Dr. Dennis Spencer: The world needs more diverse doctors

If you ask Dr. Dennis Spencer, he’ll tell you one of the best things about practicing medicine is the opportunity to work directly with people and communities. As a physician in Boston Children’s Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, he diagnoses and treats children with digestive disorders and educates patients and families about preventive measures they can take at home.

As a Black doctor, he also expands children’s idea of who they can grow up to be. “I love that I can be a role model for my patients,” he says. “I take that responsibility seriously because of the historic lack of doctors from underserved communities, like the one I grew up in.”

Why diversity matters in medicine

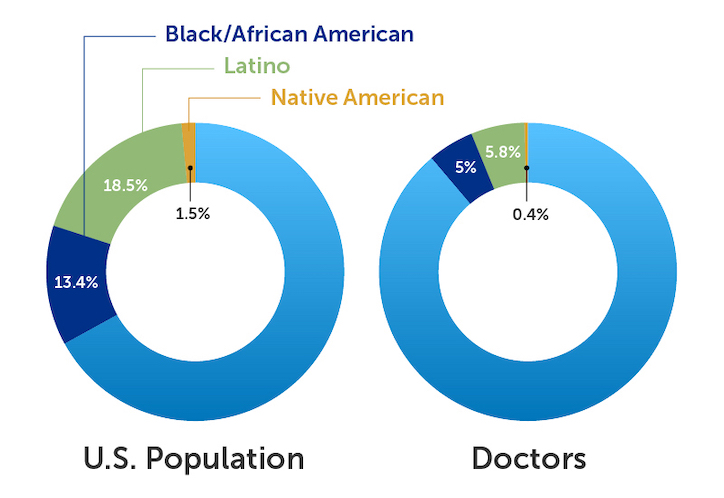

As early as fifth grade, many children of color have absorbed the message that they shouldn’t expect to succeed as doctors because of their race. Unfortunately, due to the low number of Black, Latino, and Native American doctors in the U.S., children from these groups have little evidence to put such self-doubts into question.

The lack of diverse doctors is bad for patients’ health. People who feel a connection with their doctors tend to have stronger patient-doctor relationships and better overall health. Those who can’t relate to their doctors, or whose doctors don’t understand their lives and circumstances, are less likely to receive the care they need when they need it.

By sharing his story, Dr. Spencer is part of a national effort to shift medicine toward greater equity and inclusion.

A non-traditional path into medicine

Throughout his childhood in Baltimore, Dr. Spencer was never treated by a Black doctor. Nor did he start out at the top of his class. “I had a significant speech impediment,” he says. “My parents were constantly questioned about whether I was smart.” His speech challenges affected his performance in school, and he was assigned an individualized education plan (IEP).

Supporting diverse medical students

Getting into medical school is a long and often complicated journey. Without guidance, many nontraditional students get lost or discouraged. To increase their chance of success, Dr. Spencer co-founded a nonprofit called Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians. The organization helps diverse medical students and residents explore academic medicine as a career option and offers guidance and mentorship for those who choose to embark on that path.

None of this stopped his parents — or him — from setting their expectations high. The Spencer household was stocked with books about Black achievement and the family made frequent visits to the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum in Baltimore. “My parents did things like this to make sure my siblings and I had a sense of self and pride of our community.”

His parents’ efforts paid off. Dr. Spencer became inspired by Black scientists such as Dr. Ernest Everett Just, Percy Julian, and George Washington Carver. By high school, he was doing lab research. He entered Morehouse College planning to be a microbiologist but soon became aware of a broader opportunity. As a “physician-scientist,” he would be able to treat patients while also researching diseases and possible new treatments.

Having role models helped him believe that he could succeed. “I met a number of physician-scientists who allowed me to see that this could be a career path and the steps I needed to take to achieve that goal.”

Medical school: Opportunity and challenges

Dr. Spencer describes medical school as an amazing opportunity to learn about human health and disease. Unfortunately, it’s also a time when many Black and brown students feel singled out and isolated. “I always try to prepare diverse students for the fact that they may face frustrations and stressors that many of their classmates will not experience,” he says.

Like many other medical students of color, Dr. Spencer held himself to an unattainable standard of perfection in an ongoing effort to prove he belonged alongside his mostly white classmates. “Imposter syndrome (the feeling that you don’t measure up) is pervasive in medical school, particularly when you are one of the only students from your background.”

I tell all the young people I mentor now that I will be upset if I find out that they are struggling and not reaching out.”

Dr. Dennis Spencer

Looking back now, he says that several mentors and allies were essential to his success in medical school. “I tell all the young people I mentor now that I will be upset if I find out they are struggling and not reaching out.” He wants them to succeed for their own sakes — and for the future of medicine.

“We need diversity in medical school in order to learn from each other’s lived experiences and to ground future doctors with a deeper understanding of patients from a broad range of backgrounds.”

The next generation of doctors

Today, Dr. Spencer is a doctor, researcher, and faculty chair of the Graduate Medical Education Committee’s Diversity, Recruitment, and Retention subcommittee at Boston Children’s. In that role, he and his colleagues are working to increase the number of diverse residents and fellows in the hospital’s many training programs, and to ensure a supportive learning environment. He is also a faculty advisor for the Harvard Medical School’s Office of Recruitment and Multicultural Affairs.

He has a strong resume, but that’s not what he hopes tomorrow’s medical students focus on.

“I want young people to know this career path is not only for perfect people,” he says. “I had a challenging start with my speech impediment, an IEP, and general lack of familiarity with the seemingly hidden rules of how to be successful in this field. I had naysayers who told me not to reach too high. They may have been trying to save me from the disappointment they likely anticipated as inevitable. It was thanks to my parents’ unwavering faith in me that I didn’t listen to these dissenting voices.”

Dr. Spencer has this message for those who could become the next generation of doctors:

“If you are an aspiring physician of color, the field of medicine NEEDS YOU. Your future patients need you. If you believe medicine excites you, I want YOU to consider this career path!”

Learn more about initiatives in health equity, diversity, and inclusion at Boston Children’s and the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

Related Posts :

-

With a dose of health equity, brachial plexus study enrolls more patients

What drives a parent to say yes or no to enrolling their child in research? When a surprisingly high percent ...

-

Addressing inequities in asthma by focusing on children’s environments

Asthma strikes children in low-income urban areas especially hard, more often sending them to the hospital. For more than 20 years, ...

-

Standing up to microaggressions: A hospital-wide training

How can a large, teaching hospital address racial bias in the midst of a pandemic? This question came to a ...

-

Team spirit: How working with an allergy psychologist got Amber back to cheering

A bubbly high schooler with lots of friends and a passion for competitive cheerleading: On the surface, Amber’s life ...