How COVID-19 triggers massive inflammation

Why do some people with COVID-19 develop severe inflammation, leading to respiratory distress and damage to multiple organs? A new study in the journal Nature provides an explanation: the SARS-CoV-2 virus infects and kills critical immune cells in the blood and lungs, which set off powerful alarm bells as they die.

Judy Lieberman, MD, PhD, and Caroline Junqueira, PhD, in Boston Children’s Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine led the study with Michael Filbin, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“We wanted to understand what distinguishes patients with mild versus severe COVID-19,” says Lieberman. “We know that people with severe disease have elevated inflammatory markers, and that inflammation is at the root of disease severity. But we hadn’t known what triggers the inflammation.”

A fiery death of immune cells

The researchers analyzed fresh blood samples from patients with COVID-19 coming to the emergency department at Massachusetts General Hospital. They compared these with samples from healthy people and patients with other respiratory conditions. They also looked in lung autopsy tissue from people who died from COVID-19.

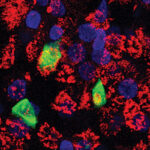

The team found that SARS-CoV-2 can infect two types of immune cells that act as “sentinels” or early responders to infection: monocytes in the blood and macrophages in the lungs. Once infected, the cells die a fiery death called pyroptosis. As they flame out, they release an explosion of powerful inflammatory alarm signals.

“About 6 percent of the blood monocytes in the infected patients were dying an inflammatory death,” says Lieberman. “That’s probably an underestimate, because the body rapidly eliminates dying cells.”

A similar fiery death was unfolding in about a quarter of macrophages from the lung tissue of those who died from COVID-19.

The fact that SARS-CoV-2 can even infect monocytes and macrophages was a surprise. Monocytes don’t carry ACE2 receptors, the usual entry portal for the virus, and macrophages have low amounts of ACE2. Yet Lieberman’s team found that about 10 percent of monocytes and 8 percent of lung macrophages were infected.

The good news was that the virus did not replicate in infected immune cells. The researchers believe the cells died quickly from pyroptosis before new viruses could fully form.

“In some ways, uptake of the virus by these ‘sentinel’ cells is protective. It sops up the virus and recruits more immune cells,” says Lieberman. “But the bad news is that all these inflammatory molecules get released. In people who are prone to inflammation, such as the elderly, this can get out of control.”

Could antibodies facilitate infection?

In another twist, the study found evidence that the antibodies people with COVID-19 develop may actually encourage infection and inflammation.

Lieberman and her colleagues noticed that all of the infected monocytes carried a receptor called CD16. Cells with CD16 usually make up only about 10 percent of all monocytes. But in patients with COVID-19, their numbers were increased, and about half of them were infected.

In some ways, uptake of the virus by these ‘sentinel’ cells is protective. It sops up the virus and recruits more immune cells. But the bad news is that all these inflammatory molecules get released.”

The team then found that the antibodies people make against the virus’s spike protein attach to CD16 receptors. Paradoxically, this helps the virus get into blood monocytes. “The antibodies coat the virus,” Lieberman explains. “Then cells with the CD16 receptor take up the virus.”

In theory, this suggests that the antibodies we make to fight COVID-19 can actually worsen inflammation. More reassuringly, the team found that antibodies healthy people made in response to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines did not facilitate infection of monocytes in the lab. Lieberman thinks that antibodies generated by the vaccine don’t attach as well to CD16 receptors. As a result, when vaccinated people are exposed to COVID-19, their monocytes may not take the virus up, so they are protected.

Potential implications for monoclonal antibody treatment

Lieberman and her colleagues believe their findings could have implications for using monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19, helping to explain why the treatment works only when given early.

“The antibodies block infection of lung cells, which are where the virus reproduces, but they can also promote infection of immune cells, increasing inflammation,” Lieberman says. “We may need to look more closely at the properties of the antibodies that promote infection of monocytes and macrophages, which appears to be responsible for the out-of-control inflammation in severe COVID-19.”

Caroline Junqueira, PhD, Ângela Crespo, PhD, and Shahin Ranjbar, PhD, in Boston Children’s Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine were co-first authors on the paper.

Learn more about COVID-19 research at Boston Children’s

Related Posts :

-

A respiratory model of COVID-19, made from patients’ own cells

What happens in our respiratory tract once COVID-19 invades? A three-dimensional airway model, made from patient-derived stem cells, could provide ...

-

From our labs and clinics: The top 10 COVID-19 science stories of 2021

As COVID-19 waxed, waned, morphed, and waxed again this year, research was taking place throughout Boston Children’s Hospital. Ongoing ...

-

New research NETs a fresh angle for treating severe inflammation

As we’ve seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, serious infections sometimes trigger an excessive inflammatory reaction that does as much ...

-

Unpacking the body’s interferon response to COVID-19

Interferons are potent natural antivirals, rallying other parts of the immune system to defend against viruses. Some clinical trials have ...