Ask a sports medicine specialist: Why are ACL tears so common among female athletes?

When an athlete is sprinting after an opponent who suddenly stops or changes direction, their anterior cruciate ligaments (ACLs) make it possible for them to continue their pursuit. This much talked-about ligament is the reason athletes can pivot, cut, jump, and land.

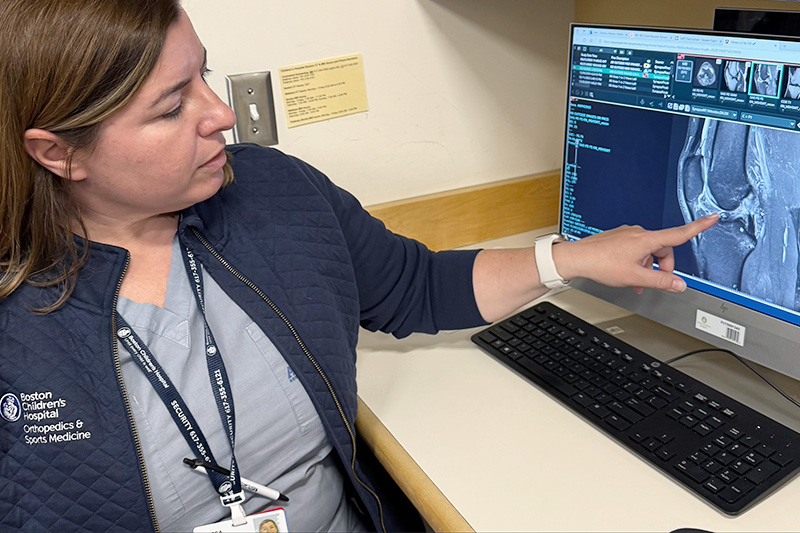

“The ACL is one of the main stabilizing ligaments in the knee,” explains Dr. Melissa Christino of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Program at Boston Children’s Hospital. Vital in a wide variety of sports, athletes’ ACLs are all too often strained to the point of injury.

As female athletes compete at higher levels of play, the number of ACL injuries has increased — affecting female athletes at a rate two to eight times higher than that of male athletes. Not surprisingly, ACL injuries are among the most common injuries Dr. Christino treats in female athletes.

Why are female athletes at such high risk of ACL injury? We asked Dr. Christino for answers.

Which sports have the highest rate of ACL injuries for female athletes?

“Female soccer players have the highest rate of ACL injury,” says Dr. Christino. “But ACL injuries are common in any high-demand sport that involves cutting or pivoting, such as basketball, lacrosse, gymnastics, and competitive cheer — to name a few.”

Why are ACL tears more common in female athletes?

Several factors may contribute to the high rate of ACL injury in female athletes.

“Female athletes typically have a wider-set pelvis,” says Dr. Christino. Because their hips are farther apart, female athletes’ knees are more prone to slant inward, placing the ACL under greater strain.

The structure of the knee may also play a role. Because of their smaller anatomy, the notch that houses the ACL inside the knee is often smaller in women, possibly making the ligament more prone to injury.

In addition, many female athletes’ quadriceps are stronger than their hamstrings, an imbalance that can put uneven pressure on the ACL.

Researchers are also looking into whether female athletes’ joints are looser at a certain stage of the menstrual cycle, and if that could increase their risk of ACL injury.

Do athletes with ACL injuries always need surgery?

Unfortunately, torn ACLs don’t heal on their own, so any athlete who wants to return to high-level sports will likely need surgery. Continuing to play on an unstable knee often damages the knee cartilage further. “The longer a patient waits, the more damage we see,” says Dr. Christino.

In studies, female patients tend to report greater psychological stress and lower readiness to return to sports than male athletes after ACL surgery. However, Dr. Christino cautions, there could be several reasons for this. For instance, female subjects may be more comfortable than males disclosing emotional distress.

What’s the hardest part of recovery?

Recovering after ACL surgery typically involves six to nine months of intense physical therapy and up to a year before an athlete can fully return to their sport without restrictions. As challenging as the physical recovery can be, the emotional impact can sometimes be even more difficult.

“It’s devastating for an athlete to learn they have a torn ACL,” says Dr. Christino.

In her practice and research, she’s found that depression is a common experience for female athletes recovering from a serious injury. Cut off from the rigors of daily training with their team, many feel overwhelmed by negative thoughts, fearing they’ll never be as competitive as they were before their injury.

It’s really important for kids to see other athletes who have gone through injury and recovery, persevered, and overcome adversity to get back to the sports they love.”

Moral support from family and friends during this time is critical. Dr. Christino suggests normalizing the injury, for instance, by citing athletes like Meagan Rapinoe and Candace Parker who came back from ACL injuries to play at the top level.

“It’s really important for kids to see other athletes who have gone through injury and recovery, persevered, and overcome adversity to get back to the sports they love,” says Dr. Christino. Patients of Boston Children’s Sports Medicine Division can also find support through the Sports Behavioral Health Clinic.

Can female athletes reduce their risk of ACL injury?

In many ways, yes.

“When we counsel athletes about ACL injury prevention, we stress the importance of leg strength and good mechanics,” says Dr. Christino. Female athletes can learn safer pivoting and landing techniques that minimize strain on their knees. One way to do so is through The Micheli Center for Sports Injury Prevention, which offers ACL injury prevention classes.

Warming up before practice with running, strengthening, and mobility exercises (such as the FIFA 11+ injury prevention program for soccer) can significantly reduce athletes’ risk of ACL injury. Having a coach who makes injury prevention part of training helps athletes adhere to the program consistently.

And sometimes, avoiding injury is a matter of less work. “Rest is just as important as strength or skills development to keep the body performing well,” says Dr. Christino. Whether recreational or highly competitive, all athletes need time to adequately recover from the stresses of training so they can remain strong and injury free.

Learn more about Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Program, Sports Medicine Division, and Sports Behavioral Health Clinic.

Related Posts :

-

Jackie’s dreams of playing professional soccer back on track after ACL surgery

From her dorm in Newcastle, England, Jackie Zapata can hear fans roaring in the soccer stadium a few blocks away. ...

-

After two ACL tears, a skier reconnects with her body and her sport

The memory remains vivid in Sophia’s mind. Racing down a slalom course at top speed, she hit a patch ...

-

Female athletes and sports injuries: Psychology matters

If the goal of sports medicine is to promote sports participation, the state of an injured athlete’s musculoskeletal system ...

-

Uncertainty surrounds ACL treatment decisions in young athletes. It shouldn’t.

It’s an injury once seen mainly in adults, yet it’s become increasingly common in younger patients. From 2000 to 2020, ...