Two decades of innovation in pulmonary vein stenosis

Over the past 20 years, the Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Program at Boston Children’s Hospital has been crafting an innovative strategy in its approach to pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) based on a new way of thinking about this rare and unusual disease.

“The breakthrough came in realizing that PVS is not like other types of congenital heart disease,” says cardiologist Kathy Jenkins, MD, MPH. “Other types of CHD don’t grow back. This disease does.”

For Jenkins, the breakthrough began nearly 20 years ago, when a premature baby from Albany arrived at Boston Children’s for PVS treatment. The baby underwent surgical repair by Pedro del Nido, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Boston Children’s, recovered and was sent home. Four weeks later, she was back at the hospital in critical condition. Del Nido came out of the operating room shaking his head, knowing she wasn’t going to make it.

Jenkins was the baby’s cardiologist. She asked del Nido why he was so sure the baby would die.

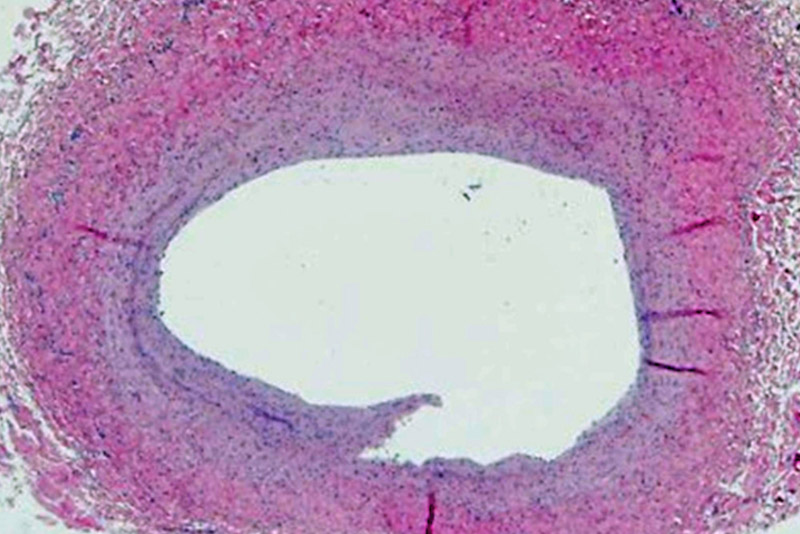

“He told me there was white material in her pulmonary veins that he had cleaned out during the first surgery, and now, just four weeks later, it was all back,” says Jenkins.

Jenkins went home wondering about the white material. She called the clinical chief of oncology and asked about their approach to disease that recurs. He put her in touch with neuro-oncologist Mark Kieran, MD, PhD.

“Mark suggested it would be easier to form a treatment strategy if we could get some idea from pathology about what the white material was,” says Jenkins.

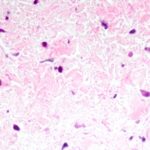

She headed to pathology and found Puay Tan, MD, who was able to find specimens from kids who had died of PVS in the heart autopsy registry. She discovered a very consistent cellular pattern in all the patients.

“An idea emerged that we needed to understand more about that cell and then find a way to suppress its growth,” says Jenkins.

Jenkins recruited a fellow, Irene Sadr, MD, to help. Based on pathology, they discovered the white material was likely a myofibroblastic type cell. They brought these results to Kieran, who said there was a cancer cell that was similar, called a desmoid tumor.

“They already had a drug regimen for babies with desmoid tumors, so that became the rationale for a clinical protocol,” says Jenkins. “We learned the concept was right, but the drugs [vinblastine and methotrexate] had high toxicity in our population, so some doctors and parents stopped the treatment as soon as the patient had side effects. This made it difficult to interpret the results.”

