Gasdermin E: A new approach to cancer immunotherapy

Tumors have figured out various ways to prevent the immune system from attacking them. Medicine, for its part, has fought back with cancer immunotherapy. The major approach uses checkpoint inhibitors, drugs that help the immune system recognize cancer cells as foreign. Another method, CAR T-cell therapy, directly engineers peoples’ T cells to efficiently recognize cancer cells and kill them.

But other options are sorely needed. Current cancer immunotherapies work for just a minority of cancer types, and CAR T-cell therapy carries significant risks. New research from Boston Children’s Hospital, published today in Nature, adds another strategy to the arsenal, one that could potentially work in more types of cancer.

When you reactivate gasdermin E in a tumor, it can convert an immunologically ‘cold’ tumor into a ‘hot’ tumor that the immune system can control.”

The new approach harnesses an immune response we already have but that is suppressed in many types of cancer. It works by reactivating a gene called gasdermin E.

“Gasdermin E is a very potent tumor suppressor gene, but in most tumor tissues, it’s either not expressed or it’s mutated,” says Judy Lieberman, MD, PhD, of the Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine (PCMM), the study’s principal investigator. “When you reactivate gasdermin E in a tumor, it can convert an immunologically ‘cold’ tumor — not recognized by the immune system — into a ‘hot’ tumor that the immune system can control.”

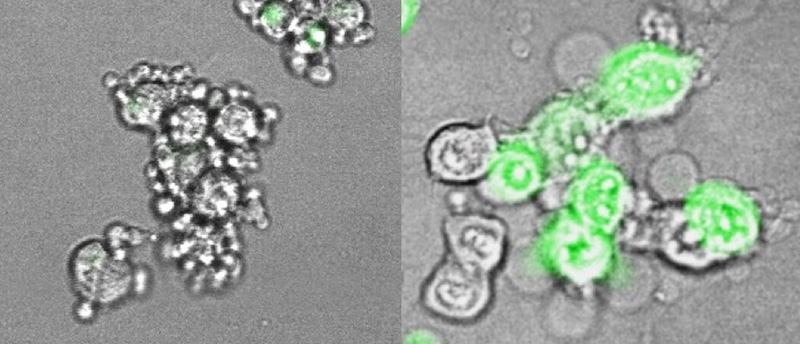

In the study, Lieberman and colleagues showed that 20 of 22 cancer-associated mutations they tested led to reduced gasdermin E function. When they re-introduced gasdermin E in a mouse model, they were able to trigger pyroptosis and suppress growth of variety of tumors (triple-negative breast tumors, colorectal tumors, and melanoma).

Heating up the immune response to cancer

The team also showed, in mouse tumor cell lines, how gasdermin E works. Normally, when cells die, including most cancerous cells, it’s through a process called apoptosis, a quiet, orderly death. But if gasdermin E is present and working, cancer cells go down in flames, through a highly inflammatory form of cell death called pyroptosis.

As Lieberman’s team showed in live mice, pyroptosis sounds a potent immune alarm that recruits killer T cells to suppress the tumor. The team is now investigating therapeutic strategies for inducing gasdermin E to rally that anti-tumor immune response.

“What we’re suggesting is that if we can turn on the danger signal, which is inflammation, we can activate lymphocytes more fully than with other immunotherapy approaches, and have immunity that is potentially much broader,” says Lieberman. “Combining activation of inflammation in the tumor with approved checkpoint inhibitor drugs could work better than either strategy on its own.”

Companies interested in collaborating with the scientists to further the research in this area should contact the Boston Children’s Technology and Innovation Development Office at TIDO@childrens.harvard.edu.

Zhibin Zhang, PhD, and Ying Zhang, PhD in the Lieberman lab were co-first authors on the paper in Nature. and Hao Wu, PhD, of PCMM was a collaborator. The study was supported by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility, NIH R01 AI139914, a Charles A. King Trust Fellowship, and a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Breakthrough Fellowship Award.

More from the Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine

Related Posts :

-

Building better antibodies, curbing autoimmunity: New insights on B cells

When we’re vaccinated or exposed to an infection, our B cells spring into action, churning out antibodies that are ...

-

Exposing a tumor’s antigens to enhance immunotherapy

Successful immunotherapy for cancer involves activating a person’s own T cells to attack the tumor. But some tumors have ...

-

Combining CAR-T cells and inhibitor drugs for high-risk neuroblastoma

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy is a potent emerging weapon against cancer, altering patients’ T cells so they ...

-

Could a GI bug’s toxin curb hard-to-treat breast cancer?

Clostridium difficile can cause devastating inflammatory gastrointestinal infections, with much of the damage inflicted by a toxin the bug produces. ...