The exciting life of Jack, the first successful fetal cardiac intervention patient

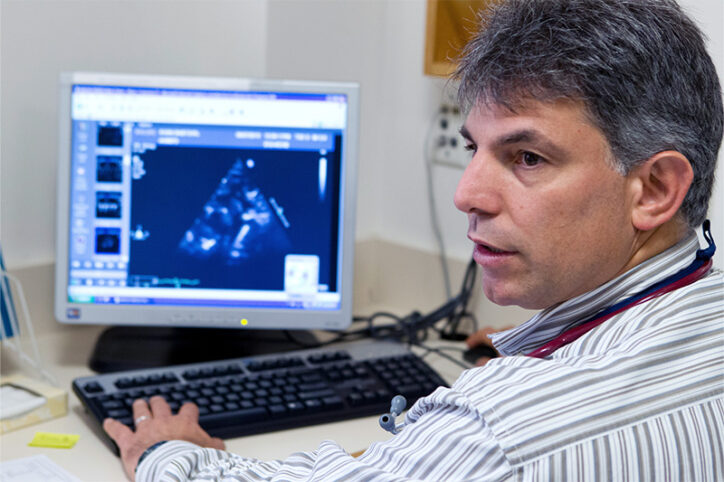

Jack Miller sometimes reaches out to his cardiologist, Dr. Wayne Tworetzky, with updates on his life.

Recently, their conversations centered around Jack pushing himself while training to be a police officer. The physical endurance Jack needed for training was another example of how the fetal cardiac intervention that Dr. Tworetzky and the specialists of the Fetal Cardiology Program performed on Jack 24 years ago was a success.

It was, in fact, the first successful fetal cardiac intervention — the first time anywhere that a fetus underwent a procedure that prevented an evolving severe heart defect from creating a single-ventricle circulation and instead allowed the child to be born with a normal two-ventricle circulation.

But while Jack appreciates his place in history, the procedure has another meaning for him: Before he was even born, it gave him a chance to become who he is now, a police officer and athlete. “I owe my life to Dr. Tworetzky and Boston Children’s,” he says. “They figured out a way to make sure I can live my life.”

Expertise and technology created a needed treatment

Years before Jack’s procedure, fetal cardiac specialists recognized that many fetuses diagnosed with aortic valve stenosis had developed, by birth, a severe congenital heart defect known as hypoplastic left-heart syndrome (HLHS). They wanted to treat the valve in utero, before HLHS could progress, but the proper technology wasn’t yet available, says Dr. Tworetzky, director of the Fetal Cardiology Program.

By the time Jack’s mother, Jennifer, had an ultrasound in early 2001 that revealed Jack’s aortic valve stenosis could lead to HLHS, the technology had finally met the moment. Dr. Tworetzky and a team of specialists were ready to make the fetal cardiac intervention a viable treatment option.

“It took people who were out of their comfort zones working together,” Dr. Tworetzky recalls. “The obstetricians had never done cardiac procedures, and the cardiology team had never done obstetric procedures. We needed each other to make it work.”

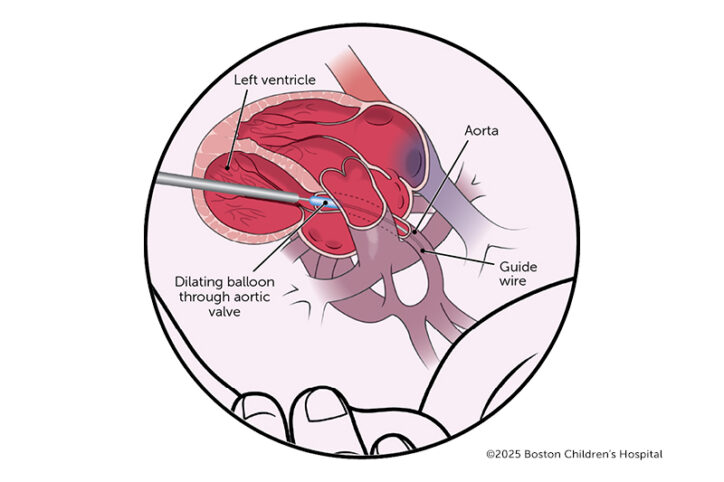

For Jack’s procedure and the 260 procedures the Fetal Cardiology Program has performed since, each specialist has had a clear role: Anesthesiologists administer anesthesia to the fetus while giving an epidural or anesthesia to the mother. Maternal fetal medicine specialists move the fetus into position and insert a needle through the uterus and into the fetal chest and heart — all under the guidance of ultrasound. Interventional cardiologists then perform a balloon dilation of the aortic valve, a process that’s performed through the needle.

“Everyone on the team and in the operating room has a different skill set, but it’s a lot like skydiving,” Tworetzky says. “Everyone jumps out of the plane, forms a circle, links hands, and works together to make sure everyone lands safely.”

A normal life that happened to make the record books

The intervention opened Jack’s narrowed aortic valve, allowing his left ventricle to pump more effectively and develop normally. Growing up, he naturally embraced his good health without realizing he almost didn’t have it. “I didn’t know I was in the 2003 Guinness Book of World Records until my fifth-grade teacher noticed my name and asked me about the procedure,” he says.

When Jack went home, his father, Henry, and Jennifer explained his heart condition in detail. To this day, the 23-year-old hasn’t had any physical setbacks, and since the fifth grade he hasn’t needed any more cardiac catheterizations on his aortic valve. He’s had a normal life, even though he does things many people wouldn’t normally do. Jack has boxed, surfed, skydived, and skateboarded on boards he made himself. He also played baseball, a sport he pursued into college until he tore a rotator cuff.

Jack’s love for testing boundaries stems in part from him not embracing the typical identity of a heart patient; he doesn’t think of himself as one. “I push my limits. It’s all about being active. And if I can’t push myself by a foot, I’ll at least try to move ahead six inches.”

A new career starts but Boston Children’s is still home

Few people know Jack has a heart condition, let alone received treatment that made history. He only recently started sharing his story. On his second day at a municipal police academy, Jack told his fellow cadets he was the first successful fetal cardiac intervention patient. “They didn’t see that icebreaker coming.”

At the academy, Jack had to exert himself more than ever before. To be safe, during training he had two checkups with Dr. Tworetzky, instead of his usual annual visit. He graduated and is now a police officer in Ipswich, Massachusetts.

Jack looks forward to sharing the details of this exciting new chapter in his life at his next appointment with Dr. Tworetzky. He has no intention of going anywhere other than Boston Children’s for heart care. “I trust them and am forever in debt to everyone there.”

Learn more about the Fetal Cardiology Program.

Related Posts :

-

The people and advancements behind 75 years of Boston Children's Cardiology

Boston Children’s Department of Cardiology has more than 100 pediatric and adult cardiologists, over 40 clinical fellows learning the ...

-

Finding a way to help newborns who can't immediately have heart treatment

Newborns with complex congenital heart defects (CHD) and pulmonary overcirculation often need treatment as soon as possible. Unfortunately, ...

-

Unique data revealed just when Mickey's heart doctors could operate

When Mikolaj “Mickey” Karski’s family traveled from Poland to Boston to get him heart care, they weren’t thinking ...

-

Past patient outcomes could help single-ventricle surgery decisions

When considering whether a child who has a single-ventricle heart defect would benefit more from biventricular repair&...