The neurology resident that could

Elizabeth Engle used to wait in peoples’ driveways until midnight, hoping to enroll them in her genetic studies of eye-movement disorders. She landed there by chance: during her neurology residency, she saw a little boy whose eyes were frozen in a downward gaze. Wanting to find a solution to a disorder that others had written off, she talked her way into the muscular dystrophy genetics lab of Alan Beggs and Lou Kunkel at Children’s.

Why muscular dystrophy? That tragic muscle-weakening disease somehow spares the eye muscles. Engle thought if Beggs and Kunkel took her on, she could answer two questions at once – what was protecting the eye muscles in muscular dystrophy, and what had caused the little boy’s fixed gaze and droopy eyelids. Plus, she needed laboratory training to study the samples she’d started gathering. “I didn’t have a PhD and was never officially trained in the lab,” she once said. “I didn’t even know how to make chemical solutions.”

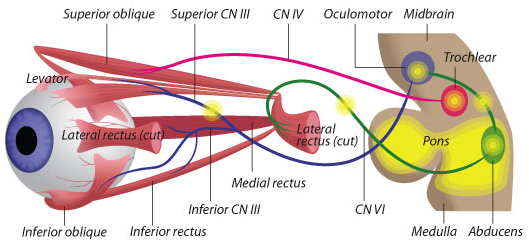

Engle’s research career was launched – bringing her into a world of inherited, socially isolating disorders that rob people of the ability to control their eye movements – leaving multiple family members with droopy lids, or unable to look left or right, or up and down, without tilting their head. Or sometimes a combination of these.

Breaking ground in genetic eye-movement disorders

Engle now has a database of more than 1,500 patients from all over the world (who now mostly mail their DNA samples) and multiple genetic discoveries to her credit. Though it seems she occupies a rather odd niche in ophthalmology, she’s also broken new ground in neuroscience – since, ultimately, it’s faulty nerve development and guidance that cause these disorders.

Having written about Engle’s science on several occasions, I’ve seen her tenacity firsthand. But I now appreciate her as a scientific adventurer, willing to step out of her comfort zone, learn new tricks and do whatever it takes to see a problem through. Read more in this wonderful profile in the HHMI Bulletin.

Related Posts :

-

Promising advances in fetal therapy for vein of Galen malformation

In 2024, Megan Ingram* of California and her husband were preparing for the birth of their third child when a 34-week ...

-

A case for Kennedy — and for rapid genomic testing in every NICU

Kennedy was born in August 2025 after what her parents, John and Diana, describe as an uneventful pregnancy. Soon after delivery, ...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, then a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity ...