Vertebral body tethering: Is it an option for my child?

For years, teens and tweens with idiopathic scoliosis had three treatment options: monitoring, bracing, or spinal fusion surgery. A new option emerged in 2019 when the Food and Drug Administration approved a treatment called vertebral body tethering (VBT). Compared to spinal fusion surgery, VBT offers quicker recovery times and the potential for greater spine mobility after surgery.

However, VBT also comes with a host of questions. While early studies have deemed vertebral body tethering safe, physicians have very little information about the procedure’s long-term risks or how stable their patients’ spines will be five, 10, or 20 years from now.

Here, Dr. Daniel Hedequist, chief of Boston Children’s Spine Division, talks about vertebral body tethering and what patients and families should consider when deciding if it’s a good option for them.

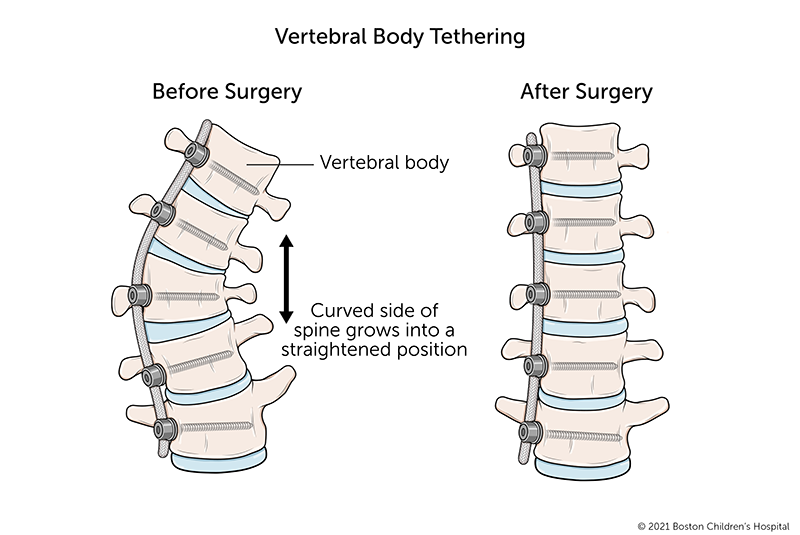

How does vertebral body tethering work?

Vertebral body tethering restricts the growth on one side of a scoliosis curve so the spine will grow straighter. We do this by attaching a flexible cord, known as a tether, to the spine on the outside of the curve. As the child grows, the tension of the tether allows the other side of the spine to lengthen out and catch up with the tethered side.

Who might benefit from vertebral body tethering?

Patients need to have enough growing left that their spine can grow straighter after the procedure. The location of the curve is also important. VBT may maintain some mobility in the affected area of the spine. This matters most if the curve is in a highly mobile section of the spine, such as the lumbar (lower) spine. The thoracic (mid) spine is less mobile, so lost mobility there will have less of an impact on a patient’s future activities.

Could vertebral body tethering work for an older teen?

In most cases, probably not. This procedure works by changing how the spine grows and is most effective during the adolescent growth spurt. For girls, this typically takes place between the ages of 10 and 14. On average, boys tend to gain the most height between the ages of 12 and 15. Once a young teen has finished growing, it’s no longer possible to affect the growth of their spine.

What remains unknown about vertebral body tethering?

Things to think about when considering VBT

- Is my child at a stage of growth where VBT could correct their scoliosis?

- Is the curve in a mobile section of the spine?

- Is the curve within the range of 30 to 60 degrees?

- How would my child be affected if the section of their spine with scoliosis were immobile?

- How comfortable are we with the uncertainties around this procedure?

Vertebral body tethering may maintain spinal mobility, but that hasn’t been proven and we don’t know how much mobility the patient will maintain over time.

We also don’t know the potential long-term effects of attaching the tethering device to the spine. Because the spine has more mobility, there will likely be some friction where the tether attaches to the screws. Potentially this could generate debris in the chest or abdominal cavity, which could, in theory, create scar tissue. We have seen this with other moveable devices placed in the body, such as with total joint replacements that later required revision surgeries.

Do you have any advice for families trying to decide between vertebral body tethering and spinal fusion?

I think it’s helpful to look at the surgical options side by side: vertebral body tethering and spinal fusion surgery. Then think about your child’s stage of growth, the activities that are important to them, and the level of uncertainty you feel comfortable with.

Vertebral tethering could be a good option for an athlete who’s on the cusp of their pre-adolescent growth spurt who participates in activities that require spinal mobility.

Spinal fusion surgery may be a better option for patients who do not place as much value on spine mobility or feel uncomfortable undergoing a new procedure. It’s definitely a better option for patients who have finished growing or have severe scoliosis (a curve of 60 degrees or more).

What are the pros and cons of vertebral body tethering compared to spinal fusion surgery?

Pro: Shorter recovery time

Vertebral body tethering is less invasive than spinal fusion surgery, and the recovery time is shorter. Typically, patients can return to school and most other activities three to four weeks after the procedure.

Most kids can return to school within that same period after spinal fusion surgery. But it generally takes three to six months before they can play sports and six months to a year for the affected vertebrae in their spine to fuse.

Pro: Potential for greater mobility

Theoretically, patients have more spinal mobility after VBT, though we don’t know yet how much mobility they can expect. By contrast, we know for sure that after spinal fusion surgery, the fused section of spine will no longer bend.

Con: High rate of follow-up surgeries

In studies of patients who have had VBT so far, between 15 to 20 percent have had unplanned follow-up surgeries. For some, a broken tether had to be replaced or they had failure of the screw(s). For others, one of the screws used to attach the tether to the spine came loose. In a small number of patients, VBT failed to prevent scoliosis from progressing, and they had to have spinal fusion surgery.

By comparison, only about 3 percent of patients who have spinal fusion surgery for similar curves need follow-up surgery.

Con: Greater uncertainty

Because VBT is a new procedure, there are many things we don’t yet know about it. We won’t know them until many more patients have had the procedure and their physicians follow them for a number of years and report on their outcomes.

Learn more about the Spine Division.

Related Posts :

-

A new treatment option for Jeanne’s infantile scoliosis

If it hadn’t been for the pandemic, Jeanne McDaniel’s treatment for infantile scoliosis would have started when she ...

-

A modified brace and a new treatment option for infantile scoliosis

While bracing is a common treatment for adolescents with moderate idiopathic scoliosis, infantile scoliosis is typically treated with casting. But ...

-

Scoliosis bracing: How to support your child

Q&A with M. Timothy Hresko, MD and Deborah Cranford, RN Most patients with idiopathic scoliosis will never need ...

-

Generations of excellence in surgical care: Dr. Emans and Dr. Hogue

Some surgeons follow their patients for years, even decades. This is true of Dr. John Emans, who has treated patients ...