Bringing genomics to community NICUs

About a year and a half ago, Robert Rothstein, MD, FAAP encountered a baby with a pattern of facial features and clinical findings that suggested a genetic syndrome. The available tests couldn’t pinpoint a diagnosis, and the family wanted a more definitive answer. So Rothstein and his colleagues transferred the newborn from Baystate Medical Center (Springfield, Mass.) to Boston Children’s Hospital — 90 miles away — for a more in-depth genetic workup.

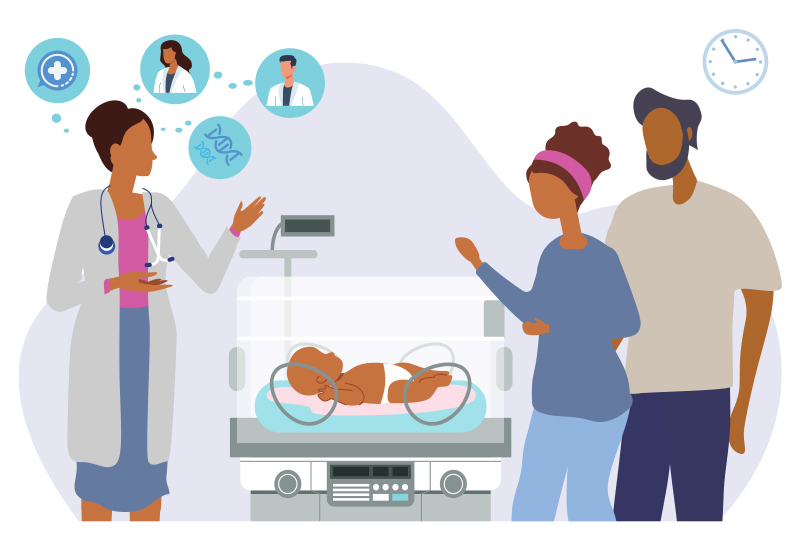

By the time the parents met with the Boston Children’s team to discuss their baby’s genetic diagnosis, they were anxious and mistrustful. The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) team in Boston suggested patching Rothstein into the family conferences and decision-making.

“I think my being there, even virtually, helped de-escalate the tension, because I had already established a relationship with the family,” says Rothstein, Baystate’s interim division chief of newborn medicine. “The value of having a familiar face involved in these difficult discussions was readily apparent.”

Pankaj Agrawal, MD, MMSc, who directs the Neonatal Genomics Program in Boston Children’s Division of Newborn Medicine, was also in the family conference. He too saw the value of involving the local neonatologist. But he wanted to go a step further — and avoid the need to transfer newborns to Boston Children’s for genetic evaluations at all.

Equity in genomics: Overcoming NICU barriers to access

Under a $5 million federal grant, Agrawal and colleagues Timothy Yu, MD, PhD at Boston Children’s and Margaret Parker, MD at Boston Medical Center are forming a Virtual Genome Center (VIGOR) for Infant Health. Through telemedicine, the project will bring advanced genomic services and education directly into Baystate’s NICU. Three NICUs in Boston, Worcester, Mass., and Camden, N.J. are also participating.

“Our goal is to empower community neonatologists and give them confidence in genomic testing so they won’t have to depend on specialized centers,” says Agrawal.

All four of the NICUs serve populations that are more than 40 percent Black or Hispanic — who have been underrepresented in genetic testing and research. Between them, the project aims to enroll 250 sick newborns with signs of genetic conditions, such as unexplained low muscle tone, seizures, metabolic disorders, immune deficiencies, disorders of sex development, or multiple congenital anomalies.

The local NICUs will first send the newborns’ blood samples to an outside DNA sequencing company. The company will then return the results to Boston Children’s. When genetic results are negative or inconclusive, or the interpretation unclear, the VIGOR team will re-analyze the data. When needed, specialists and rare disease experts at Boston Children’s will provide input.

“We will then create our own reports for the patient and share them with the treating team, explaining what the genetic findings mean and what can or cannot be done for the baby,” says Agrawal.

Virtual genetics education

In the early stages, VIGOR team members, including senior genetic counselor and project manager Jessica Douglas, MS, LGC, will be on hand virtually to help the local neonatologists disclose the genetic results to families.

That includes sharing the baby’s expected medical outcomes, counseling the family on having additional children, and, in some cases, recommending changes to care. For example, newborns identified as having a seizure disorder and a particular mutation on sequencing could receive a potentially more effective anti-seizure medication.

“We want to help local NICUs be comfortable with these kinds of disclosures and see if they can evolve into doing these things themselves,” Agrawal says.

That’s where the educational part of VIGOR comes in. In between virtual sessions about genomics and how to have conversations with families, local physicians can ask questions via VIGOR’s secure platform. Families can also use the platform to seek further information about their genetic findings, learn about studies relating to their child’s condition, and connect with support groups.

Exploring the impact of genomic medicine

VIGOR will follow each newborn’s case for six months to learn how families respond to receiving genetic information, whether they find it useful, and how having a genetic diagnosis impacts the family overall. (Boston Children’s has co-led similar research through the BabySeq project, which reached primarily healthy babies from predominantly white, higher-income families.) The team will also survey the local neonatologists and track the infants’ health outcomes. Eventually, Agrawal hopes to expand the program to more community NICUs.

Rothstein is enthusiastic about the future.

“We continue to have babies that stump us, because we don’t have as many tools in our toolbox to run these diagnostic tests,” he says. “Having an entire genetics team at Boston Children’s working in conjunction with our geneticist and neonatal team is a great opportunity to get expertise without having to transfer the baby — a big cost and stressor for the family. The patients can stay here with us and close to their homes and families.”

Learn more about the Neonatal Genomics Program

Related Posts :

-

Solving genetic mysteries – in the NICU and beyond

A growing number of children with suspected genetic disorders are having their complete exomes sequenced, since it’s now often ...

-

Solving neurodevelopmental mysteries, one gene, one child at a time

Suheil Day was born early, at 37 weeks. Aside from a slight head lag and mild muscle weakness, nothing seemed terribly ...

-

Newborn genetic screening for pediatric cancer risk could save lives

Numerous genetic mutations increase children’s risk for various cancers. When they are detected early, cancers can potentially be caught ...

-

A promising new antiseizure drug tailored to newborns

Neonatal seizures can lead to serious consequences, including significant cognitive and motor disabilities, lifelong epilepsy, and death. They are ...