Knowing what life is worth: I am an adult heart patient and much more

Most of the children showed off a favorite toy. Some brought items that were meaningful to their family or culture. When I got to the front of my kindergarten class, my hands were empty.

“My show-and-tell is…me,” I exclaimed as I pulled up my shirt and bared my chest to an audience of shocked five-year-olds and one shocked teacher. I explained that when I was a baby, I underwent surgery to fix a problem with my heart. Though I did not remember the surgery, I had a big scar on my chest where the doctors had opened me up.

This is one of my earliest memories. Even then, I defined myself in terms of my heart disease.

Needing care for several heart conditions

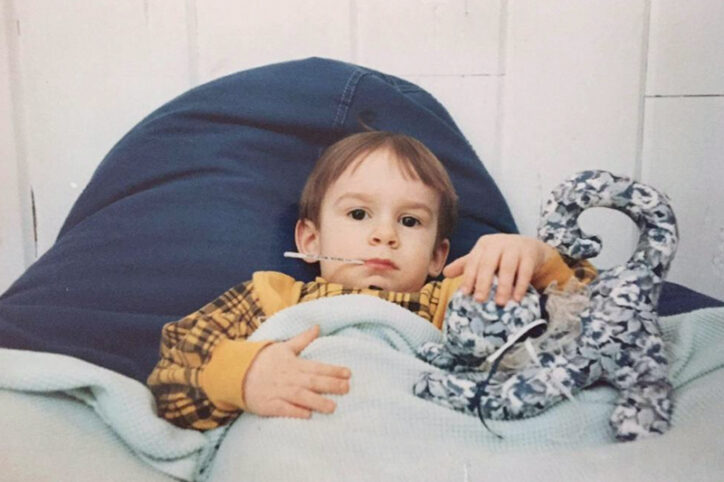

I was born with the rare condition tetralogy of Fallot (ToF), a group of four congenital heart defects (CHDs) that prevents the necessary amount of blood from being oxygenated in the lungs. Luckily, I was born at a time when surgery to treat ToF was common in infants. At 6 months old, my heart was repaired, allowing me to live a relatively normal childhood, besides the occasional locker room question about the scar running down my chest.

As I grew older, though, my heart’s performance didn’t keep up. When I was 19, doctors detected a dangerous heart rhythm: a condition known as monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. I started taking beta blockers to prevent runaway heartbeats, and the next year I underwent open-heart surgery to replace my pulmonary valve.

Just as importantly, I started receiving regular care from Dr. Anne Marie Valente, a cardiologist at the Boston Adult Congenital Heart (BACH) and Pulmonary Hypertension Program. I love Dr. Valente. She has a great bedside manner and is interested in me as a person. I’ve been seeing her for the past 13 years, and the wonderful care she provides hasn’t changed.

Being ‘more than a heart patient’ is challenging

The most meaningful advice Dr. Valente gave me came early on. She thought it was great that I was pushing myself physically and academically. It gave her the opportunity to say that I should never think of myself as a heart patient. Rather, I could live like any other person. Sure, I had this little heart thing, but I shouldn’t let that limit what I did or how I viewed myself.

The truth is, having a chronic health condition can feel limiting. When I have to shave my chest to wear a Holter monitor for a week; when I have to run on a treadmill wearing a gas exchange mask and EKG leads; when I am jolted by a sudden palpitation while sitting at my desk; or when I am rolled into the cardiac catheterization lab to have another pulmonary valve replacement inserted — I sure do feel like a heart patient. And beneath that feeling has often lurked something more painful: the belief that because of the body I have, I am destined to live a “worse” life than the average person.

It is easy for this kind of attitude to fester. I didn’t realize how easily I had adopted this negative perception until I read a pamphlet about quality of life and congenital heart disease. It is believed that those with heart disease have a lower quality of life because of physical limitations and the uncertainty of chronic disease. However, the pamphlet pointed out that quality of life can also mean how satisfied a person is with their life. In fact, those with heart disease can often have a better quality of life than healthy people.

This isn’t just wishful thinking; studies have shown just that. The phenomenon of people with major physical limitations reporting good or excellent life satisfaction is known as the disability paradox. That’s the thing: Quality of life comes down to self-perception, context, and relationships. Sure, a chronic disease can make life feel hopeless at times. Many adults with heart disease, including myself, have had to work to manage anxiety and depression.

But living with heart disease can also give life clarity and meaning. Because they grow up with heart disease, many heart patients can develop values that are different from “healthy” people. Heart patients recognize what life is worth; little things don’t bother them.

Appreciating the scary and sublime of life

Reading those words helped me appreciate how my heart conditions have given me a high quality of life. It made me remember how my second heart surgery forced me to assess my values and goals. I was then studying social sciences and humanities without clear direction, but after surgery, I decided to pursue engineering to help others with physical limitations. Today, I’m closer to my dream: I am pursuing a PhD in biomechanics and assistive technology. I also recently started an internship with Apple’s health technologies team, working to develop new sensors that can help people detect and monitor underlying conditions.

Yes, I am a heart patient, but I am much more than that. I am also a researcher, runner, rock climber, reader, pianist, improv comedian, musical theater nerd, roller coaster lover, skier and snowboarder, coder, cook, crossword puzzle enthusiast, world traveler, “Jeopardy!”devotee, husband, brother, uncle, and friend.

My heart condition can slow me down sometimes, but it is also a nondepletable source of motivation. Often, life can be stressful, uncertain, and scary! But, just as often, it is rewarding, beautiful, precious, and sublime. By focusing on how I do the things within my control — with gratitude, humor, and a sense of purpose — I’ve learned to live a “high-quality” life on my own terms.

Learn more about the Boston Adult Congenital Heart (BACH) and Pulmonary Hypertension Program.

Related Posts :

-

A lifetime of treatment inspires Ruth to advocate care for others

Ruth Ngwaro offers guidance to children who have heart disease. Perhaps her most useful bit of advice is telling them ...

-

Kiersten finds new purpose after care for life-threatening cardiomyopathy

Being just three miles away from her cardiac care team at Boston Children’s makes all the difference in the ...

-

Letters from the heart: “Life will be better”

Children with congenital heart disease (CHD) have much to think about as they undergo tests, try medications, and face possible ...

-

Ted Williams, chocolate milkshakes, and a pioneering heart team: What Bruce remembers about his heart surgery 65 years later

Bruce Chansky was the star of his neighborhood after he had heart surgery at Boston Children’s. It was 1959, a ...