Pearson syndrome and the story of William’s cells

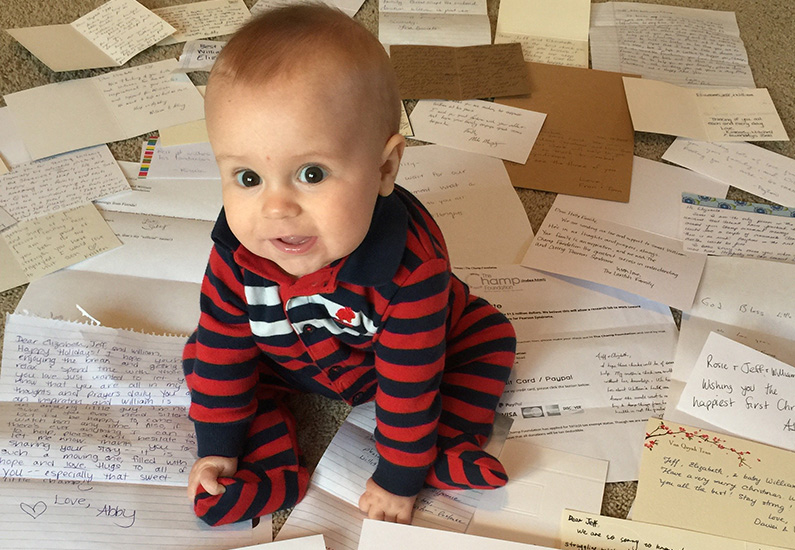

William will often ask to hear the “story about his cells.” His mom and dad, Elizabeth and Jeff Reynolds, are always honest. Yet, it is difficult for the 4-year-old to understand words like mitochondrial disease or myelodysplastic syndrome. He also can’t comprehend his parents’ pursuit of a novel treatment for Pearson syndrome, which led them to Israel and to the unexpected discovery in William’s bone marrow.

So instead, they tell William he had “naughty cells.” They explain how they saved cells from his little brother, Teddy, in a big freezer, and now those cells are helping William feel better and stay healthy.

Pearson syndrome

William is one of fewer than 100 children worldwide known to have Pearson syndrome, a rare, multi-system, mitochondrial disease that has no cure and is often fatal. Its most common manifestations are sideroblastic anemia and pancreatic insufficiency, but it can also impair the liver, kidneys, heart, eyes, ears, and brain.

Pearson syndrome is caused by a deletion in the mitochondrial DNA, which can make it difficult for the cells in a child’s body to make energy. It is challenging to diagnose, because it overlaps clinically with other syndromes, and few pediatric hematologists are even aware of its existence.

“The genetics are tricky,” says Dr. Suneet Agarwal, co-program leader for the Stem Cell Transplant Center at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, who has been studying Pearson syndrome for the last 12 years. In a 2014 paper, Dr. Agarwal and fellow researchers described how Pearson syndrome is frequently overlooked and often masquerades as Diamond-Blackfan anemia. “You have to be looking for this specific problem in the mitochondrial genome, which is separate from the nuclear genome,” says Agarwal. “And it’s such a rare disease that doctors often don’t go looking for that.”

Birth of the Champ Foundation

Doctors at Duke University, where William was born, initially suspected he had a rare childhood anemia, but following consultations with Boston Children’s Hospital Pathologist-in-Chief Dr. Mark Fleming and further genetic testing, it was determined he had a far more serious condition — Pearson syndrome.

“This was absolutely the worst-case scenario,” says his mom, Elizabeth. “William seemed healthy and normal. It was hard to believe.”

Determined to find a treatment for their son, the Reynolds began seeking the advice and guidance of specialists across the country. They traveled to Boston to meet with Dr. Agarwal, one of the few physicians to have ever seen a child with the disease.

“We learned he had been studying Pearson syndrome, but as often is the case with a rare disease, it is difficult to get funding,” Elizabeth says. “That was unacceptable to us — to have high-quality researchers unable to study the disease because of financial limitations.”

In November 2015, two months following William’s diagnosis, Jeff and Elizabeth established The Champ Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to funding Pearson syndrome research. The first grant was awarded to Dr. Agarwal and his lab at Boston Children’s.

Since then, Dr. Agarwal has not only been expanding his research, but also serving as a Champ Foundation scientific advisory board member. In February 2018, he helped the Reynolds organize the first-ever Pearson syndrome conference, which brought together physician-scientists from around the world to Boston Children’s, and helped set the stage for further collaboration.

While the Reynolds forged ahead in their efforts to fuel research, William remained stable during the next two years of life. His low blood counts improved, as sometimes happens in Pearson syndrome, and he remained free of other symptoms.

In July 2019, he was set to participate in a mitochondrial augmentation therapy clinical trial at the Sheba Medical Hospital in Israel. One of the early tests required was a bone marrow biopsy, which resulted in a secondary diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) — a “pre-leukemia” that affects the production of healthy blood cells in the bone marrow — precluding him from participating in the clinical trial.

“The day we got this diagnosis in Israel, we were on the phone with Dr. Agarwal,” says Elizabeth. “We came back to North Carolina and pretty much immediately turned around and went to Boston.”

Replacing the ‘naughty cells’

When Teddy, Williams’s baby brother, was born, the Reynolds had the foresight to save the umbilical cord blood. Rich with stem cells that can be transplanted into a sick patient, the cord blood helps grow new cells and replace diseased ones.

“We were aware that other kids with Pearson syndrome sometimes have secondary diagnoses, like MDS, and we knew Teddy and William were a genetic match.”

This past fall, William received his cord blood stem cell transplant at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s. Recently, he reached the 100-day post-transplant mark. “A day to celebrate,” says his mom. “The transplant was a success, and we are incredibly grateful to the transplant team at Boston Children’s and for Dr. Agarwal.”

Although William’s stem cell transplant corrects the hematologic aspects of his condition, it cannot correct the problems occurring in other parts of the body. “This is a systemic disease,” says Dr. Agarwal. “When the blood gets fixed, it takes a lot of concerns off the table, but we still need to figure out a way to actually fix the entire body.”

Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

Earlier this month, The Champ Foundation was awarded a $450,000 grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) to develop a Pearson syndrome research network. The grant is part of CZI’s Rare As One Project, aimed at supporting and lifting up the work patient communities are doing to accelerate research and drive progress in the fight against rare diseases.

With Dr. Agarwal at the research helm, the two-year grant will steer the field to investigate high-potential pathways and accelerate Pearson syndrome research.

“We’re racing to discover treatments for the next wave of problems,” says Dr. Agarwal. “For parents like Elizabeth and Jeff, there’s a heightened level of precaution and a constant worry that something else is coming. My hope is we can stop it before it does.”

Learn more about Pearson syndrome.

Related Posts :

-

BRD7 research points to alternative insulin signaling pathway

Bromodomain-containing protein 7 (BRD7) was initially identified as a tumor suppressor, but further research has shown it has a broader role ...

-

In the genetics of congenital heart disease, noncoding DNA fills in some blanks

Researchers have been chipping away at the genetic causes of congenital heart disease (CHD) for a couple of decades. About 45 ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity and ...

-

Microvillus inclusion disease: From organoids to new treatments

Microvillus inclusion disease (MVID) is a rare type of congenital enteropathy in infants that causes devastating diarrhea and an inability ...