An advance for drug-eluting contact lenses: Delivery to the back of the eye

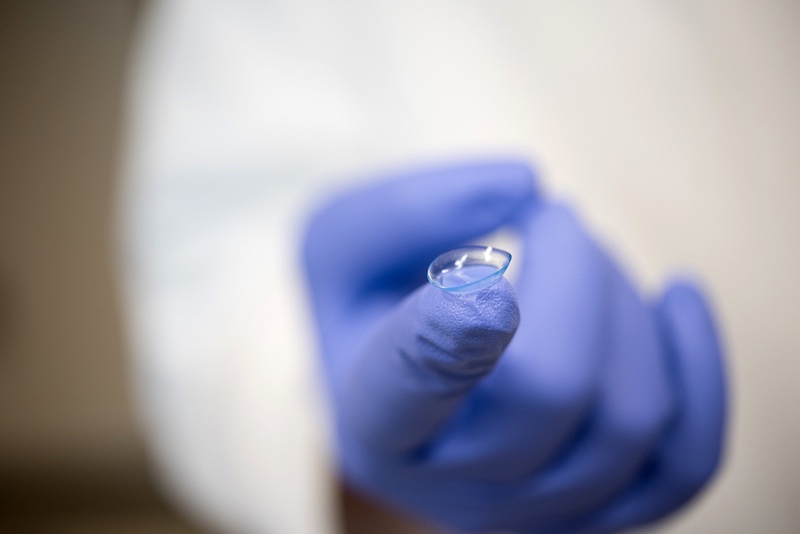

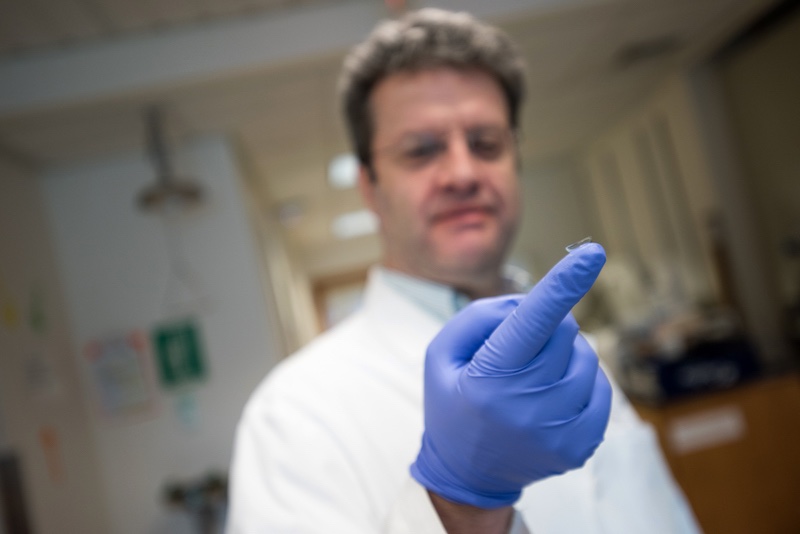

Drug-eluting contact lenses, which gradually release drugs into the eye, offer a promising alternative to daily eye drops, which can be unpleasant and hard for patients to properly administer. In a 2016 pre-clinical study of glaucoma, the engineered lenses lowered eye pressure at least as well as daily eye drops.

New work from Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Boston Children’s Hospital extends these findings to the harder-to-reach back of the eye, particularly diseases of the retina. Currently, most retinal diseases require eye injections and implants that carry potential side effects, some of them serious. Moreover, nearly 1 in 4 patients given eye injections don’t come back, due to a fear of needles in their eyes.

“Though there are drugs that are effective for these conditions, it is hard to get them to the retinal tissues in an non-invasive way,” says Joseph B. Ciolino, MD, the Henry Freeman Allen Cornea Scholar at Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

Ciolino co-led the new study, published in Biomaterials, with Daniel S. Kohane, MD, PhD, director of the Laboratory for Drug Delivery and Biomaterials at Boston Children’s. It tested contact lenses dispensing dexamethasone, a steroid used to treat inflammatory eye diseases.

Promising preclinical findings

In preclinical animal models of uveitis and macular edema — two forms of eye inflammation — the lenses safely provided sustained drug delivery to the retina for one week. In fact, to the team’s surprise, the lenses provided 200 times the concentration levels of hourly eyedrops, and were as effective as eye injections in preventing retinal damage.

“We had previously shown that our design for drug-eluting contact lenses could provide sustained release of substantial amounts of drug, over extended periods, to the anterior parts of the eye,” says Kohane. “The question then became whether this approach could be used to treat diseases of the back of the eye — the retina and adjacent structures. We now know we can.”

Within one year, the team hopes to launch clinical trials to study the effectiveness of the lens in human patients, Ciolino says.

Amy E. Ross and Lokendrakumar Bengani, both of Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Boston Children’s, were co-first authors on the study. Ciolino and Kohane are inventors on a patent related to this work filed by Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Boston Children’s Hospital.

Related Posts :

-

New research sheds light on the genetic roots of amblyopia

For decades, amblyopia has been considered a disorder primarily caused by abnormal visual experiences early in life. But new research ...

-

Modeling urinary tract disorders on a chip: Zohreh Izadifar

When a new tissue sample arrives from the Department of Urology, the Boston Children’s Hospital lab of Zohreh Izadifar, ...

-

Guided by her own experience, one mom navigates Stickler syndrome with her children

Aimee is more than just Mum to three-year-old Arwen and one-year-old Cedric; she’s their guide to navigating Stickler syndrome, ...

-

Genetic variants are found in two types of strabismus, sparking hope for future treatment

Determining how genetics contribute to common forms of strabismus has been a challenge for researchers. Small discoveries are ...