If another pandemic hits, our online ‘footprints’ may help the experts

When the new coronavirus hit early last year, little was known about it. As people started coming to the emergency room, doctors scrambled to understand COVID-19 and its trajectory of symptoms. Testing was limited, and only over a period of months did the full fury of the new virus make itself known. Community after community became infected without realizing a dangerous virus was circulating.

Two studies from the Boston Children’s Hospital Computational Health Informatics Program (CHIP) suggest that studying people’s Internet searches and other digital activity could help the public health community better prepare when future pandemics hit.

From fever to shortness of breath

Could the effects of a new, unknown illness be anticipated in advance? Data scientist Ben Reis and Harvard University undergraduate Tina Lu tackled this question by looking back at the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. They analyzed publicly available Google Trends data on millions of online searches in 32 affected countries from January to April 2020.

“Our goal was to reveal the clinical course of an illness over time, and to predict the expected course of symptoms,” says Reis, who directs CHIP’s Predictive Medicine Group.

Indeed, as Reis and Lu reported recently in Nature Digital Medicine, Internet searches closely matched the timing of COVID-19 symptoms as eventually reported in the medical literature.

Predicting disease symptoms

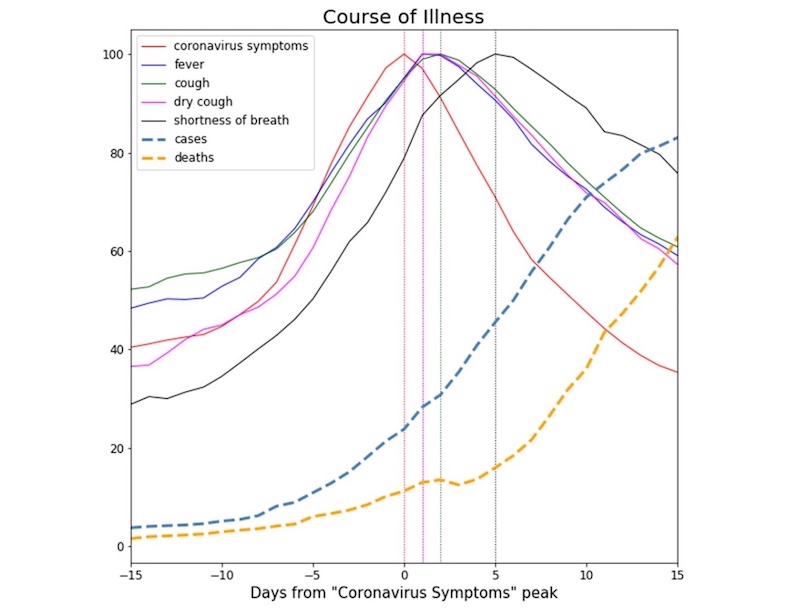

Searches on “coronavirus symptoms” and “coronavirus test” were first to peak in many countries. Searches for “fever,” “dry cough,” “sore throat,” and “chills” preceded searches for “shortness of breath” by an average of 5.2 days — similar to formal reports that came out months later.

Overall, spikes in COVID-19 symptom-related searches preceded spikes in confirmed cases by an average of 18.5 days, and preceded deaths by an average of 22 days. The findings were generally consistent across the 32 countries.

“Hopefully, our findings can be replicated for future emerging pandemics, empowering health officials to make more educated decisions earlier,” says Lu.

Internet access levels differ across countries and communities, and searches on terms like “fever” aren’t always COVID-19-related. But the trends Reis and Lu saw stood out from this statistical background noise.

“Public health officials could use Internet searches to complement other surveillance methods when there’s a new pandemic and not much data about the disease course,” says Reis. “Search data can also capture people who are sick but aren’t going to the hospital. Once health authorities know what to expect, they can better plan the allocation of hospital resources such as beds and ventilators.”

Capturing outbreaks in near real time

In a separate study published today in Science Advances, data scientist Mauricio Santillana reports that people’s digital footprints, drawn from a variety of sources, can accurately forecast where an outbreak will surge next.

