Genomic sequencing transforms a life: Asa’s story

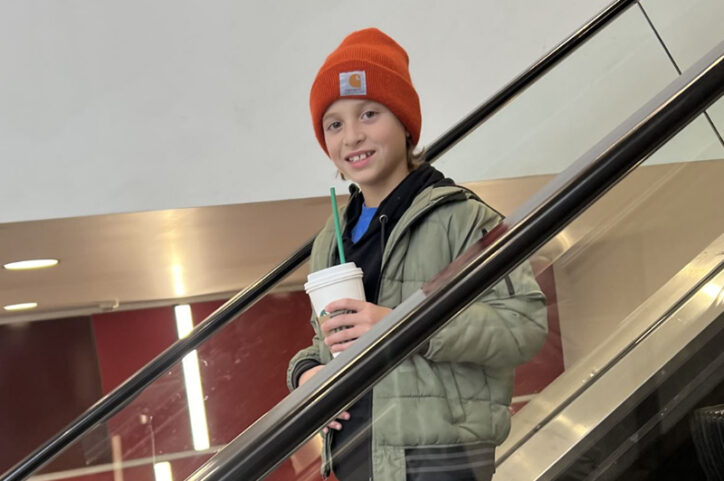

Asa Cibelli feels like he’s been reborn. The straight-A middle schooler plays basketball and football, does jiu jitsu, is learning guitar, and can solve a Rubik’s cube in 40 seconds flat. But he once wondered if he’d ever feel better.

From birth, Asa experienced chronic abdominal pain and severe diarrhea. The many doctors he saw at different medical centers in his home state of California couldn’t figure out why.

“We went from doctor to doctor to department to department,” says his mother Katie.

Asa’s first endoscopy, after his first birthday, was inconclusive. The pediatrician chalked his symptoms up to “toddler’s diarrhea,” but Katie suspected more was going on. After doing research, Asa’s parents put him on a specific carbohydrate diet, which eliminates grain products, sugar, dairy products, and processed foods.

Ruling out Crohn’s disease

At age 2, Asa’s weight gain and growth slowed precipitously. He reacted to every food he ate. After a bout with an intestinal C. difficile infection — his first of several — Asa was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

But Katie read up on Crohn’s disease and doubted that Asa had it. “His labs never showed elevated inflammation,” she says. “I thought, how could that be if he has IBD and is symptomatic?”

Despite consuming thousands of calories a day, Asa remained very small for his age. He seemed unable to absorb nutrients. Several endoscopies, starting at age 6, were clear, showing no signs of damage in his GI tract. An imaging study of Asa’s small intestine, magnetic resonance enterography, was also clear.

“He was starting to have rashes, joint pain, headaches, and night sweats,” says Katie. “He was unable to concentrate at school. His symptoms were just spiraling — yet his labs and his endoscopy looked great.”

There has to be something else, she thought. Asa was becoming anxious, depressed, and dispirited, wondering if he would ever feel better. His illness was interfering with school and sports practices.

“Not only did Asa not want to go to school due to very frequent bathroom visits and pain, but if he did make it to school, I often had to pick him up early,” Katie says.

By the time Asa was 10, Katie had decided they needed to go out of state. After a Google search, she set her sights on Boston Children’s Hospital.

In September 2023, they came to Boston and saw Dr. Stacy Kahn in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, who reviewed all of Asa’s endoscopies and consulted with her colleagues.

“Collectively, everyone agreed it’s not Crohn’s,” Katie says. “Dr. Kahn said, ‘We’ll figure it out.”

A mystery solved, and a simple solution

In January 2024, Asa returned and saw a variety of other specialists — genetics, rheumatology, hematology. None had seen a case like Asa’s before. He had so many lab tests that they were split between two visits.

He also met Dr. Jay Thiagarajah, co-director of Boston Children’s Congenital Enteropathy Program and a member of the Children’s Rare Disease Collaborative (CRDC), a hospital-wide research effort that seeks to find genetic causes of rare diseases. Through the CRDC, Dr. Thiagarajah ordered genomic sequencing for Asa and his parents.

“That was our last-ditch effort,” Katie says. “It was so frustrating, trying to keep my son’s spirits up. There were lots of puzzle pieces, but nowhere to put them.”

The genetic results, arriving about 10 weeks later, changed everything.

The analysis showed that Asa has an ultra-rare mutation in the SLC10A2 gene — the world’s sixth-known case. As a result, he lacked a protein needed to transport bile acids, which are essential for digestion. His liver was trying to compensate by overproducing bile acids, which flooded into Asa’s intestine.

“This irritates the colon, leading to excess secretion and diarrhea and causing nutrients not to be absorbed properly,” Dr. Thiagarajah explains. “Fortunately, there are medications to remove excessive bile acids in the intestine.”

In May 2024, Asa started a medication called cholestyramine. “Within 12 hours, his symptoms were gone,” Katie says. Encouraged, Asa began adding things to his diet one at a time. “We got 10 foods in, and he did not react.”

The following month, returning to Boston Children’s for another endoscopy, he temporarily stopped taking cholestyramine, and his symptoms came roaring back within 12 hours. Once he went back on the medication, the symptoms just as quickly disappeared.

Enjoying foods for the first time

Asa will likely need to be on cholestyramine, or drugs like it, for the rest of his life. But he can now tolerate all foods, even dairy, and go about living his life. “Last Halloween was the first Halloween where he could have candy — at age 11,” Katie says. “He had his first Christmas meal without dietary restrictions, first real pumpkin pie, his first Valentine’s Day candy.”

Since June 2024, Asa has gained almost 15 pounds and shot up almost 5 inches. He’s experienced no GI symptoms.

“This all happened because of Katie,” says Dr. Thiagarajah. “She didn’t think the various diagnoses he’d been given were right, and she didn’t let it go.”

Dr. Thiagarajah and his colleagues recently published a report in The New England Journal of Medicine that comprehensively defines the genetics of congenital diarrheas and enteropathies, a major step toward better care for these rare conditions. Read more about the findings.

Asa, now 11, agrees. “I’m so happy that my mom never gave up on trying to find out what was wrong, and thankful that the Boston doctors didn’t stop searching for answers for me. It basically changed my entire life.”

Katie credits Asa’s doctors at Boston Children’s and the support she received from her family. “Dr. Kahn and Dr. Thiagarajah didn’t give up searching for answers, and we wouldn’t be where we are today without them believing in me,” she says. “Asa’s dad and two brothers were amazing, making sure I had all the resources I need to get Asa to his appointments and to Boston, and to do all the research I have done to advocate for Asa.”

Learn more about care in Boston Children’s Congenital Enteropathy Program and the Children’s Rare Disease Collaborative (CRDC).

Related Posts :

-

Don't forget the cheese, please! Rachel's EoE journey

Like many teens, Rachel loves cheese and other dairy foods. “Cheese sticks, yogurt, and especially pizza,” Chellie, her mom, shares. ...

-

How one diagnosis brought together three best friends: Allyson, Maddy, and Caiya's journey with pancreatitis

Allyson, Maddy, and Caiya are your typical tween best friends — sharing inside jokes and constantly chatting about everything and anything. “...

-

Calm through the storm: Connor's ulcerative colitis journey

When you meet Connor today, he’s a confident 13-year-old who is incredibly laid back when he speaks about his ...

-

Changing lives through genetics: The Children’s Rare Disease Collaborative

A 14-year-old girl was having back pain after a car accident and visited an orthopedic clinic at Boston Children’s ...