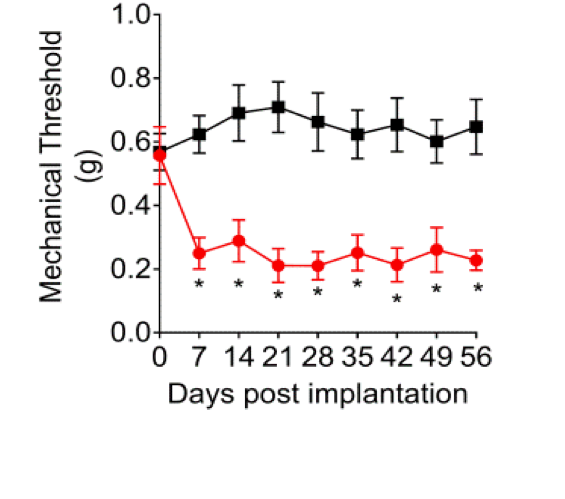

Once the lesions were established, the team used five measures to test for pain in the mice, including one that involved stimulation of the abdomen.

“We know that for many women with endometriosis, their abdomens become substantially more sensitive to touch,” says Rogers. The researchers found that the mice responded similarly. In addition, the team noticed behavioral signs of discomfort — such as pushing their abdomens against a cage floor, abdominal stretching, and direct licking of the abdominal area.

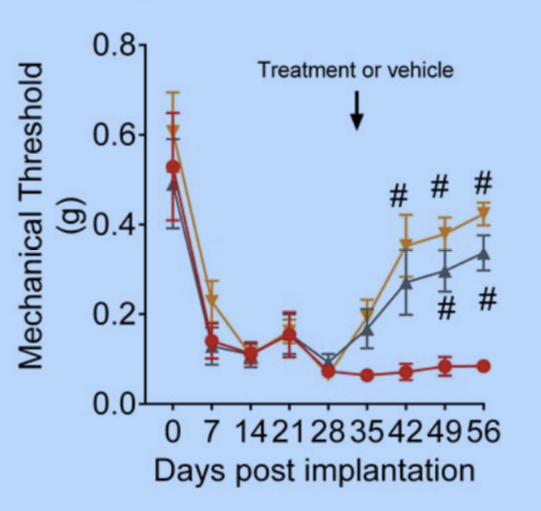

Targeting disabling pain

The team next treated the mice with two drugs that are known to help women with endometriosis. Letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, decreases the production of estrogen. Danazol, an androgen, also decreases estrogen production indirectly through its action on the pituitary. The team saw dramatic decreases in all of the five markers of pain in the test mice. The drugs also reduced the number of mice with visible lesions compared with a control group of mice.

“Now, we know we have a model that we are reasonably comfortable reflects the experience of women with drug therapy,” says Rogers. “We now have a way to test all types of medications for relief of endometriosis pain, including those relieving the chronic pain that often accompanies long-term endometriosis.”

In preliminary results, Rogers’ team has already experimented with about a dozen different drugs. They have already found multiple different drugs and pathways that affect endometriosis-associated pain. These are mostly drugs that have not been tested in women with endometriosis in the past.

Testing potential new drugs

As the team discovers and validates drug candidates, the results are forwarded to others at Boston Children’s who are initiating clinical trials. One of these important collaborations is with Amy DiVasta, MD, co-scientific director for the Boston Center for Endometriosis and a physician in the Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine. DiVasta is currently conducting a Phase II clinical trial of cabergoline for endometriosis.

It is my goal to make sure that we provide a steady pipeline of potential new drugs from our model into the clinic. We want our model to provide enough data so that we can pass them along to other investigators doing the clinical testing.” – Michael Rogers, PhD

The Rogers team is now moving ahead testing dozens of additional drug candidates.

Victor Fattori, Noah Franklin, Daniëlle Peterse, and Aram Ghalali from the Vascular Biology Program contributed to this research. Additional contributions were made by Rafael Gonzalez-Cano, Nick Andrews, and Clifford J. Woolf, from the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Learn more about endometriosis research.

Related Posts :

-

‘Everything fell into place’: Innovative POEM procedure lets Peyton eat without pain

Peyton Reed, 14, is a typical teenage boy: He enjoys tennis, video games — and food. So when eating became so painful ...

-

One day closer: Second opinion for urologic pain changes Iker’s life at last

Like many kids, Iker Guzman enjoys playing with LEGO toys. But there was nothing lighthearted about the day a few ...

-

New possibilities: How Caden learned to manage chronic pain — and found an unexpected path

In October 2020, Caden Deutsch started feeling sick. Although the 17-year-old had been coping with juvenile idiopathic arthritis since he was ...

-

Broken signals: Things you may not know about nerve injury

When Dr. Andrea Bauer talks about nerve injuries, she talks about phone cords. A damaged phone cord transmits staticky or ...