‘Huggable,’ a social robot for kids, eases hospital stress

Children confined to the hospital often feel lonely, bored, or scared, and must cope with pain and homesickness. They may not fully understand why they are there or what will happen next. Hours can feel like days.

That’s where a robotic teddy bear called Huggable could come in, suggests a new study published today in the journal Pediatrics. The study is one of the first to look at the role of social robots in an inpatient setting.

The emotional side of medicine

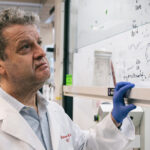

Deirdre Logan, PhD, director of psychological services at the Boston Children’s Hospital Pain Treatment Center, and Peter Weinstock, MD, PhD, director of the Boston Children’s Simulator Program (SIMPeds), worked with colleagues at Boston Children’s, MIT’s Media Lab and Northeastern University to design a social robot that could supplement care team interactions on inpatient units and help meet kids’ emotional needs.

“We wanted to offer kids one more way of helping them to feel OK where they are in what’s otherwise a really stressful experience,” Logan says.

The study also grew out of the SIMPeds team’s deep interest in understanding the emotional state of patients, families, and clinicians and how it impacts behavior, decision making and health outcomes.

“Huggable brings us a big step closer to being able to study that, and to measure and optimize emotion as perhaps the most important ‘vital sign’ in medicine,” Weinstock says.

Meet Huggable

Huggable is operated remotely, “voiced” by child life specialists through an implanted smartphone, using a child-like voice. Engineer-puppeteers move its arms, legs, head, and digitally animated eyes as the bear chats with children about their likes/dislikes, tells jokes, sings nursery rhymes and plays “I Spy.”

While you might think a child would see Huggable as fake or even creepy, the new study, involving hospitalized children ages 3 to 10, finds them highly receptive to visits.

The research team approached 68 children and ultimately randomized 54 of them to one of three 30-minute sessions: with Huggable, with a plush teddy bear that was held and “puppeteered” by a child-life staffer in the room, or with a tablet with interactive, remotely operated avatar of a bear resembling Huggable.

Social robot put to the test

All sessions were recorded on video, and children wore a bracelet called a Q Sensor that collected physiologic data: changes in skin conductance, temperature, and motion that may indicate arousal or stress.

Of the children who met Huggable, 93 percent said it was “fun,” and 92 percent expressed a desire to play with the bear again. Responses were similar with the tablet, but Huggable significantly outperformed the plush, non-robotic bear: 75 percent said that bear was fun, and 63 percent wanted to play with it again.

Children meeting Huggable, versus the plush bear, also reported happier feelings, and parents felt their children’s pain was lessened, across all medical conditions. Reviewing the video, the researchers tallied the most “joyful” utterances with Huggable, followed by the tablet and the plush bear.

Overall, the children who responded best to Huggable were 5 to 8 years old, verbal, and feeling well enough to engage. Findings reported earlier also show that children who interacted with the robot were more engaged and more physically active than children in the other groups.

The Q Sensor data suggested a modest positive effect in all three groups, but this small study was unable to find statistically significant differences between them.

Finding a place in the clinic

Introducing this technology into the hospital setting posed some challenges for the research team. There were some technical glitches with the robot in early phases of the study, and some children took off or wouldn’t wear their Q-sensor. Of the 18 children randomized to Huggable, five were excluded from analysis because of these issues or being afraid of the robot.

But those children who interacted with Huggable often displayed an emotional attachment or empathy, giving hugs and offering the bear pillow to rest on.

“The age group we studied, 3- to 10-year-olds, were at an ideal phase of development where they were truly able to connect with Huggable and to believe that he was there to provide comfort and support,” says Logan. “Children are particularly well matched to this type of technology due to their imaginative nature and ability to suspend disbelief. With further development, social robots like Huggable have real potential to help fill in pediatric patients’ emotional needs when caregivers and the healthcare team cannot be present.”

Overall, the study showed that with planning and problem-solving, social robots can integrate well into hospital care. Eventually, as artificial intelligence technology advances, the goal is for Huggable to function independently, expanding the reach of Child Life Services.

Huggable was highlighted in this 2015 New York Times video:

Logan was first author on the paper. Weinstock was senior author. Coauthors were Cynthia Breazeal, PhD, and Sooyeon Jeong, MS, of the MIT Media Lab; Matthew S. Goodwin, PhD, and James Heathers, PhD, of Northeastern University; Brianna O’Connell, CCLS, of SIMPeds and Child Life Services at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Duncan Smith-Freedman, BS, of SIMPeds.

Related Posts :

-

Promising advances in fetal therapy for vein of Galen malformation

In 2024, Megan Ingram* of California and her husband were preparing for the birth of their third child when a 34-week ...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...

-

A toast to BRD4: How acidity changes the immune response

It started with wine. Or more precisely, a conversation about it. "My colleagues and I were talking about how some ...

-

A safe, pain-specific anesthetic shows preclinical promise

All current local anesthetics block sensory signals — pain — but they also interrupt motor signals, which can be problematic. For example, ...