Unveiling the hidden impact of moyamoya disease: Brain injury without symptoms

Moyamoya disease — a rare, progressive condition that narrows the brain’s blood vessels — leads to an increased risk of stroke and other neurological conditions. Doctors treating children with moyamoya often face difficult decisions about treatment, notably deciding whether to perform revascularization, a surgery to bypass the narrowed blood vessels and restore blood flow. A recent study conducted at the Cerebrovascular Surgery & Intervention Center at Boston Children’s Hospital and published in The Journal of Pediatrics sheds light on the relationship between brain injury and symptoms in children with moyamoya, potentially impacting how doctors approach treating children with asymptomatic moyamoya disease.

What the study found

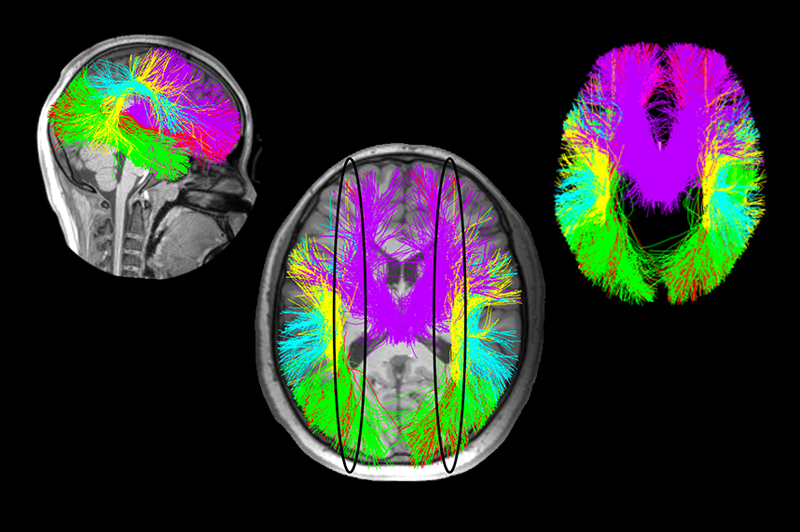

The study, led by Laura Lehman, MD, MPH, aimed to better understand white matter injury in children with moyamoya. White matter plays a critical role in transmitting signals across the brain, and any damage to it can significantly impair brain function. To explore this, the team compared 17 children with moyamoya disease to 27 children without, using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) to assess four key indicators of brain damage. dMRI is a specialized MRI that tracks the movement of water in the brain’s white matter. It helps detect areas where tissue is disrupted, indicating potential brain damage. This technique can uncover subtle injuries that may not show up on regular scans, even in children without obvious symptoms such as stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), and seizures.

The Boston Children’s team used dMRI to track four key indicators:

- Fractional Anisotropy (FA): This reflects the organization of white matter; higher FA values generally indicate healthier tissue.

- Mean Diffusivity (MD): This measures the movement of water within the brain. Elevated MD can signal tissue damage.

- Radial Diffusivity (RD) and Axial Diffusivity (AD): These measure the damage to brain fibers in different directions.

The results showed that both symptomatic and asymptomatic hemispheres in children with moyamoya exhibited higher levels of mean diffusivity than the control group, consistent with white matter injury. Notably, there was no significant difference in the damage between hemispheres with and without symptoms, indicating that even children without signs of stroke, TIA, migraine, or seizures may still be experiencing white matter injury.

“Our findings challenge the assumption that the presence of symptoms is the best indicator of moyamoya’s severity,” says Lehman. “Children without symptoms might still be at risk for significant white matter injury, and our findings open the door to reevaluating how these children are treated.”

What’s next?

The team’s next step is to investigate the effectiveness of revascularization surgery in children with asymptomatic moyamoya. This is important because current approaches for treating children with asymptomatic moyamoya vary, with some physicians opting for medical management alone and others recommending surgery. The team hopes to provide clearer guidance about the best treatment approaches by further examining how revascularization surgery affects children with asymptomatic moyamoya.

As part of the study, they’ll keep using advanced MRI techniques like dMRI to track white matter injury as a potential marker of disease progression. This could give doctors a clearer view of brain damage, even when there are no symptoms, helping them provide more personalized and timely treatments for children with moyamoya.

What does this mean for patients, families, and clinicians?

For parents and caregivers, it can be challenging to grasp how a child who looks and feels healthy might be silently dealing with brain injury. This study brings hope for better diagnosis and more effective treatment, even before symptoms appear. In addition, the ongoing research at Boston Children’s provides an opportunity for patients to participate in studies exploring medical and surgical treatment for children with asymptomatic moyamoya, helping better understand the long-term implications of the disease and shape future treatment.

For clinicians, these insights may help them reconsider how they approach treatment decisions — especially for asymptomatic patients — and ensure that they aren’t missing early signs of serious brain damage. “Our goal,” says Lehman, “is to provide families and our clinical colleagues more precise, evidence-based recommendations that better address the complexities of this rare and serious disease.”

Learn more about the study published in The Journal of Pediatrics or refer a patient to the Cerebrovascular Surgery and Interventions Center.

Related Posts :

-

Groundbreaking research identifies noninvasive biomarker for moyamoya in children

Moyamoya is a rare blood vessel condition that has an outsized impact on children, as it is responsible for about 6 ...

-

New technique designed specifically for children gives surgeons another moyamoya treatment option

Moyamoya is rare blood vessel condition that is a major cause of pediatric stroke. Surgical revascularization can be very effective; ...

-

Optimal care, lower costs: Examining the benefits of out-of-network care for pediatric moyamoya

Moyamoya disease is a rare condition that affects the blood vessels in the brain, especially in children. Narrowing and blockage ...

-

A model patient: Alexia’s triumph over moyamoya disease

If you’re lucky enough to get time on Alexia’s packed schedule, you’re in the company of a ...