A case for Kennedy — and for rapid genomic testing in every NICU

Kennedy was born in August 2025 after what her parents, John and Diana, describe as an uneventful pregnancy. Soon after delivery, though, she struggled to breathe and feed. What followed was a series of hospital stays, a complex diagnosis, and a glimpse into how rapid genomic testing can deliver answers that guide critical decisions and potentially transform NICU care.

A rare condition, rapid answers

Within days of her birth, Kennedy was transferred from her local hospital in New Hampshire to a larger regional medical center, where doctors diagnosed her with pyriform aperture stenosis (PAS), a rare condition that narrows the nasal passages. Recognizing she needed specialized otolaryngology care, the team transferred her to Boston Children’s Hospital, where she was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for evaluation.

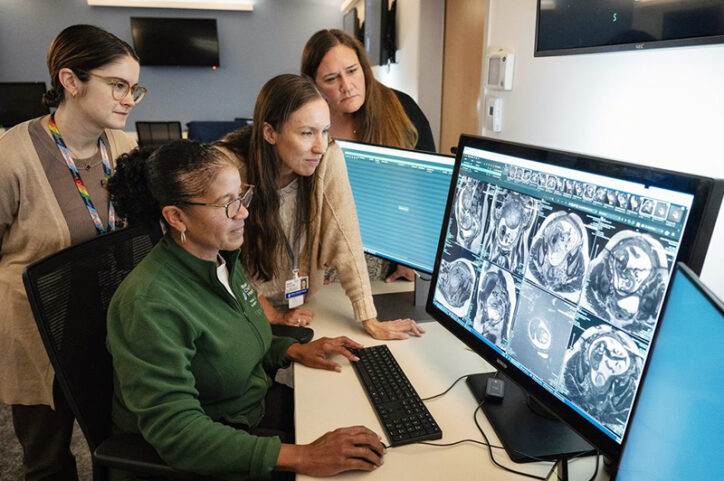

Her arrival at Boston Children’s came at an opportune time — just as Dr. Monica Wojcik, director of the Neonatal Genomics Program, genetic counselor Gwendolyn Strickland, and the rest of the Neonatal Genomics team were launching their Seq4NICUs study, a rapid whole genome sequencing protocol to identify potential genetic conditions in infants that might otherwise go undetected. Their goal: to improve access to timely diagnostics for all families. Unlike general genetic testing, which looks for a small number of known gene changes, genomic sequencing provides a more comprehensive view and broader insight into potential causes of unexplained conditions by reading a person’s full genetic makeup.

Why rapid testing matters

Historically, genomic sequencing has been slow, costly, and limited to patients showing specific symptoms, such as muscle weakness, seizures, and congenital anomalies. But within the last 10 years, rapid genome testing — which can deliver results in days instead of months — has become more widely adopted, especially in higher-acuity NICUs caring for the most critically ill infants. However, many NICUs still use an “opt-in” or selective model, offering genetic testing only to infants who show clear signs of a genetic condition and where the diagnosis is likely to influence NICU care. This approach can miss cases. In contrast, a universal approach to sequencing offers rapid genomic testing to every infant in the NICU, regardless of their reason for admission. “Some symptoms that seem like they’re due to prematurity or infection [two leading causes for admittance to a NICU] might actually have a genetic cause; or we may suspect a genetic condition but defer the actual testing to after NICU discharge.” Wojcik says. “But the NICU is a pivotal window of time for diagnosis.”

Kennedy’s tests came back within a week and revealed SOX6 syndrome, an extremely rare and complex genetic condition that can be associated with developmental delays, unique facial features, and abnormal skull development. Fewer than two dozen cases of SOX6 syndrome have been identified globally. Kennedy’s additional presentation of PAS may be the first of its kind ever reported in connection with the syndrome.

“We don’t know a whole lot about SOX6,” John says. “But Kennedy’s case might help her doctors and researchers learn more.”

Wojcik says it’s this collaborative mindset that’s at the heart of the universal sequencing approach: building knowledge case by case together with NICU families, so that eventually rare conditions become better understood and more treatable.

Addressing equity and long-term outcomes

Universal sequencing availability also addresses a persistent challenge in health care: inequity in access to diagnostic testing. A 2022 study by Wojcik and colleagues shows families facing barriers to health care often struggle to attend genetics clinic appointments, making it harder to continue genomic care after NICU discharge. By offering testing to all undiagnosed infants while they’re in the NICU, universal rapid sequencing aims to level the playing field, helping families plan and connect with support, and enabling doctors to tailor care while avoiding unnecessary tests.

In Kennedy’s case, receiving her diagnosis early has allowed her care team to monitor for other potential complications associated with SOX6. John and Diana are arranging feeding therapy and early intervention services near their home in New Hampshire while remaining in close contact with the genetics and ENT teams at Boston Children’s.

Kennedy is now 2 months old and thriving at home. “She’s doing really well,” says Diana. “She has to work hard to feed, but she’s off the feeding tube and gaining weight. She’s very snorty, but she’s very cute.”

Looking ahead to a new standard of care

Wojcik and team continue to evaluate how universal access to genomic sequencing could be implemented on a larger scale, with the hope that if more NICUs adopt the model, rapid genomic sequencing could become a standard aspect of care for every infant who needs it.

For John and Diana, the ability to get answers quickly, connect with specialists, and contribute to life-changing research has had a profound impact.

“Kennedy’s given us the chance to help others,” says John. “If her story helps just one other family, it’s worth it.”

Learn more about neonatal genetic testing at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Related Posts :

-

A legend for Zora: How genomic testing provides answers in the face of grief

So often after a perinatal loss, parents are left with uncertainty about what caused their baby’s death and the ...

-

Bringing genomics to community NICUs

About a year and a half ago, Robert Rothstein, MD, FAAP encountered a baby with a pattern of facial features ...

-

Making genome sequencing a first-line test in rare disease

Children with rare diseases often undergo years of medical visits and genetic testing before they get a diagnosis. Over the ...

-

I’ve been there, too: What my baby’s tumor taught me as a NICU nurse

I had a toddler at home when I found out I was pregnant with my twins, Hannah and Sophie. Since ...