From Toronto to Boston: Osteochondritis dissecans, hockey, and hope

Hockey is a fast and physical sport. Players need to think and act quickly as their team members, opponents, and the puck zip around the ice. Wherever the puck goes, high-speed collisions often follow.

Osteochondritis dissecans is a joint disorder in which a segment of bone and cartilage starts to separate from the rest of the bone as a result of repeated stress or trauma. The injury most commonly occurs in athletes between the ages of 10 and 20.

“It’s pretty intense,” says Grady Finch of Toronto, Ontario. “I enjoy that.”

Grady started playing hockey when he was 4. By the age of 9, he was playing in a AAA league, the highest level a player of his age could attain. Overall, he was in a great place until osteochondritis dissecans gave his hockey future a serious body check.

Knee pain and an unwelcome diagnosis

For Grady, the first sign of a problem was knee pain that grew worse over time. “It crept up slowly until it was clear he needed to see a doctor,” says Grady’s father, David. An MRI revealed he had osteochondritis dissecans in both knees.

The doctor who diagnosed him in Toronto told Grady he needed to avoid any activities that involved running or jumping so his knees could heal. “It affected all my sports,” Grady remembers, “the things I loved doing most.”

“Basically, they told him to stop being a 12-year-old boy,” adds David.

After a long and difficult year, Grady’s left knee locked up one day when he stood up from the couch. Instead of better, his knee seemed worse, and it would be five weeks before they could get an initial consult with an orthopedic surgeon in Toronto. The Finch family was tired of waiting.

In search of an osteochondritis dissecans specialist

Even before the setback with Grady’s left knee, David had been looking online for specialists with experience treating osteochondritis dissecans. He found a list of ROCK (Research in Osteochondritis of the Knee) doctors, which included three specialists at Boston Children’s Hospital. David sent an email to one of them, Dr. Benton Heyworth.

“I sent an email on Sunday night and Dr. Heyworth replied on Monday morning saying he could see us that week.” On Tuesday, Grady and David were in Boston for an in-person consultation.

When he reviewed Grady’s most recent MRI scans, Dr. Heyworth found that the right knee had healed on its own, but an area of cartilage in Grady’s left knee was too damaged to heal without surgery. “After a year of restricted activity, that was hard news to hear,” says David.

Exploratory surgery and good news

Less than two weeks later, in December 2019, Dr. Heyworth performed an arthroscopy. First, he made a small incision near Grady’s knee. Then he inserted a tiny camera through the incision so he could look inside the knee.

From this vantage point, he could see it would be possible to repair Grady’s knee with a procedure called OATS (osteochondral autologous transplantation surgery). The procedure involves taking healthy tissue from one part of the knee and using it to replace the injured bone and cartilage.

“OATS is not used to repair osteochondritis of the knee too frequently,” says Dr. Heyworth. “But when it can be, in my experience, it has excellent results because a patient’s own bone and cartilage will heal better than with other options.” The other options would have involved using donor cartilage to repair the knee or using some of Grady’s own cartilage to grow new cartilage. Either one would have required a second trip to the operating room — and more waiting.

The fact that Grady’s injury could be repaired on the same day as the arthroscopy was a long-awaited bit of good news for the family.

“My wife, Tamara, and I knew the procedure would be short if it was only exploratory,” says David. When the operation took several hours, they knew Dr. Heyworth was repairing Grady’s knee. “The level of care at Boston Children’s was so high,” he says. “We had complete confidence in the whole team.”

The long road back from osteochondritis dissecans

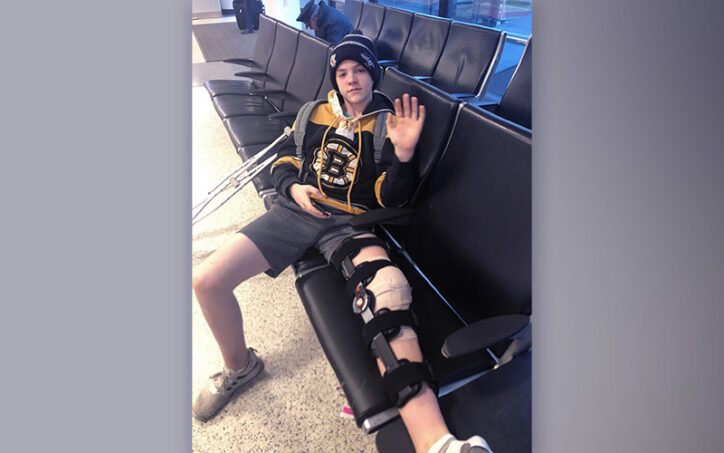

With the surgery behind him, Grady faced another 12 to 13 months of rehabilitation. COVID-19 further prolonged his time off the ice.

Finally, in September 2021, more than three years after his original diagnosis, Grady returned to the game he loved, playing once again on his AAA team. Having spent much of the past 18 months in the gym, he came back stronger and more determined than ever.

His hard work paid off in April 2022 when, at the age of 16, he was drafted by a team in the Ontario Hockey League. “There was a time when I did not think I’d be close to playing at this level,” says Grady. “It was definitely daunting not knowing how long I’d be out for or how well my knee would recover.”

“As a father, I’m obviously proud of his accomplishment,” says David. “But I’m most proud of how he dealt with the bumps of the past three years. Through dedication and hard work, he’s shown that it is possible to play sports at a high level post-surgery.”

When asked what advice he’d give other families facing osteochondritis dissecans, David recommends seeking care from an experienced specialist. “In hindsight, we waited a year when there was no chance Grady’s left knee would heal. Our experience shows why it’s important to get an opinion from an expert.”

Learn more about the Sports Medicine Division.

Related Posts :

-

Ryker's comeback from osteochondritis dissecans

When Ryker Casey takes the field, everything comes down to the strength of his legs and precision of his kick. ...

-

Always an athlete: Drew and Legg-Calve-Perthes disease

When he looks back on the diagnosis that forced him to stop playing sports entirely for more than a year, 11...

-

Sports medicine helps keep athletes in the game

Sports medicine specialist Dr. William Meehan sees a lot of sports injuries: everything from tennis elbow to concussions to anterior ...

-

After two ACL tears, a skier reconnects with her body and her sport

The memory remains vivid in Sophia’s mind. Racing down a slalom course at top speed, she hit a patch ...