Why do some children exposed to the coronavirus go on to develop MIS-C?

Most children exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus have few or no symptoms. But a small number become sick enough to go to the hospital. And a tiny handful develop a severe inflammatory illness called multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), often weeks after initial exposure to the virus. Why?

A team at Boston Children’s Hospital is using a cutting-edge genetics technology to try to get at this question.

“We’re looking for variations in the structure of DNA that make children susceptible to MIS-C,” says Catherine Brownstein, MPH, PhD, assistant director of the Molecular Genetics Core Facility, who is co-leading a new study with Alan Beggs, PhD, director of the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research.

MIS-C genetics: Genetic sequencing and beyond

The study builds on work already underway at Boston Children’s. The Children’s Rare Disease Cohort Initiative, led by David Williams, Piotr Sliz, and Shira Rockowitz, is providing blood samples. A team led by critical care physician Adrienne Randolph, MD, MSc, and immunologist Janet Chou, MD, has been sequencing children’s entire genome, identifying all the “letters” that make up our genetic code, or exome (sequencing a smaller group of genes that code for proteins).

These traditional methods can identify “spelling” changes in the genetic code. Another method, called chromosomal microarray analysis, can pick up duplicated or missing segments of DNA in our 23 chromosomes.

But there are other kinds of genetic changes that neither of these technologies can pick up.

“This new project takes the next step, looking at changes in the deeper structure of a person’s genome,” says Randolph. “These changes help could explain why some young individuals develop rare complications from COVID-19, or very severe illness.”

Imaging children’s DNA

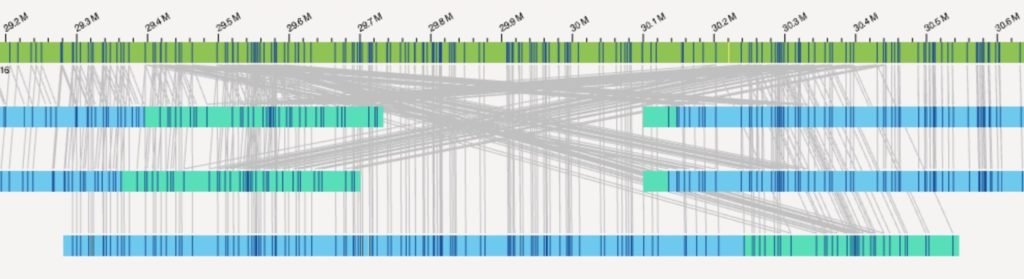

Brownstein and Beggs are using a sophisticated platform called Saphyr, provided by Bionano Genomics, to image and map the structure of the genome. Their plan is to analyze the DNA of children with MIS-C, children with severe COVID-19 but not MIS-C, and children with mild or asymptomatic infections. In all, they hope to enroll 50 children in each group, looking for hard-to-find differences in the chromosome structure.

“We have one of only two Saphyr machines on the East Coast,” says Brownstein. “Its unique power is its ability to identify structural variations that are too big for traditional DNA sequencing to detect, but too small for chromosomal microarray to pick up. Our hypothesis is that some of these variations might influence genes important for the development of MIS-C, or might interact with triggers in the environment.”

“In addition to finding deletions and duplications, the system can also identify chromosome rearrangements, like a piece of DNA that’s flipped around or moved to a different location on the chromosome,” adds Beggs.

Understanding immune differences

Randolph and Chou will lend their medical expertise to the project. Randolph’s research focuses on the immune system’s role in critical illness in children. As leader of the nationwide Overcoming COVID-19 study, she has been tracking the health, immune responses, and inflammatory responses of children with MIS-C. Chou, who directs Boston Children’s Primary Immunodeficiency Program and Immunogenomics Program, will provide input on how chromosomal changes affect genes involved with the immune response.

The research could also shed light on why some adults with COVID-19 develop life-threatening inflammation. The Boston Children’s team has joined the COVID-19 Host Genome Structural Variation Consortium, which is studying patients of all ages. They hope to compare their findings with those in up to 850 adult cases.

If Saphyr can crack the genetics behind susceptibility to MIS-C, its uses could potentially be expanded to other diseases. Ultimately, the hope is that the genetics will teach us more about the immune system and how to strengthen our defenses against a variety of threats.

Learn more about MIS-C research at Boston Children’s.

Related Posts :

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...

-

Thanks to Carter and his family, people are talking about spastic paraplegia

Nine-year-old Carter may be the most devoted — and popular — sports fan in his Connecticut town. “He loves all sports,” ...

-

No limitations: How Flora found answers for MOG antibody disease

Flora Ringler’s fifth birthday didn’t turn out as she had hoped. She and her family were vacationing in ...

-

Genetic causes of congenital diarrhea and enteropathy come into focus

Congenital diarrheas and enteropathies are rare and devastating for infants and children. Treatments have consisted mainly of fluid and nutritional ...