Developmental milestone checklists don’t always agree, finds study

Developmental milestones, such as sitting unsupported or babbling, are a cornerstone for tracking a child’s development and spotting potential delays. Yet fewer than half of pediatricians actually use formal developmental assessments. Hoping to make the process easier, Carol Wilkinson, MD, PhD, in the Boston Children’s Hospital Division of Developmental Medicine, set out to incorporate a list of developmental milestones in patients’ electronic health records (EHRs).

But while developing a comprehensive list of milestones to include in the EHR, she discovered a greater problem. The milestone checklists she was reviewing, widely used by both clinicians and caregivers, had major inconsistencies.

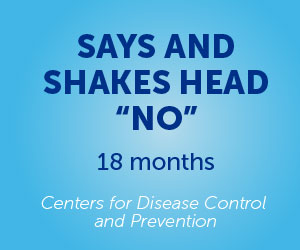

The CDC’s checklist cites ‘Dresses and undresses self’ at 36 months, whereas the Healthy Children’s checklist cites ‘Dresses and undresses without assistance’ at 60 months.

“Parents are often concerned about their child’s development, and there are a lot of resources online about which milestones to monitor and when they are supposed to occur,” Dr. Wilkinson says. “What we’ve found is that those resources aren’t that consistent with each other, and they’re also not consistent with the resources that doctors use.”

For example, one checklist says that children will “begin make-believe play” by 24 months. Another says they will “play by starting to include other children … such as play tea parties or chase games” at 30 months. Both checklists are trying to describe the same developmental observation — pretend play. But they describe it differently and cite different age ranges for the milestone.

Evaluating milestone checklists

For their study, Dr. Wilkinson and her colleagues selected four well-regarded milestone checklists for review. Two checklists were designed for parents and caregivers (CDC: Learn the Signs. Act Early and Healthy Children: Ages and Stages). The other two are aimed at physicians (Bright Futures, 3rd Edition and a checklist published in Pediatrics in Review).

As a first step, the team needed to create a master list of unambiguous, discrete, and objectively observable behaviors described by one or more milestones. Since the Pediatrics in Review checklist was the most extensive, and many of its milestones were written as objective observations, it became the foundation of the master list. The researchers then worked in pairs to match milestones from the three remaining checklists to the list. If a milestone did not match an observation on the list, a new observation was created. Through this process, the team created an observation-milestone relational database for further analysis.

Ultimately, the team found a total of 728 unique behavioral observations that mapped to more than 1,000 milestones from across all four checklists.

Milestone mismatch

Next, the team evaluated the variability between the milestone checklists. Shockingly, while each checklist boasted at least 170 individual milestones, only 40 of those milestones, on average, overlapped with the other three checklists.

Second, the team assessed how many unique behavioral observations mapped onto all four checklists. They found that only 40 (5.5 percent) of the 728 unique observations were universal — associated with milestones from all four checklists.

In addition, close to half of the 40 universal observations involved motor skills (such as “the child is able to move easily on their hands and knees”). This left a dearth of consistent observations across socioemotional, language, and cognitive domains. Notably, only 10 percent of the universal observations fell in the socioemotional domain. (These included “engaging in pretend play with other people” and being “shy or anxious with strangers.”)

The expected ages for different behaviors also varied. Of the 40 universal observations, barely half had the same target ages across all four checklists. For example, the CDC’s checklist cited “Dresses and undresses self” at 36 months, whereas the Healthy Children checklist cited “Dresses and undresses without assistance” at 60 months.

Finally, many milestones on the checklists do not specify what percentage of children has acquired a skill by a given age. That makes it difficult for parents and physicians to know when to be concerned.

Parental takeaways

Dr. Wilkinson emphasizes that even the best milestone checklists only indicate a developmental trajectory. Parents should be focused on long-term developmental goals and the big picture of their child’s development, she says, rather than expecting their children to achieve a certain milestone by the exact month specified in a checklist.

“It’s really about a child’s trajectory and following them over time and making sure that they’re making progress in skills, rather than asking whether they have a skill at an exact time point,” she says. “Every child develops at a different speed and that’s one of the reasons why it’s difficult for the checklists to be accurate.”

Despite the shortcomings of checklists, Dr. Wilkinson acknowledges their importance in providing easily accessible information about child development. However, she worries that the milestone inconsistencies “might either be causing parents unneeded anxiety when they think their child isn’t meeting a milestone, or a missed opportunity to identify a delay early on because of false reassurance.”

Ultimately, Dr. Wilkinson hopes this research will empower parents to be more vocal about their child’s developmental health in well-child visits. Children should receive a formal developmental assessment at their 9-, 18-, and 24-month visits.

It’s really about following a child over time and making sure that they’re making progress in skills, rather than asking whether they have a skill at an exact time point.

“Then they can ask their pediatrician, ‘Hey, I think we’re due for a screener, I want to make sure we do it.’ That’s how physicians really will be able to identify whether a child has a delay or not.”

Standardizing milestones

Dr. Wilkinson still hopes to create a consistent, standardized list of developmental observations that could easily be included in a patient’s EHR. Such a list would help practitioners and parents focus on how they can help their child thrive.

“Then we can begin to say, ‘Your child is going to be working on these things for the next six to nine months, here’s how you can help them,’” she says.

Eventually, she hopes this can occur nationally.

A better understanding of what increases a child’s risk for developmental delays could help physicians reduce that risk, Dr. Wilkinson adds.

“If you had something that was integrated into EHRs across the country, you could do really large-scale data analysis and ask, ‘Across the country, which has such a large, diverse population, when do milestones on average occur? Do delays in specific milestones predict more significant delays later on?’”

The study was published online in the Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. Dr. Wilkinson was the first author.

Watch the video abstract delivered by Dr. Wilkinson to learn more.

Related Posts :

-

Medical care for youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A call for change

According to national data, one in six children has a neurodevelopmental disability (NDD) such as autism, intellectual disability, or ADHD. ...

-

BRD7 research points to alternative insulin signaling pathway

Bromodomain-containing protein 7 (BRD7) was initially identified as a tumor suppressor, but further research has shown it has a broader role ...

-

When diagnosis is just the first step: The Brain Gene Registry

Through advances in genetic sequencing, many children with rare, unidentified neurodevelopmental disorders are finally having their mysteries solved. But are ...

-

Engineered cartilage could turn the tide for patients with osteoarthritis

About one in seven adults live with degenerative joint disease, also known as osteoarthritis (OA). In recent years, as anterior ...