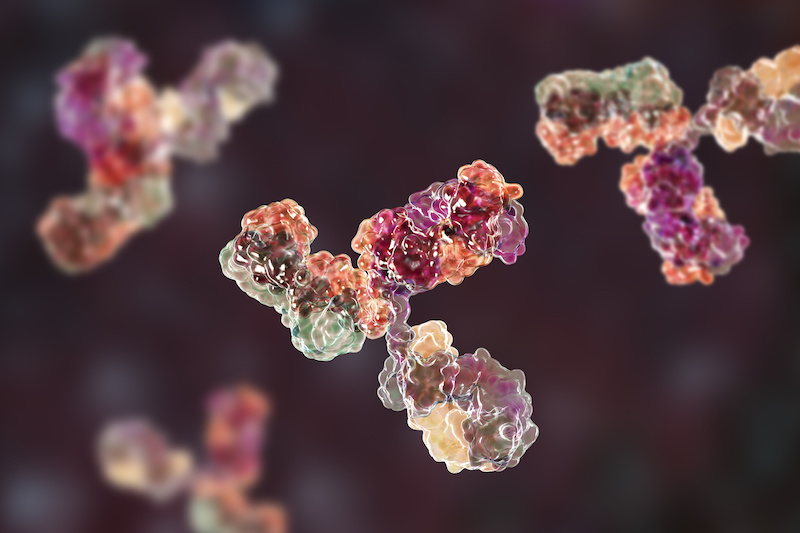

How new loops in DNA packaging help us make diverse antibodies

Diversity is good, especially when it comes to antibodies. It’s long been known that a gene assembly process called V(D)J recombination allows our immune system to mix and match bits of genetic code, generating new antibodies to conquer newly encountered threats. But how these gene segments come together to be spliced has been a mystery. A new study in today’s Nature provides the answer.

Our DNA strands are organized, together with certain proteins, into a packaging called chromatin, which contains multiple loops. When a cell needs to build a particular protein, the chromatin loops bring two relatively distant DNA segments in close proximity so they can work together. Many of these loops are fixed in place, but cells can sometimes rearrange loops or make new loops when they need to — notably, cancer cells and immune cells.

The new research, led by Frederick Alt, PhD, director of the Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine (PCMM) at Boston Children’s Hospital, shows in exquisite detail how our immune system’s B cells exploit the loop formation process for the purpose of making new kinds of antibodies.

Scanning loops as they form

As the researchers show, a pair of enzymes called RAG1 and RAG2 couple with mechanisms involved in making the chromatin loops to initiate the first step of V(D)J recombination: joining the D and J segments. First, the RAG 1/2 complex binds to a site on an antibody gene known as the “recombination center.” Next, as the DNA scrolls past during the process of loop formation (“extrusion”), the RAG complex scans for the D and J segments the cell wants to combine. Then, other factors impede the extrusion process, pausing the scrolling DNA at the recombination center so that RAG can access the desired segments.

“Antibody gene loci harness the loop extrusion process to properly present substrate gene segments to the RAG complex for V(D)J recombination,” says Alt.

Many of the hard-wired chromatin loops are formed and anchored by a factor called CTCF. But the Alt lab shows that other factors are involved in dynamic situations, like antibody formation, that require new loops on the fly. The study also establishes the role of a protein called cohesin in driving the loop extrusion/RAG scanning process.

“While these findings have been made in the context of V(D)J recombination in antibody formation, they have implications for processes that could be involved in gene regulation more generally,” says Alt.

Yu Zhang, PhD, of the PCMM was the study’s first author. She is now at the Western Michigan University Homer Striker M.D. School of Medicine. The work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

More on this topic, and more from PCMM

Related Posts :

-

Building better antibodies, curbing autoimmunity: New insights on B cells

When we’re vaccinated or exposed to an infection, our B cells spring into action, churning out antibodies that are ...

-

Exposing a tumor’s antigens to enhance immunotherapy

Successful immunotherapy for cancer involves activating a person’s own T cells to attack the tumor. But some tumors have ...

-

Could we intervene in Huntington’s disease before symptoms appear?

Huntington’s disease is the most common single-gene neurodegenerative disorder and is characterized by motor and cognitive deficits and psychiatric ...

-

Could the right dietary fat help boost platelet counts?

Aside from transfusions, there currently is no way to boost people’s platelet counts, leaving them at risk for uncontrolled ...