Mapping cells to create targeted treatments for interstitial lung disease

John Kennedy, MD, MSc, remembers the relative simplicity of his first genetic mapping project. In a Harvard Medical School lab, he helped map a gene for the neurological disease mucolipidosis type IV in less than a year.

“I was fresh out of college. I thought with the global momentum of the Human Genome Project, we were going to quickly map every gene. We were going to know that this problem here causes this disease, for almost every disease. But it’s definitely more complicated than that.”

Kennedy recognized the challenges of mapping as he sought to find the genetic causes of childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD) as a Boston Children’s pulmonologist. Genome sequencing has helped solve some cases, but the genetic underpinnings of most chILD diseases are still unknown. One obstacle is that only a small number of children have chILD. Also, the diseases have diverse genetic causes, making it hard to establish patterns.

Still, Kennedy has reason to again be optimistic. He and other researchers are scaling up a successful Boston Children’s initiative to a national level: the Inflammatory chILD Cell Atlas, an open-source project funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative that will profile and characterize the molecular composition of single-cell populations in the inflammatory chILD samples of 100 patients. They have already classified 30 chILD cases, one of which led to a meaningful targeted treatment for a patient. They hope more new treatments are to come. “We can do this,” Kennedy says.

Advanced technology provides a clear picture

Many chILD diseases overlap and often look similar in their clinical presentations. “They kind of look the same when a patient’s health worsens,” Kennedy says. “When biopsies are taken, some of the pathologic findings look the same. Some of the blood markers also look the same.” And because the genetic causes of most chILD diseases are unidentified, treatments have to be broad in scope, limiting their efficacy.

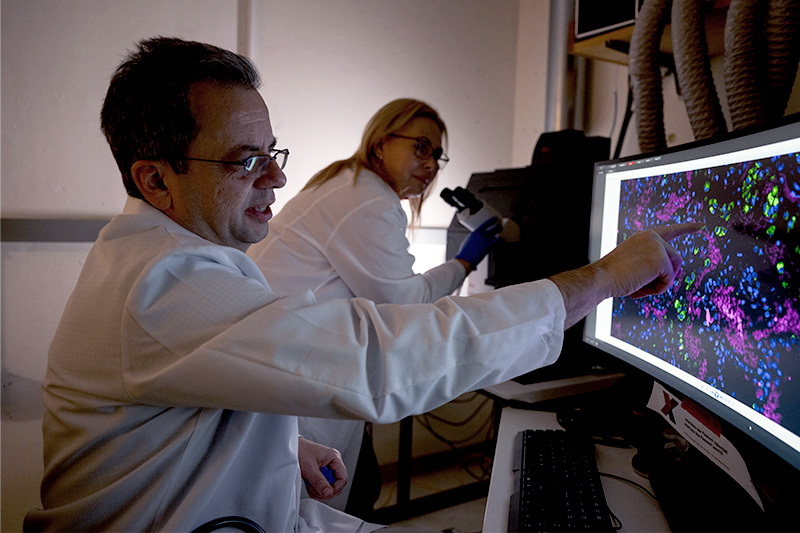

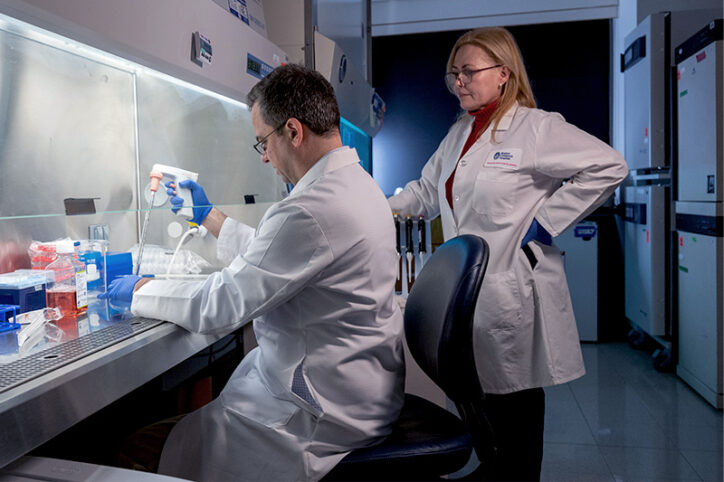

The Inflammatory chILD Cell Atlas team believes their approach can make a difference. Using advanced sequencing technology known as spatial transcriptomics, they are sequencing every nucleus from the lung tissue samples of 100 patients of diverse ancestry who have inflammatory chILD. The biopsies will be integrated with whole-exome sequence data to prioritize genes and map the molecular causes of undiagnosed cases.

The team wants to define disease-specific cell subpopulations and their related disease-specific genetic signatures. They hope to see how effectively pulmonary cells trigger the functioning of RNA, determinations that will be based on prior research of diseased lungs. Their research will form an open-source single-nucleus RNA-seq lung tissue atlas, from which clinicians around the world can gain insight about specific genetic patterns and the pathways of inflammatory chILD. From there, pulmonologists will hopefully be able to treat patients with targeted molecular therapies, Kennedy says.

Kennedy is the principal investigator of the study, working alongside Boston Children’s colleagues Benjamin Raby, MD, MPH, and Martha Fishman, MD; the University of North Carolina; and the Children’s Interstitial and Diffuse Lung Disease Foundation.

chILD Atlas has already helped a patient

Kennedy has already seen molecular mapping pay dividends. It helped him and his Boston Children’s colleagues define a new disease: progranulin-associated interstitial lung disease.

They determined a 14-year-old girl had the disease after sequencing her and her family’s biopsy samples. Their finding led to a change in the girl’s medication, which quadrupled her lung function, got her off oxygen therapy, and reversed her liver disease, allowing her to move back home to the Middle East after living in Boston for four years to be close to Boston Children’s.

Most medicines that currently treat chILD are “blunt” anti-inflammatories that shut down all pathways and have side effects such as the stunting of growth and a susceptibility to bacterial infections, Kennedy says. But once the chILD Atlas helps researchers and clinicians see a detailed level of molecular classification for those lung diseases, “we can start pulling in medicines that pulmonologists normally don’t use but are used in rheumatology and oncology — targeted and effective molecular therapeutics.”

“During my career, we’ve gotten better at targeting cell types in asthma, and we’ve done an amazing job targeting the exact channel in cystic fibrosis. But pulmonary medicine is still far behind in treating interstitial lung diseases. I hope this atlas helps.”

Learn more about the Interstitial Lung Disease and Pulmonary Genetics programs.

Related Posts :

-

Cell therapy for lung disease? Proof-of-concept study shows promise

Many serious pulmonary diseases, including genetic lung diseases, lack an effective treatment other than the most extreme: lung transplant. A ...

-

Mermaid Caitlyn and her mer-doctor face interstitial lung disease

Our daughter Caitlyn's first year-and-a-half of life was a puzzle. She was getting sicker and sicker and no one near ...

-

Ductus arteriosus stenting could help severely ill infants with pulmonary arterial hypertension

Treatment for infants who have severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is sometimes limited. Because they haven’t physically ...

-

Study seeks to identify household triggers for chronic lung disease in children

Home is where the heart is, but it’s also where air pollutants, allergens, and other irritants can make breathing ...