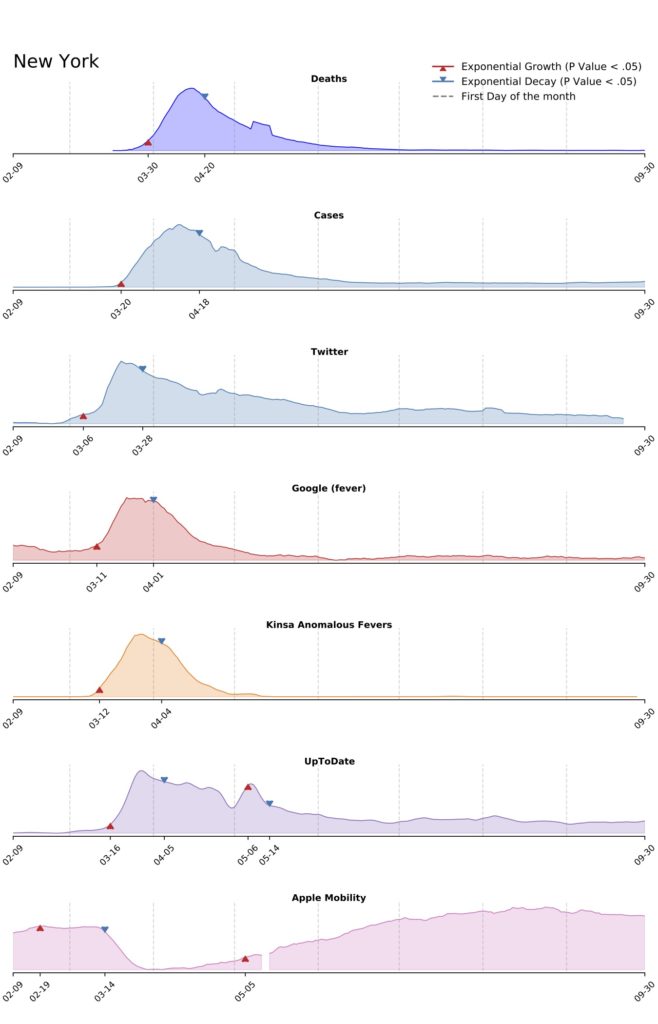

Santillana and colleagues analyzed Google search data, tweets, clinicians’ searches on UpToDate (a medical information platform), temperature data from “smart” thermometers, smartphone location data (an indicator of social distancing). They, too, looked back at COVID-19’s early days, from March through September 2020.

Telling search Google terms included “chest tightness,” “dry cough,” “loss of smell,” “anosmia” (the medical term for loss of smell), and “robitussin.” Telling tweets mentioned things like “panic buying,” “quarantine,” and “state of emergency.”

When combined, these data sources sounded a strong warning signal — fully two to three weeks before reported growth in COVID-19 in a community and three to four weeks before reported deaths.

“If multiple sources are raising red flags independently, that increases our confidence in the signal,” says Santillana, who directs CHIP’s Machine Intelligence Lab. “If we see a sharp increase in people searching for ‘anosmia,’ while doctors are searching for ‘low oxygenation,’ thermometer data are showing an excess of fevers, and people are tweeting that they’re feeling sick, then we know it’s likely that an outbreak is going on.”

Future pandemics predicted

These studies aren’t purely an academic exercise. Santillana is using the data to advise public health officials in Massachusetts about potential hotspots. Vaccine maker Johnson & Johnson is using it to identify counties with sufficient numbers of COVID-19 cases to do clinical trials. Santillana envisions the creation of an agency that could produce “weather forecasts” for disease outbreaks.

Experts agree that more outbreaks of new diseases are in our future. Trends like greater population density and deforestation are bringing humans in closer contact with other animal species that might pass along new pathogens. Zika, Ebola, and COVID-19 are recent examples. When the next unknown illness hits, our online searches could guide the public health system when it’s at its most vulnerable.

Get more answers about Boston Children’s response to COVID-19

Related Posts :

-

Five things to know before getting an online second opinion for your child

Whether you want to confirm your child’s diagnosis or treatment plan, another set of expert eyes can give you ...

-

No limitations: How Flora found answers for MOG antibody disease

Flora Ringler’s fifth birthday didn’t turn out as she had hoped. She and her family were vacationing in ...

-

Forecasting the future for childhood cancer survivors

Children are much more likely to survive cancer today than 50 years ago. Unfortunately, as adults, many of them develop cardiovascular ...

-

What orthopedic trauma surgeons wish more parents knew about lawnmower injuries

Summer is full of delights: lemonade, ice cream, and fresh-cut grass to name a few. Unfortunately, the warmer months can ...