A better treatment for endometriosis could lie in migraine medications

Endometriosis is a common, mysterious, often painful condition in which tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus, forming lesions in locations such as the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and pelvis. These lesions can cause severe pain during periods, heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic or abdominal pain, and sometimes painful bowel movements and urination.

Existing treatments for endometriosis have changed little in 30 years and are often ineffective or have side effects. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and painkillers don’t always work, and many patients don’t want to use hormones since they interfere with getting pregnant. Surgery can remove some of the lesions, but they often return.

Recent research led by Boston Children’s Hospital researchers Michael Rogers, PhD, and Victor Fattori, PhD, uncovers some surprising new endometriosis biology involving crosstalk between the nervous system and the immune system. It also points to a new, non-hormonal class of drugs that the FDA has already approved to treat migraine. Rogers is now exploring partnerships with pharmaceutical companies to launch a clinical trial.

From cancer to endometriosis

A decade ago, Rogers was pursuing cancer-related projects in the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s when a friend with endometriosis urged, “Mike, you’ve got to start studying this.”

It wasn’t such a leap as it might seem. Vascular biology largely focuses on blood vessel growth, or angiogenesis. Endometriosis — like cancer — is dependent on angiogenesis.

At the time, the entire federal budget for endometriosis was less than $10 million. “As a cancer biologist, I assumed there would be a similar research community working on endometriosis,” says Rogers. “That turned out not to be true.”

About three years in, Fattori joined Rogers’ lab and led the development of a mouse model that mimics the lesion growth and severe pain of endometriosis. The team set about testing dozens of drug candidates in the model, guided by clinical partners Amy DiVasta, MD, chief of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine and Marc Laufer, MD, chief of the Division of Gynecology.

“We prioritized options that would be acceptable, particularly to adolescents and young adults,” says DiVasta. “Mike was thoughtful in looking at options that were already commercially available, that could be available very quickly if they were proven to be effective. Our patients and families are desperately looking for an alternative to hormonal treatments.”

Focusing on neuro-immune communication

Fattori was then a visiting graduate student shared by the Rogers lab and the lab of Clifford Woolf, MB BCh, PhD, a world expert on neural pain pathways, including communication between pain-sensing neurons (nociceptors) and immune cells. Fattori brought valuable expertise and insights to the project through his work on neuroimmune communication and more than 15 years of experience with different models of pain.

“We started thinking about how the nervous system can talk to immune cells and help shape immune cell function and inflammation in endometriosis,” Rogers says.

Blocking a factor from nociceptors eases pain, shrinks lesions

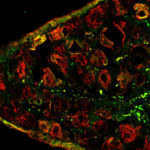

In work recently published in Science Translational Medicine, Rogers and Fattori (now an instructor in the Vascular Biology Program in the Rogers lab) focused on one factor released by nociceptors, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). They showed that CGRP communicates with macrophages (immune cells that digest debris) and leads to increased endometrial cell growth.

Studying tissue samples from eight patients with endometriosis, as well as their mouse model, the team found that endometriosis lesions contain nerve fibers with both CGRP and its receptor, RAMP1.

Further work suggested that CGRP reprograms macrophages and makes them less able to clear debris, leading to inflammation that likely promotes endometriosis pain. Moreover, the altered macrophages were found to secrete molecules that help endometriosis lesions grow.

As it happens, the FDA had already approved multiple CGRP inhibitors to treat migraine, which also has a neuro-immune component. Research led by DiVasta had found that migraines are especially common in adolescents with endometriosis. Rogers and Fattori gave four different CGRP/RAMP1 signaling inhibitors (two antibodies against CGRP and two small molecules that block the RAMP1 receptor) to mice with endometriosis lesions — and saw reduced pain behavior and reduced lesion size with all four.

DiVasta and Laufer have already been testing other drugs in patients, such as cabergoline, an angiogenesis inhibitor, based on mouse data from the Rogers lab. “Our relationship with Mike has gone both ways,” says DiVasta. “What he’s seen in the mouse models has informed the development of clinical trials.”

Visit the Rogers Laboratory and stay up to date on Boston Children’s research by subscribing to our monthly newsletter.

Related Posts :

-

Mouse model could lead to new treatments for endometriosis pain

There are few effective long-term treatments for endometriosis; even fewer options for relieving the often severe pain associated with the ...

-

Drug repurposing and DNA mining: The hunt for new endometriosis treatments

Endometriosis is a common gynecological condition that may affect more than 1 in 10 reproductive-age women. Yet, there’s very little research ...

-

Explaining endometriosis: What parents and teens should know

People with uteruses know that menstruation can bring cramps, general discomfort, mood swings, and other symptoms each month. But, just ...

-

Out of balance: How hormones can affect your child’s period

If your tween or teen is experiencing irregular periods, they aren’t alone. In the first two years after getting ...