Talking with your child about loss and death

The death toll from COVID-19 has recently surpassed more than 400,000 in the United States and continues to climb. This means that thousands of children have lost someone close to them — a grandparent, an aunt or uncle, a family friend, or even a parent. Some children have lost more than one loved one.

Talking about loss and death with children is never easy. For guidance, we turned to Erica Lee, a psychologist in the Department of Psychiatry at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Be honest

If you are faced with the serious illness of a loved one, Lee says it’s best to be as honest with kids as you can. “It can be hard to share the truth about death or loss. However, children respond better to bad news when someone they love delivers it. This builds trust and safety and reassures them they can rely on you to help make sense of the situation.”

Lee says if a loved one is very sick and you don’t tell your child, they might feel betrayed or scared if they learn about it later, or if that person dies. “Every family and culture approaches death in their own way, but try to avoid withholding too much information,” says Lee. “It’s okay if you don’t have all the answers. Share as much as you can in a way that’s appropriate for your child’s age and what they can handle and encourage them to ask questions.”

Plan your talk, but don’t wait too long

While grief experts recommend telling children about a loved one’s death sooner rather than later, Lee says you may want to take a little time to process the loss yourself. Then decide who is the best person to relay the news to your child, whether it’s one parent, both parents, or another close caregiver. “Offer younger children something soothing to hold, such as a favorite blanket or stuffed animal,” says Lee. “As you talk, try to be fully present and speak as clearly and empathically as you can.”

If you have older children who are away at school, Lee suggests telling them as soon as possible. “A delay might mean that they hear it from someone else first, especially in this age of social media,” she says.

Help kids understand

Lee says that what you share will depend on your child’s age. Children under age 5 may need help understanding what death means. “They may see death portrayed in TV shows or movies, but often don’t understand it’s permanent and irreversible,” says Lee. “You want to be brief and use clear and simple language. Avoid using euphemisms that could confuse kids, such as saying that your loved one ‘went to sleep’ or ‘has gone away.’”

Instead, she suggests explaining that death means the individual is no longer with us and cannot come back. “Use a concrete example that your child can understand, like how a dead bug doesn’t fly or eat or grow anymore.”

School-age kids might have lots of feelings and thoughts about death, and may worry that other people may also die. “You can reassure them that you are safe and list some of the ways you take care of yourself,” says Lee.

She says that teens may start to ask questions about the meaning of life and death. “You can engage with them on this level without having all the answers. Be open to these conversations, and to exploring these ideas further together,” says Lee.

Give them space to grieve

Grief can take many forms, so be prepared for a wide range of reactions. “Children may express sadness, anger, worry, frustration, or confusion when someone close to them dies,” Lee says. “Some may seem sad and want to talk about it; others may show how they feel through play or art. Older kids may want more alone time, while younger kids may be more clingy than normal.”

Kids might also have trouble concentrating, especially in school, or may complain of physical symptoms, such as headaches or stomachaches. “You may want to tell your child’s teachers there’s been a loss so they can give them some time to grieve,” says Lee.

Find a way to say goodbye

These days, most people are holding memorials and services virtually. But you can also help your child find more personal ways to remember your loved one. Lee suggests gathering physical mementoes of that person, putting together a photo album, planting a flower or tree in their memory, or visiting a special place that reminds you of them. “You could also listen to music they loved, donate to a cause that was meaningful to them, or have a meal that reminds you of time you spent together,” says Lee.

Know when to seek support

“Grief is a natural part of life, and it’s healthy and important to grieve,” says Lee. “Most kids will bounce back, but it’s also common for them to feel triggered by reminders of the loved one and their loss, such as milestones, holidays, birthdays, or seeing a special place.”

However, if your child seems to be experiencing deep grief that lasts longer than six months, they may need extra behavioral health support. Lee says the National Alliance for Grieving Children is also a great resource for support.

“If a child doesn’t go back to their usual activities, or if they start talking about wanting to die or going to be with that person, those are also signs that you should reach out to their primary care physician or a behavioral health specialist for more help,” says Lee.

Learn more about Boston Children’s response to COVID-19.

Related Posts :

-

Help your child manage anxiety about school violence

With news of school shootings and other violence often reaching children, parents sometimes grapple with how to help their child ...

-

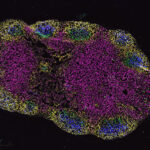

Model enables study of age-specific responses to COVID mRNA vaccines in a dish

mRNA vaccines clearly saved lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, but several studies suggest that older people had a somewhat reduced ...

-

New insight into the effects of PPIs in children

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently prescribed to suppress stomach acid in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Prescribing rates of ...

-

Creating the next generation of mRNA vaccines

During the COVID-19 pandemic, mRNA vaccines came to the rescue, developed in record time and saving lives worldwide. Researchers in ...