Accessing hemophilia care: A tale of two countries

When Miguel and Marco Antonio were born in the Philippines, they had a 50 percent chance of having hemophilia, as two of their uncles had the condition. “We were just crossing our fingers that they’d fall in the other 50 percent,” says Jojo, their father.

But when Miguel was taking his first steps as a baby, he fell and hit his head on a door. “I got a huge mark, and my forehead swelled,” Miguel recounts. “That’s how our parents knew.”

Marco, his fraternal twin, also was found to have hemophilia A, the most common form of hemophilia. Both boys had severe cases, with bleeding episodes virtually every week. Even minor exertions led to internal bleeding, causing swelling of their joints and tissues.

A driver would drive us to school and carry us up the stairs on his back.

Such bleeding can be controlled by infusing the clotting factor missing in the disease, factor VIII, several times a week. But the Antonios had trouble affording the medication, forcing them to ration it. The boys often received it only once per week, well below the dose recommended.

“The treatment is beyond the means of even middle class people in Philippines,” says Jojo. “One of the distributors in the Philippines closed down, so we had to source it from the U.S. I would fly to Manila to pick up the medication once a month.”

Hemophilia: Living with less

With no health insurance in the Philippines, the Antonios found it more affordable to hire nannies to limit the boys’ physical activity than to buy factor VIII. To avoid bleeding and its complications, the boys couldn’t play sports, run, or even walk distances longer than the length of a football field.

“We had a very sedentary lifestyle,” recalls Miguel. “A driver would drive us to school and carry us up the stairs on his back.”

Even so, the bleeding episodes continued.

“Even when we were in wheelchairs, we would get swelling from the impact of going over bumps,” says Miguel. “My swelling point was in my ankle and my knees — I have very weak knees.”

“I couldn’t straighten my left arm because of the bleeds,” says Marco.

In 2014, when the twins were 10, their mother Myrish was accepted into a master’s program at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, and the family decided to relocate to Boston. They soon connected with the Boston Hemophilia Center, where Dr. Stacy Croteau and her team at Boston Children’s Hospital began a comprehensive care and monitoring plan for the boys.

“We started them on standard-of-care treatment, including infusions of factor VIII concentrate multiple times per week,” says Croteau, medical director of Boston Children’s hemophilia treatment center. “Even at their young age, Miguel and Marco already had signs of joint injury. Starting prophylaxis as soon as possible helps to prevent or at least delay joint damage.”

“When we got our first supplies of factor VIII, that was the first time I was able to sleep without really worrying about Miggy and Marcky,” says Jojo. “Here we have health insurance, and could afford it.”

Hemophilia without fear

Now 16, Miguel and Marco have seen their lifestyle change dramatically. Both are 11th graders at the prestigious Boston Latin school. With regular treatment, a lot of the fear around physical activity has receded.

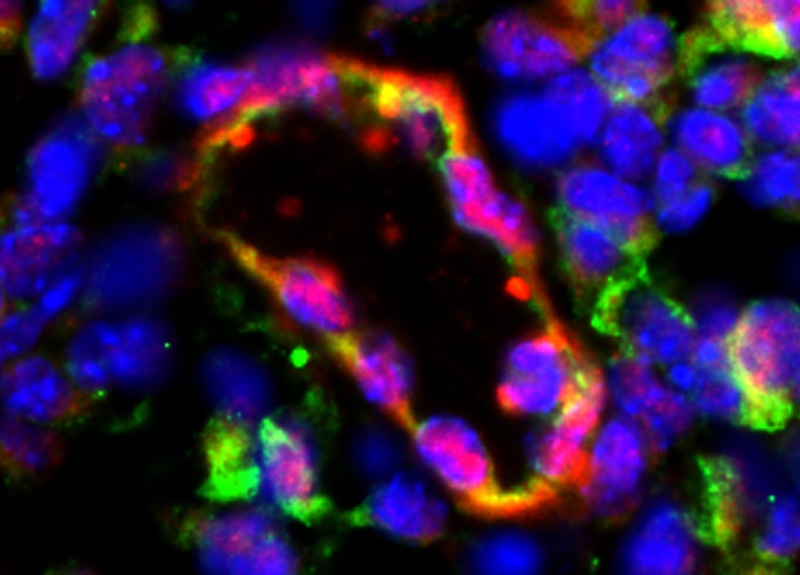

DONATING TO SCIENCE: Miguel and Marco are among seven patients who donated urine samples for a Boston Children’s study of a novel gene therapy treatment for hemophilia. The scientists culled and treated cells from the samples, inserting a healthy factor VIII gene. Implanted in mice, the cells formed blood vessels that secreted factor VIII into the circulation. The team now hopes to bring this approach to humans.

“Now, when I stub my toe on the door or hit my elbow, it doesn’t scare me,” says Miguel.

Contact sports are still out of the question, but Miguel is pursuing varsity rowing at Boston Latin, and Marco is captain of the fencing team. Croteau is fully on board: physical activity is important for their musculoskeletal and cardiovascular health, so long as it’s backed by a plan for preventing and managing bleeds.

“Miggy and Marcky are model hemophilia patients,” she says. “They are very adherent to their prophylaxis regimen, even though the regular intravenous infusions to maintain a safe factor VIII level are an enormous burden. Their dedication and determination have made them successful teenagers both academically and athletically.”

“We don’t find hemophilia to be a nuisance our lives,” says Marco. “In actuality, it has given us a different perspective on how to approach certain aspects of our lives. Hemophilia is a part of who we are, but we’re not defined by our illness.”

Giving back

Miguel and Marco are following the progress of a gene therapy safety trial for adults to see if the treatment proves safe. If so, they may seek to enter the trial when they turn 18. That study, led by Croteau at Boston Children’s, is using an engineered virus to deliver the factor VIII gene into liver cells.

The twins are very much aware of their good luck, knowing of other families in the Philippines whose children died for lack of access to treatment.

“The main thing is, how do we make medicines more accessible for kids in developing countries?” Marco says. “We’d like to help disadvantaged kids.”

With their sights set on college, Miguel is interested in pursuing economics and law, and is working with Boston City Hall on youth empowerment and disability issues. Marco is interested in biochemistry and genetics and did an internship last summer with Boston Children’s Division of Genetics and Genomics. That led to his current internship at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, which delves deep into disease genetics.

Both boys have also donated blood and urine samples for clinical and laboratory research on hemophilia A. (See sidebar above)

“We want to do everything we can to advance research in hemophilia,” says Miguel. “We’re very grateful and want to give it back in any way we can.”

Read more hemophilia stories.

Related Posts :

-

Promising advances in fetal therapy for vein of Galen malformation

In 2024, Megan Ingram* of California and her husband were preparing for the birth of their third child when a 34-week ...

-

The hidden burden of solitude: How social withdrawal influences the adolescent brain

Adolescence is a period of social reorientation: a shift from a world centered on parents and family to one shaped ...

-

A toast to BRD4: How acidity changes the immune response

It started with wine. Or more precisely, a conversation about it. "My colleagues and I were talking about how some ...

-

A unique marker for pericytes could help forge a new path for pulmonary hypertension care

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare condition that’s difficult to treat. The hallmarks of the disease — narrowing of ...