Inspired by Chinese finger traps, an annuloplasty ring that grows with the child

This post is part of a series on innovations to treat valvular disease in children. Read our prior posts on transcatheter valve replacement and an expandable prosthetic heart valve.

Prosthetic annuloplasty rings have improved the durability of heart valve repairs in adults. Implanted at the perimeter of dilated, leaky valves, they help keep the valve opening at its normal size. But these rings cannot be used in children, whose hearts and valves are still growing.

“Valve pathology is a problem with significant consequences and no clear solution in children,” says Eric Feins, MD, a cardiac surgeon in the Heart Center at Boston Children’s Hospital. “Annuloplasty rings for adults, which come in a fixed size, have shown benefit. But you can’t fit a ring for a 2-year-old and expect it will still work when they’re 15.”

Many pediatric cardiac surgeons use sutures to cinch leaking mitral and tricuspid valves. However, that is only a temporary solution. Most children must endure repeat operations to re-repair or replace the leaking valves. Unfortunately, valve replacement entails risk and decreased survival for children.

In Nature Biomedical Engineering in 2017, Feins and his colleagues described an annuloplasty ring that expands as a child grows. Through a partnership with the hospital’s Drug, Device, Diagnostics Accelerator (D3A), Feins now aims to bring the device to clinical trials.

A self-elongating ring

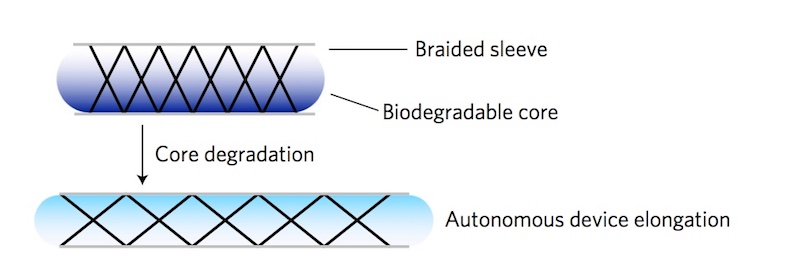

Feins originally developed the expandable ring design as a research fellow in the lab of Pedro del Nido, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Boston Children’s, together with bioengineers Yuhan Lee, PhD, and Jeffrey Karp, PhD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The ring’s stretchy, braided design, enabling the device to elongate as a child grows, was inspired by Chinese finger traps.

“The design consists of two principle components that work together: a degradable, biopolymer core and a braided, tubular sleeve that elongates in response to tensile forces exerted by the surrounding growing tissue,” says Feins. “As the inner biopolymer degrades, the sleeve naturally becomes thinner and elongates as the tissue grows.”

The team’s first proof-of-concept was a tricuspid valve annuloplasty ring implant. Feins believes its simplicity — with few moving parts that could fail or break down — adds to its durability inside a beating heart.

The inner biopolymer, made of biocompatible materials, can be fine-tuned to degrade at different rates. This allows the sleeve to elongate at the ideal rate for the child’s age. “This was somewhat counterintuitive: device growth secondary to device degradation,” Feins wrote in an essay in Nature.

Gearing up for clinical testing

With this proof-of-concept in hand, Feins and his colleagues are working with William Clarke, MD, and Mei Mei Huang, MBA, PhD at D3A to determine the best regulatory approach to getting the device through the FDA approval process. That will likely entail additional large-animal experiments, mechanical testing, and product development work with device manufacturer Medical Murray to adapt the ring for commercial production and use. The goal is an early feasibility study in children, followed by a small clinical trial.

“Having compelling in vivo animal data is just the beginning of the journey,” says Feins. “The heavy lifting comes when you try to bring a device to market so it’s helping kids.”

Feins isn’t the only cardiac surgeon at Boston Children’s looking to improve options for pediatric valve disease. Our next article in the series will focus on the Ozaki procedure, which crafts a new heart valve from the patient’s own tissue, spearheaded at Boston Children’s by del Nido and Christopher Baird, MD, director of the Heart Valve Program.

Learn more about Boston Children’s Heart Valve Program

Related Posts :

-

Someday, this prosthetic heart valve might be the only one a child needs

More than 330,000 children worldwide are born with a heart valve defect, and millions of others develop rheumatic heart disease requiring ...

-

Two decades of innovation in pulmonary vein stenosis

Over the past 20 years, the Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Program at Boston Children’s Hospital has been crafting an ...

-

Coordinated care and research for genetic cardiovascular disorders

Genetic cardiovascular disease in children sometimes comes to light in a crisis — a sudden collapse, sudden breathing difficulty, a sudden ...

-

Innovations in transcatheter valve replacement

The Cardiac Catheterization Program at Boston Children’s Hospital has been at the cutting edge of pediatric care for more ...