Could plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients help others?

As new cases of COVID-19 mount daily, treatment revolves around supportive therapy to reduce symptoms, meaning there are no treatments shown to slow down or kill the SARS-CoV-2 virus. One new idea actually isn’t so new: transfusing blood plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients into patients currently sick with the disease. Last week, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave approval for the use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma in seriously ill patients.

Why could convalescent plasma have some benefit?

To learn more about the potential benefits and risks of using convalescent COVID-19 plasma in today’s pandemic, we spoke with Richard Malley, MD, senior physician in infectious diseases at Boston Children’s Hospital.

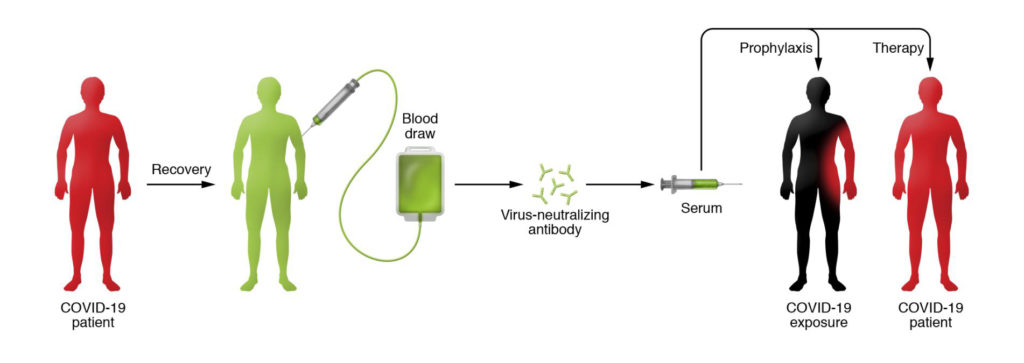

After an individual becomes infected with a virus, antibodies develop in the blood against it. Some of these antibodies have neutralizing properties that can inhibit or kill the virus. The hope is that the neutralizing antibodies in the plasma from one patient will hopefully reduce the symptoms and risk of death in infected patients with the same virus.

What are the proven benefits in earlier disease outbreaks?

The first recorded instance of using convalescent plasma was in the late 1800s. Since that time, plasma therapy was used effectively to prevent and treat many bacterial infections (like diphtheria, pneumococcus, meningococcus) and some viral infections (like measles, mumps, influenza). In the 1918 influenza pandemic, plasma therapy was associated with a 21 percent reduction in risk of death in several studies.

More recently, convalescent plasma was used to treat outbreaks of viral diseases including polio, measles, mumps, and influenza. It was used with some success in the 2009-2010 H1N1 influenza outbreak and in the 2013 West African Ebola epidemic.

Pertinent to today’s outbreak, convalescent plasma was used in two earlier coronavirus pandemics with high mortality rates: the 2003 SARS and the 2012 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreaks. In a SARS trial of 80 patients, administration of convalescent plasma within 14 days of onset of illness was associated with a better outcome compared with treatment later in the course of their illness. This suggests that convalescent plasma would be more likely to be effective early after infection or appearance of symptoms.

Is there any experience with plasma therapy in the current COVID-19 epidemic?

A recent report from JAMA describes five critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients in China with COVID-19 who received convalescent plasma. These patients’ clinical improvement was associated with receipt of the plasma but no conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of the approach.

What are the considerations or risks of therapeutic convalescent plasma?

Given past experiences, the high mortality rate in critically ill patients with COVID-19, and the absence to date of any proven effective therapies, the use of convalescent COVID-19 plasma is a very reasonable approach to consider. However, this therapy must be done with the utmost care, a difficult task in the midst of a pandemic.

The FDA emphasizes the need for clinical trials: "Although promising, convalescent plasma has not been shown to be effective in every disease studied. It is therefore important to determine through clinical trials, before routinely administering convalescent plasma to patients with COVID-19, that it is safe and effective to do so.”

In response to the national emergency, the National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project was established on March 24, 2020 to provide information to:

Health care providers who are considering using convalescent plasma to treat patients, either outside of a trial or in the context of a randomized trial

Patients who have recovered from COVID-19 infection and are willing to donate plasma

Patients with any stage of COVID-19 (or their families) who are considering this treatment

Any member of the public interested in learning more about convalescent plasma use currently and in the past (see section on key papers)

From earlier experience, and in the very few case reports with COVID-19, it seems that plasma therapy is most likely to work when given early in the disease. It is possible that, as the disease progresses, the patient’s own inflammatory response to the virus is causing much of the damage and viral suppression by antibody may no longer be as useful.

It is also important to recognize that plasma therapy can cause a severe lung disease called transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and could also be associated with the transmission of other blood-borne pathogens. For these reasons, any use of plasma therapy for COVID-19 should be performed in a highly controlled setting.

How can we minimize the risks?

One strategy is to identify sera with high concentrations of neutralizing antibodies capable of killing the virus. It is likely that not all convalescent patients develop high levels of neutralizing antibodies. Developing tests that can measure the neutralizing capacity of a donor’s plasma is critically important.

There is a need to move fast but not so fast as to forego the usual scientific and ethical considerations. It means organizing ourselves so that safeguards are in place to prevent injury to these sick patients as much as possible; to define the plasma to be used and who is going to receive it; that trials be designed carefully so you can evaluate whether the treatment is showing any efficacy early on. ” Richard Malley, MD

The second step is to carefully choose the test population. The ideal group includes people who are sick, but not so sick that you may not be able to see if the therapy had any beneficial effect. Also, you may want to avoid giving it to people who are at highest risk of TRALI or other harmful effects from the therapy itself. The best patient group might be those with moderate-severe illness but who are not critically ill nor on ventilators.

Third, you want to be sure of course that the trials are done in a way that allows evaluation of the efficacy of the intervention. Plasma therapy is an expensive and complex procedure, requiring plasma collection by a regulated collection facility. We want to make sure that we determine as quickly as possible if it is beneficial.

Read more COVID-19 information from Boston Children’s.

Related Posts :

-

No limitations: How Flora found answers for MOG antibody disease

Flora Ringler’s fifth birthday didn’t turn out as she had hoped. She and her family were vacationing in ...

-

What orthopedic trauma surgeons wish more parents knew about lawnmower injuries

Summer is full of delights: lemonade, ice cream, and fresh-cut grass to name a few. Unfortunately, the warmer months can ...

-

Partnering diet and intestinal microbes to protect against GI disease

Despite being an everyday necessity, nutrition is something of a black box. We know that many plant-based foods are good ...

-

‘They never stopped trying to figure out what was happening’: RyennAnne’s encephalitis journey

When 5-year-old RyennAnne Hurst developed a bad sore throat last summer, her doctor thought she might have strep and prescribed ...