Undaunted, Jenkins and her team continued working with pathology. Tucker Collins, MD, PhD, who was the chief of Pathology at that time, became interested and discovered the cells had tyrosine kinese receptors. With help from Kieran, they found two drugs (imatinib mesylate and bevacizumab) that had been developed specifically to block those receptors and were already being used in pediatric oncology; in 2009, they moved forward with a single-arm trial. The team recently published their results in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“It started as a research program but very quickly evolved into a clinical program, as PVS families started hearing about it and wanted another treatment option,” says Jenkins. “The approach is working without undue toxicity to the young patients, and even though the study stopped enrolling the program continues to treat patients and get national referrals.”

As the number of patients expanded, Jenkins recruited Christina Ireland, RN, MS, FNP, to the program to help manage patients. Ireland, who won a national Daisy Award for her role with PVS patients, says that aggressive follow-up has been a big part of the program’s success.

“I’ve been a nurse here in cardiology for more than 20 years and I remember those original PVS patients were often coming back to the hospital in crisis,” says Ireland. “Since I started in this role six years ago, we haven’t seen that. I think part of our success comes from being available for families to triage vague symptoms like feeding intolerance or fast breathing that require a visit with a cardiologist. We know that with this disease you can’t rely on what the kids look like, you need to do more frequent tests.”

Jenkins agrees that aggressive surveillance of the condition is part of the reason they are no longer seeing kids in crisis. She also credits her colleagues in interventional catheterization and surgery with rethinking their approach to PVS treatment.

“We’re the first to say it may not just be the drugs,” says Jenkins. “All of the advancements we’re making are critical.”

In 2015, interventional cardiologist Ryan Callahan, MD, joined the team, and has focused on modifying his approach to PVS in the catheterization lab, learning how to achieve better, more effective dilations with traditional equipment.

“Our efforts are focused on how to better understand the disease inside the cath lab through interpretation of angiography and with intravascular ultrasound,” says Callahan. “We’re very cognizant of how the balloons are behaving inside the veins and of which balloon to choose next to get the most effective dilation.”

He says that stents have also evolved over time.

“We’ve learned that larger stents tend to work better in terms of keeping the vessel open and avoiding significant in-stent restenosis,” says Callahan. “If we have to place a small stent, we’re using drug-eluting stents, which are typically reserved for the adult world. These approaches have allowed us to keep vessels open that would otherwise be lost.”

According to Jenkins, expertise in the cath lab has also yielded more information about the progression of the disease and a better understanding of its nuances.

“We get referrals all the time from other centers who simply don’t feel comfortable catheterizing these patients,” says Jenkins. “It’s not that other clinicians don’t have the skill, but they simply don’t see the number of cases to develop the level of expertise our department has.”

In surgery, Christopher Baird, MD, is leading the way in reframing the department’s thinking around surgical treatment of PVS.

“With PVS, it’s not just one vein, but up to five veins, each with its own unique surrounding anatomy,” says Callahan. “Dr. Baird’s approach is to see what intervention will improve the anatomy and geometry of each individual vein. We’re also starting to focus on laminar flow in the vein as a priority.”

Baird has also questioned the traditional suture-less repair of the veins. “He’s putting sutures in these veins and they are staying open,” says Callahan.

However, as much as the team has had success, they acknowledge there is still more to learn.

“We’re finding new ways to treat a disease that was killing babies rapidly,” says Jenkins. “We’re not saying that every baby lives, but we have a strategy. It’s a rare disease and reframing our thinking about PVS is part of an evolution.”

Learn more about the Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Program.

Related Posts :

-

The ‘Trach Chapter’: Isabella’s journey with bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Isabella’s life has been anything but ordinary. Born at just 27 weeks gestation and weighing only 1 pound, 4 ounces, Isabella has ...

-

From Pakistan to Boston: Faiz finally found help for his complex heart condition

Don’t let his shy smile fool you. In his hometown of Lahore, Pakistan, 6-year-old Muhammad Butt is known by ...

-

The brightest rainbow follows the darkest storm: Our PVS journey

Caroline is our rainbow baby, born after the loss of another child, the light and color arising after a storm ...

-

Trial shows chemotherapy is helping kids live with pulmonary vein stenosis

Pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is a rare disease in which abnormal cells build up inside the veins responsible for ...