Gliomatosis cerebri: ‘As long as you keep going, you still have hope’

Anna Arabia, the only child of Kathy and Joe Arabia of North Adams, Massachusetts, was 13 when she was diagnosed with gliomatosis cerebri, a rare, rapidly-growing brain cancer. Unlike other tumors, gliomatosis cerebri does not form into lumps; instead it is threadlike, invading multiple lobes of the brain, making it impossible to remove surgically. Anna died on Feb. 14, 2013. She was 16 years old.

Anna’s story

Born in China and adopted into the Arabia family at 9 months old, Kathy describes Anna as “a fun, energetic girl who loved hanging out with her friends, loved computers and technology, and her iPhone.” She was a performer, a member of the drama club and the high school band. And she was a helper too, “able to turn even her most difficult challenges into ways to help others.”

A simple slip and fall, followed by a seizure, was the first indication something was wrong.

“She had no prior health problems,” says Kathy. “But that seizure brought us immediately to the emergency department and the start of this path we began on.”

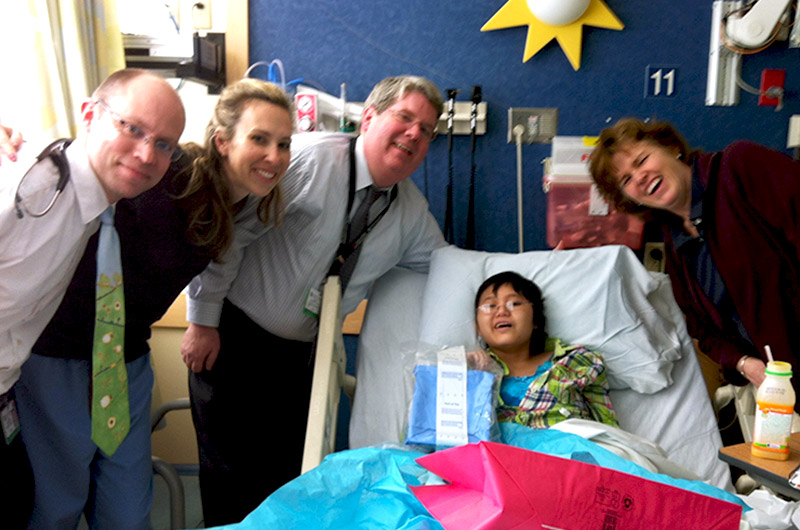

This path led them to the discovery of a brain tumor and a referral to Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, where Anna underwent surgery to have a portion of her tumor removed and biopsied.

“I was scared to death of what she had to go through,” says Kathy. “At the time, I did not know that for this type of tumor there are no survivors.”

Rather than focusing on the long-term prognosis, Kathy focused on each treatment that Anna bravely faced over the next three years — surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, investigational drugs and four clinical trials.

“As long as you keep going you still have hope,” says Kathy.

With each treatment cycle, there were periods where Anna stabilized, but ultimately the cancer found another way to continue growing. In November 2012, an MRI showed the tumor had spread to a much larger area of Anna’s brain. The Arabias made the difficult decision to discontinue treatment.

Driving gliomatosis cerebri research

In Anna’s memory, the Arabias created the AYJ Fund, to help drive critical research for gliomatosis cerebri. “I was shocked to learn there was no research being done,” Kathy says. “That was just unacceptable to us.”

The Arabias began connecting with other families through online groups and locating researchers with an interest in gliomatosis cerebri.

In 2015, momentum was gathering. Several researchers, with the support of family foundations from Europe and North America, including AYJ, organized the first Gliomatosis Cerebri Conference. Held at the Curie Institute in Paris, the conference brought together neuro-oncology researchers and physicians, including Katherine Warren, MD, formerly of the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, and currently clinical director for Pediatric Neuro-Oncology at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s.

“It was sort of a come to a consensus,” says Warren. “Is there enough interest in trying to study gliomatosis cerebri? Can we pool resources? Can we pool tumor samples? And, we decided, yes, we can.” The conference in Paris resulted in the creation of “GC Global,” an international community of foundations and families, all working together to support researchers involved in identifying effective treatments, and one day a cure, for gliomatosis cerebri.

Since then, GC Global has supported two more international conferences, the most recent held this past September in Barcelona, Spain.

“The same group of families have been behind this from the beginning,” says Warren. “And now, more families have joined us and are supporting our efforts and pushing research forward.”

Progress is slow but steady. More investigators have joined the initiative and one GC Global foundation member, the Rudy A. Menon Foundation, has funded a graduate student position, shared between the GC lab in London, the Filbin lab at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s, and the Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome, Italy. This student has begun to gather tissue samples from gliomatosis researchers around the globe. An additional multi-institutional GC research project will be awarded this spring by GC Global family foundations.

International Gliomatosis Cerebri Platform

To facilitate the collaboration already established through GC Global, Warren and another Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s pediatric oncologist, Tab Cooney, MD, launched the International Gliomatosis Cerebri Platform. This platform, run by an international network of experts studying and treating GC, is intended to drive and support translational discovery and clinical research, while serving as a center of communication for gliomatosis cerebri scientists. In addition to a messaging platform, there is a running list of information on tissue, cell lines, and models available to potential collaborators to make working together easier and more efficient.

‘We’re not there yet’

The collaboration between these leading research institutions and the focus on finding a cure gives families like the Arabias hope.

“We’re not there yet. We still have a lot of work left to do,” says Kathy. “But we know the research now being done at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s and these other research facilities will one day make a difference for other children with gliomatosis cerebri and their families.”

Learn more about the International Gliomatosis Cerebri Platform.

Related Posts :

-

Making genome sequencing a first-line test in rare disease

Children with rare diseases often undergo years of medical visits and genetic testing before they get a diagnosis. Over the ...

-

Boosting vaccines for the elderly with ‘hyperactivators’

As we age our immune systems start to flag, leaving us more susceptible to cancer and infections — and less responsive ...

-

In the genetics of congenital heart disease, noncoding DNA fills in some blanks

Researchers have been chipping away at the genetic causes of congenital heart disease (CHD) for a couple of decades. About 45 ...

-

The journey to a treatment for hereditary spastic paraplegia

In 2016, Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari, MD, PhD, a neurology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, met two little girls with spasticity and ...