Gene therapy with a new base editing technique restores hearing in mice

Using a new genetic engineering technique, known as base editing, researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, have restored hearing in mice with a known recessive genetic mutation.

· This is the first example of repairing a recessive gene mutation.

· Repairing a single mutation in the Tmc1 gene restored partial hearing in mice.

· This technique opens the door to treating other genetic forms of hearing loss and other genetic diseases.

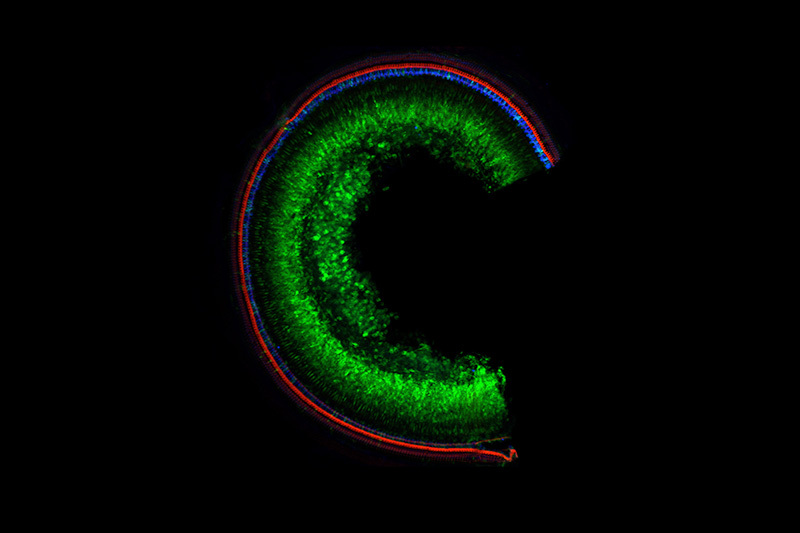

With this technique, the team repaired one single error in the Tmc1 gene known to cause a hereditary form of deafness. The one-time repair involved switching one incorrect DNA base in the gene with the correct version. While a similar approach has been used previously for other forms of hearing loss, this is the first time base editing has been used for a genetic sensory disorder. Details about the approach are published in a new paper in Science Translational Medicine.

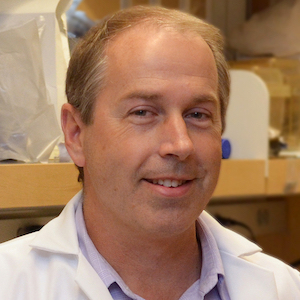

“This research is very important for the pediatric community here at Boston Children’s Hospital and elsewhere because about 4,000 babies are born each year with genetic hearing loss,” says Jeffrey Holt, PhD, director of otolaryngology research at the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, co-senior author on the study with David Liu, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. “And, we feel this is a big step beyond the field of hearing restoration and for the broader field focused on treatment of genetic disorders.

Base editor acts as a spell-check

Earlier research in 2015 from the Holt lab and colleagues showed that replacing a full DNA sequence for Tmc1 into the sensory cells in the ear restores hearing in deaf mice.

“In that case, we used a single engineered adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver a functioning copy of the Tmc1 gene into the ear,” he says.

This research goes a step further. Instead of replacing a gene, the team repaired a single mutation in the Tmc1 gene converting it back to the correct sequence. “It’s like your spell checker,” he says. “If you type the wrong letter, spell checker fixes it for you.” When the team fixed the defect in the sensory cells in the ear, within four weeks the edited cells recovered 100 percent of their function.

But the base editor was too large for a single AAV. The newly designed base editor that engineers the genetic repair required more space. It did not fit into a single AAV. Instead, they split up the base editor sequence into two AAVs.

“Once the cell was infected with these two parts, it reassembled into a single full length sequence and performed the base editing task we needed,” says co-first author Olga Shubina-Oleinik, PhD, of the Holt lab.

It is important to note the approach worked when both AAVs made their way into the cell. But that was the case in about one-quarter of the cells which was enough to provide some hearing to the mice.

“We got it to work but we need to boost the efficiency to make it broadly useful,” says Holt. If only one AAV got into the cell, it did not work. “But the message is that when we got both into the cells, we went from zero function to 100 percent. That tells me all we need to do is get it into more cells and we will recover more hearing function.”

Building on previous success

At least 100 different genes have a role in hearing in the inner ear. Mutations in any one of those can lead to hearing loss.

We hope this new technique will allow us to treat these mutations one at a time to restore hearing and balance related to the inner ear.”

Jeffrey Holt

“We have been developing different strategies targeting several of these different forms of hearing loss,” says Holt. “We take a precision medicine approach where we tailor our strategy specifically, not just on the gene that is involved, but the individual genetic mutation in the gene.”

The Holt lab has a long history of success unraveling these genetic causes of hearing loss and developing gene therapy treatments for genetic forms of hearing loss. In 2011, the team first discovered that the Tmc1 protein is required for hearing and balance. After its 2015 success, the Holt team used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in 2019 to prevent hearing loss in Beethoven mice, a model of a dominant Tmc1 mutation.

Just one of many mutations related to hearing and balance

Over 70 different mutations have been identified in the Tmc1 gene in humans. “We hope this new technique will allow us to treat these mutations one at a time to restore hearing and balance related to the inner ear,” says Holt.

Along with hearing loss, balance disorders represent a large unmet medical need, though it is present mainly in aging adults. The inner ear houses the cochlea (the auditory organ) and five organs of balance — the vestibular organs. Disruptions in function in any of those five could lead to balance problems.

Other contributors to this research include Olga Shubina-Oleinik and Bifeng Pan of Boston Children’s Hospital; Wei-Hsi Yeh, Jonathan Levy, Gregory Newby, Michael Wornow, and Jonathan Chen of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; and Rachel Burt of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Australia.

Grants from the US National Institutes of Health, the Harvard Hughes Medical Institute, the Jeffrey and Kimberly Barber Fund, and the Foundation Pour L’Audition supported this research.

Read more about the Holt’s lab progress in gene editing for hearing loss

Related Posts :

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, then a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity ...

-

The dopamine reset: Restoring what’s missing in AADC deficiency

In March 2023, a young girl came to Boston Children’s Hospital unable to hold up her head — one striking symptom ...

-

Mark’s winning pass with cochlear implants

Mark Bradshaw wanted to break out of his parents’ protective shell — as many teens do when they start pushing for ...

-

A sickle cell first: Base editing, a new form of gene therapy, leaves Branden feeling ‘more than fine’

Though he doesn’t remember it, Branden Baptiste had his first sickle cell crisis at age 2. Through elementary school, he ...