The softer the nanoparticle, the better the drug delivery to tumors

For the first time, scientists have shown that the elasticity of nanoparticles can affect how cells take them up in ways that can significantly improve drug delivery to tumors.

A team of Boston Children’s Hospital researchers led by Marsha A. Moses, PhD, who directs the Vascular Biology Program, created a novel nanolipogel-based drug delivery system that allowed the team to investigate the exclusive role of nanoparticle elasticity on the mechanisms of cell entry.

Their findings — that softer nanolipogels more efficiently enter cells using a different internalization pathway than their stiffer counterparts — were recently published in Nature Communications.

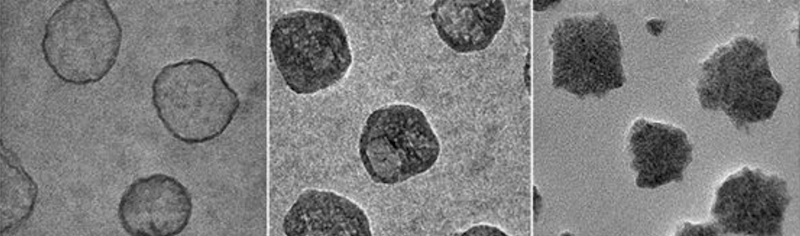

The custom-tuned nanolipogels engineered by Moses and her collaborators comprise a core and a shell. The shell consists of a double layer of lipids which surround a core of alginate hydrogel, an FDA-approved, safe biomaterial derived from polysaccharides (chains of sugar molecules) found in seaweed. Alginate hydrogels are mostly made up of water and their elastic properties can be modulated by tuning the extent of their ionic crosslinking, which is the bonding together of molecules.

Importantly, the crosslinking of the nanolipogel’s core can be achieved without affecting the surface properties of the shell, allowing Moses and the team to investigate elasticity’s role independently of other factors.

Getting cancer therapies where they are needed most

Testing different versions of the nanolipogels in vitro in an aggressive type of human breast cancer cells, the team observed that the softest iterations were taken up by tumor cells nearly 80 percent more than the stiffest nanolipogels.

What’s more, in contrast to the well-established theory that nanoparticles enter cells predominantly through receptor-mediated endocytosis — which is when cells engulf molecules at certain sites on the cellular membrane containing receptors specific to what’s being taken in — the team found that the softest nanolipogels were able to fuse with the cell membrane and move directly into the cell where they can deliver their drug payload.

Next, in a mouse model of triple-negative, highly malignant breast tumors — a type of cancer which currently lacks effective treatment options in humans — the team discovered that the more direct, fusion-dominated cell entry pathway allowed the soft nanolipogels to accumulate inside tumor cells at more than two-fold greater amounts than stiff nanolipogels.

Read a highlight about the findings in Nature Nanotechnology.

Taken together, their findings demonstrate the importance of leveraging biomechanical factors to regulate interactions between nanomaterials and biological systems, with the ultimate goal of creating successful drug delivery strategies.

Moses, senior author on the study, is also the Julia Dyckman Andrus Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School (HMS). The paper’s lead author is Peng Guo, PhD, a researcher in the Moses Lab and an Instructor in Surgery at HMS. The study was conducted in collaboration with Debra Auguste, PhD, and her team in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Northeastern University. Additional authors on the paper are Daxing Liu, Kriti Subramanyam, Biran Wang, Jiang Yang and Jing Huang.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants 1DP2CA174495 and R01CA185530) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Related Posts :

-

A new druggable cancer target: RNA-binding proteins on the cell surface

In 2021, research led by Ryan Flynn, MD, PhD, and his mentor, Nobel laureate Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, opened a new chapter ...

-

Forecasting the future for childhood cancer survivors

Children are much more likely to survive cancer today than 50 years ago. Unfortunately, as adults, many of them develop cardiovascular ...

-

Pediatric high-grade gliomas: Research reveals effective targeting with avapritinib

Pediatric high-grade gliomas, particularly H3K27M diffuse midline gliomas (DMG), are aggressive malignant brain tumors with a poor prognosis. ...

-

A better treatment for endometriosis could lie in migraine medications

Endometriosis is a common, mysterious, often painful condition in which tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus, ...